By Linda Batchelor

The Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck was the forerunner of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution and William Broad of Falmouth was one of the earliest recipients of the Institution’s Gold Medal for a rescue at sea. This month’s Bartlett Blog stems from some wider research undertaken by the Library into the Broad family of Falmouth and concerns the background to the rescue, the rescuer, and the award from the Royal National Institution.

The Wreck of the Larch

On January 10th 1828 the Ship News of ‘The Standard’ newspaper reported the loss of the brig Larch, ‘driven ashore at Falmouth on a voyage from Newfoundland to Poole in Dorset’. In June 1829 William Broad of Falmouth was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck for his part in the rescue of the crew and passengers from the wreck of the Larch.

The 150 ton brig was heading for Poole with a cargo of fish, blubber and furs. There was a crew of 11 under the master, Collingwood, and there were also three passengers, a Mr Pearce and his two daughters returning to England. The voyage had taken 21 days from Newfoundland and on 7 January, sailing in stormy and freezing winter weather off the coast of Cornwall, the master decided to run for haven in the port of Falmouth. The conditions were extremely difficult and in attempting to enter the harbour the brig was driven close to the opposite shore and after dragging her anchor hoisted distress signals. These signals were seen by William Broad who began the attempt at rescue.

William Broad

At the beginning of the 19th century William established a home and a business in Falmouth. Initially trading as William Broad & Co. the company soon became well known as shipping agents and merchants in the sea borne trade, importing a variety of goods including wines and spirits. In 1811 William Broad & Co were appointed as one of the very first (probably the first) agents and marine surveyors for Lloyds who were dominant in shipping insurance.

William was born in 1772 and raised in the vicinity of Penzance where a number of Broads were established in trade and as ship owners. William was educated at Truro Grammar School and his early career at sea began in command of modest merchant vessels working out of Penzance. Gradually he obtained command of larger vessels sailing out of Truro and Falmouth which were mainly involved in trade with the Mediterranean and the Middle East. His last commands as master of such ships were the Pelican and the Phoenix of Truro. His reputation for seamanship, reliability and for his honourable and good conduct grew, so that when he quitted the sea in 1808, it was with ‘the highest testimonials’ and his business in Falmouth flourished. A few years before the rescue from the Larch in November 1816 he had rendered assistance to the Mary and Dorothy in distress near Falmouth during a storm by ferrying replacement cables and an anchor to the ship. His obituary published in 1853 by ‘The West Briton’ newspaper noted, ‘He was remarkable for extreme kindliness of heart, and for great physical energy, which prompted him on all occasions to acts of daring humanity.’ It was one such act which led to his award of the Gold Medal from the Institution.

The Spackman of Penzance under the command of Captain William Broad 1795. Private Collection.

The Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck

On 4 March 1824 a public meeting of 30 prominent men of the day took place at the London Tavern in Bishopgate. The meeting was called by Sir William Hillary and included figures such as Thomas Wilson MP for the City of London, William Wilberforce and George Manby. Sir William had published a pamphlet in 1823 with the proposal he had long championed of establishing a national body for rescue at sea and the purpose of the 1824 meeting was to implement that proposal. The result was the founding of the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck with a mission ‘to rescue wrecked persons from drowning on the coasts of the United Kingdom by every available means, both direct and indirect.’ Within two months of the foundation the National Institution became the Royal National Institution after receiving the patronage of King George IV. In October 1854 the name changed again to the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, the RNLI.

Sir William Hillary, a former royal equerry and soldier, had moved to live in the Isle of Man at Fort Anne near Douglas in 1808. He was appalled by the losses brought about by the many shipwrecks in the seas around the island and this prompted his proposals for a national rescue service. In the early 19th century there was an annual average of 1,800 shipwrecks around the coast of Britain. Soon after arriving in the Isle of Man, convinced of the need for a co-ordinated rescue service, he had approached the Admiralty with his plan without success. He continued to campaign and lobby for support from the government, other bodies and members of society but it was not until 1824 that the measure became a reality. Today Sir William Hillary is recognized as the founder of the national lifeboat service and his profile is engraved on the obverse of gallantry medals awarded to members of that service.

One of the earliest accounts of a rescue service is recorded in Formby in 1776 and in 1785 the first patented lifeboat was designed by Lionel Lukin, a London coachbuilder with an interest in improving the safety of boats. The following year he was commissioned to use his design for an ‘unimmergible’ boat to convert a coble, a traditional open fishing boat, for rescue purposes at Bamburgh. In 1789 a competition was sponsored by merchants in South Shields to design a lifeboat and both William Wouldhave and boatbuilder Henry Greathead submitted designs. Ultimately Greathead constructed a rowed lifeboat using features of both Lukin’s and Wouldhave’s design which was called ‘The Original’ and within 20 years there were 30 in operation. Early lifeboats were rowing or sailing vessels with steam power introduced in 1890 and the first motor powered vessel in 1905. The number of lifeboat stations increased steadily until today when there are 238 stations throughout England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

The Awards for Gallantry

The granting of awards for gallantry by the Institution was made a priority and by June 1824 the decision had been made to award medals in gold and silver for rescues from the sea. The first Gold Medal award was made for a rescue that year to Captain Charles Fremantle, then serving with the Coast Guard Service at Lymington. He swam out through heavy seas with a shoreline attached to give assistance to the Swedish brig Carl Jean stranded near Christchurch.

