By Linda Batchelor

This blog is dedicated to the rescue work of HM Coastguard on their 200th anniversary. It highlights two major developments in the history of shipwrecks prompted by the wreck of HMS Anson near Helston in December 1807 which resulted in great loss of life. One was the development by Henry Trengrouse of his rocket powered method of rescue and the other was the law in regard to the burial of bodies of those lost to the sea.

A Shipwreck

Loe Bar, situated on the Cornish coast between Porthleven and Gunwalloe, is a broad shingle bar and behind the Bar lies Loe Pool, Cornwall’s largest freshwater lake. The Bar is exposed on the seaward side to the heavy Atlantic tides and this stretch of coast has often proved treacherous. It was at Loe Bar that HMS Anson, a Royal Navy frigate came to grief in a ferocious storm and was wrecked on 29 December 1807 with enormous loss of life.

A view of Loe Bar and Loe Pool in calm weather.

HMS Anson was built in Plymouth and launched by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, in 1781 as a ship of the line with 64 guns. As time went by the design of fighting ships evolved and HMS Anson became less effective so that in 1794 the ship was the subject of a razee. This was a process of being cut down with the removal of the forecastle and the quarterdeck and a reduction of the ship to a frigate of 44 guns.

As a frigate the ship continued to have a distinguished history in the Royal Navy and was refitted during the Napoleonic Wars but although stronger, as a frigate she was not easy to handle in strong winds and was ‘no dainty sailor’. In 1807 HMS Anson was part of the Channel Fleet assisting in the blockade of Brest and was under the command of Captain George Lydiard. The ship arrived in Falmouth from blockading duty for re-provisioning on 11 December. She left again on 24 December with more than 260 persons on board, towed out of Falmouth Roads by her own boats to rejoin the blockade at Black Rocks off Brest.

HMS Anson. A detail from a painting by Thomas Luny (1759 – 1837).

48 hours later off Ushant the weather became increasingly inclement and Captain Lydiard decided to return to Falmouth. During the return voyage the storm became violent making progress and navigation difficult. Gripped by the increasing storm they mistook their position in relation to the Lizard, became embayed in Mounts Bay and being driven towards the shore were forced to anchor off Loe Bar. Initially the main anchor held the ship, but the storm intensified throughout the night of 28 December and at 4am the anchor cable snapped to be followed at 8am by the loss of the sheet anchor. The ship was at the mercy of wind, rain and ferocious seas, close to being overwhelmed and in the conditions the crew were unable to launch boats for the shore. Captain Lydiard decided that the only hope of saving lives was to beach the vessel but the attempt failed and the impact with the dense and heavy shingle of the Bar swung her broadside to the beach and the ship was overwhelmed by the pounding waves. The mainmast fell ‘by the board’ onto the sands and provided a means of escape for some but many were swept away from the deck, including the Captain, and others drowned below.