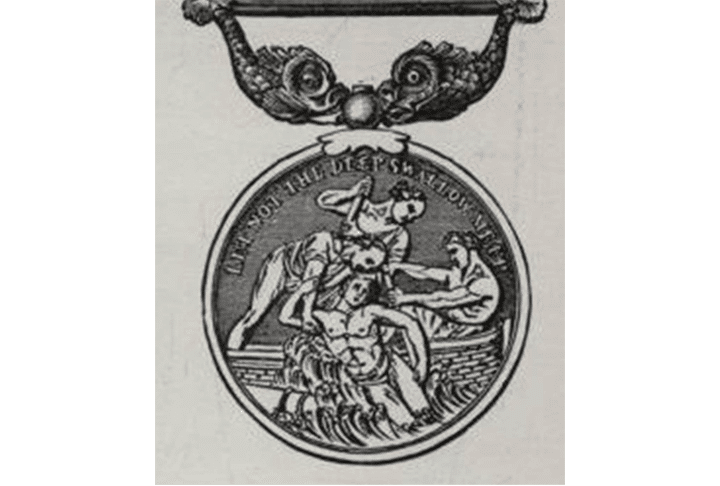

Originally the award in gold or silver (bronze was added in 1917) was called a medallion and came with no means of suspension. Later a ring suspension and a ribbon were added and since 1852 the suspension has taken the form of two dolphins. The dies for the medal were cut by William Wyon who was Assistant and then Chief Engraver for the Royal Mint from 1816 until 1857. He became known for his talent, artistic skill and prolific output in engraved portraiture, and he was elected to the Royal Academy as an associate in 1831 and as a member in 1838.

On the obverse of the first medals was a representation of the unlaureated head of George IV which Wyon based on a portrait bust of the King by Sir Francis Chantry. A sketch by Henry Howard R.A. was the basis of the design for the reverse showing the rescue of a figure from the sea by three others. The image of the rescuer lifting the figure from the sea is a portrait of William Wyon himself. The design is surrounded by a quotation from Psalm 69, ‘Let not the deep swallow me up’. Today, although the obverse of the medal now bears the image of Sir William Hillary the reverse remains as the original design.

Stories of the Lifeboats’, Frank Mundell, The Sunday School Union, 1894. Design of the Gold Medal with the original reverse image and the later suspension in the form of two dolphins.

These gallantry medals are now awarded for the work of lifeboat crews but in the early years of the Institution they were also awarded to others, including William Broad.

The Rescue from the Larch

On 7 January there was a heavy gale blowing as the Larch attempted to reach the safety of Falmouth harbour and the crew were hampered by the bitterly cold weather which had frozen the rigging and ropes on the ship. The gale drove the brig towards the headland at Trefusis opposite Falmouth and close to the village of Flushing. The crew were unsuccessful in attempting to deploy the anchor and the brig was being driven towards rocks near the New Quay pier in Flushing. To those on board it must have seemed there was little chance of survival when they put out distress signals.

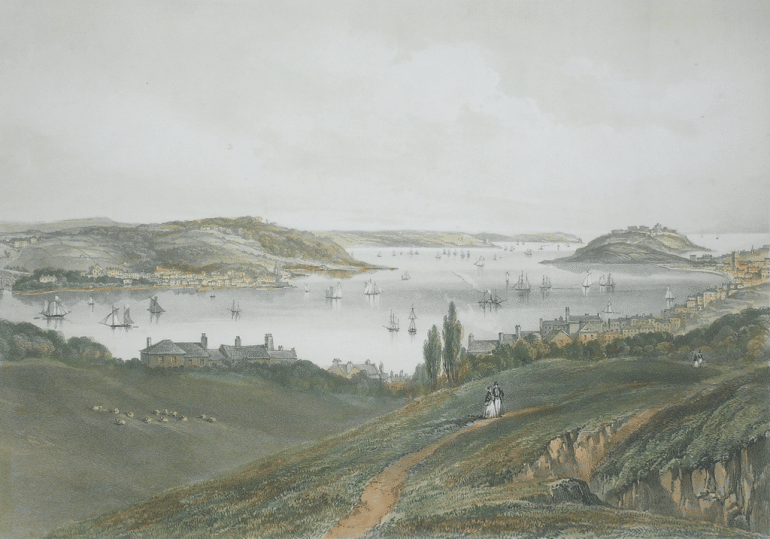

Captain Broad was in Falmouth on the other side of the harbour but realised the life-threatening danger of the situation and it was totally within character that, despite the treacherous conditions, he should attempt a rescue. William and a harbour pilot rowed a six oared open gig across the harbour and he was able to board the stricken vessel. He worked tirelessly to try to save the brig cutting away cables and assisting the crew, now all in great physical distress. The onset of darkness hampered the efforts but the inhabitants of Flushing provided light to help by setting fire to furze and tar barrels on the hill. With more assistance it was possible to run a cable from the ship to the shore and the crew and passengers were finally brought to safety that way although all but the Master were suffering from frostbite.

Falmouth Harbour and Flushing from the time of William Broad’s rescue of the brig Larch. Falmouth Art Gallery. Flushing and Trefusis Headland can be seen to the left of the picture across the harbour from Falmouth.

In early 1829 ‘The New Monthly Magazine’ reported that William Broad, Agent of Lloyds at Falmouth, had been awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck. The Committee had awarded the medal as ‘testimony of their approbation of the humane and spirited conduct’ of Captain William Broad in boarding the sinking Larch and achieving the rescue of the passengers and crew.

Read more about William Broad

For more about William Broad visit NMMC’s online journal Maritime Views and see the article Broad & Sons of Falmouth – A Merchant Firm and Family.

The Bartlett Blog

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. For Those in Peril on the Sea was written by Linda Batchelor.

The Bartlett Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.