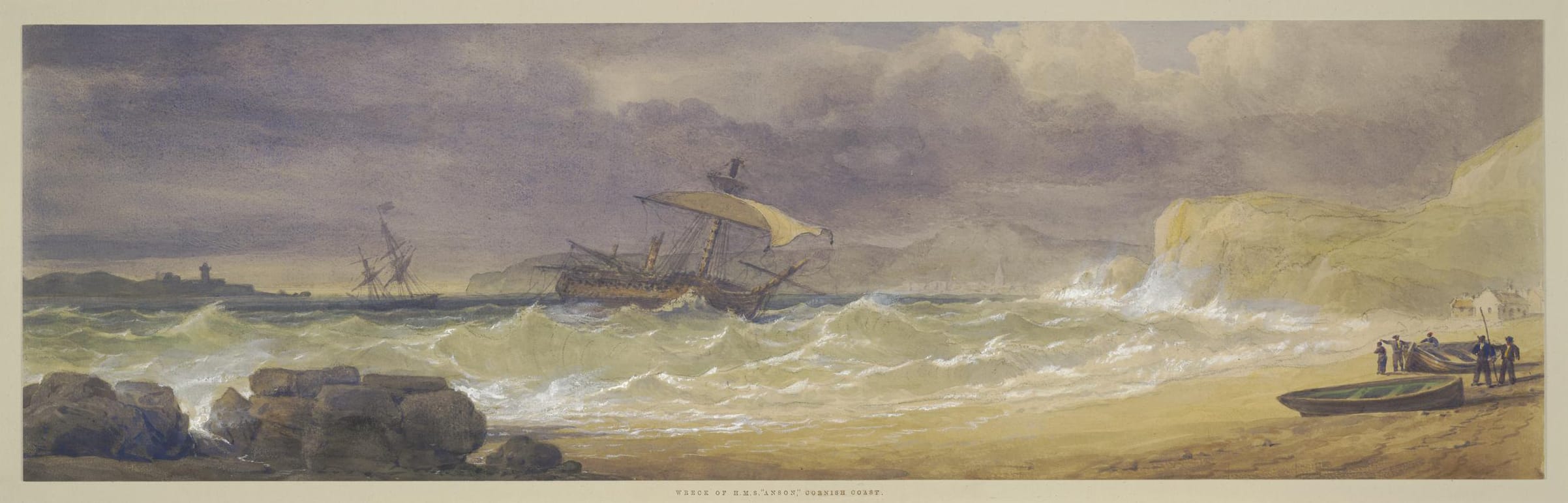

Untitled (Wreck of HMS Anson on the Bar of Loe Pool Cornwall), John Christian Schetky, The British Museum.

Hundreds of people from the nearby town of Helston and the surrounding area watched from the shore throughout the day and although there were some attempts a full-scale rescue was impossible given the conditions. About 2pm the ship went to pieces and by 3pm there was nothing left. Survivors were taken to Helston and the bodies began to come ashore. The body of Captain Lydiard was recovered on 1 January and was buried the next day in Falmouth with full military honours although the records show that in February his body was returned home to his widow and reburied in St Bartholomew’s Church in Hazelmere in Surrey. The numbers of those lost in the wreck vary but estimates are that between 90 to 150 are thought to have drowned. The Sherborne Mercury (11 January 1808) reported that a Court Martial was held in Plymouth on 7 January which heard ‘the melancholy recital of the cause which led to the shipwreck’ and the court unanimously acquitted the officers and crew of any liability for the loss.

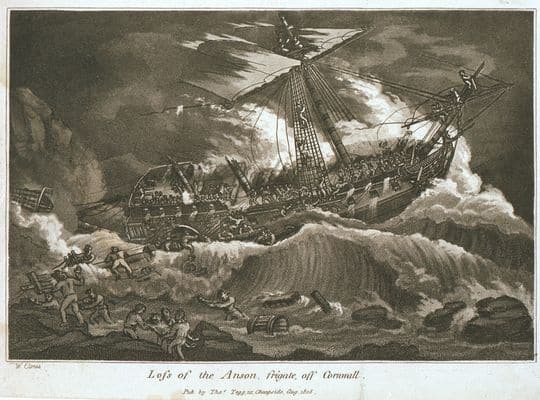

The Loss of the Anson frigate off Cornwall published 1808, William Elmes. Wikimedia Commons.

Rockets

Henry Trengrouse of Helston was amongst the many watchers on the shore at the wreck. He was a witness to the traumatic events and was especially struck by the inability of those on shore to reach those in need of rescue. The experience led Henry to design his rocket powered rescue system and the development of the bosun’s chair or breeches buoy.

Henry was born in Helston in 1772, the son of a Helston family, was educated at Helston Grammar School and lived there all his life. He became a cabinet maker but devoted much of his attention to the development of his life saving invention. Although his system was widely adopted and was a method of saving many lives Trengrouse received virtually no financial benefit and he died penniless in 1854.

Henry Trengrouse. Portrait by John Opie. Helston Museum.

His system was based on the use of a rocket to secure a line between a ship and the shore to enable rescue. Rockets were used as a form of artillery in the early 19th century and several ideas for line throwing were developed by artillery officers prompted by witnessing shipwrecks. In 1782 Sergeant Bell of the Royal Artillery had witnessed the sinking of HMS Royal George off Portsmouth. In 1791 he submitted his idea to the Society of Arts of launching a line from a ship propelled by a shell but although he received an award of 50 guineas from the Society the idea was not developed. Captain George Manby, Barrack Master at Great Yarmouth, experienced in artillery and the use of mortars, witnessed the loss of HMS Snipe at Gorleston south of Great Yarmouth in 1807. As a result, he developed the Manby Mortar the following year to launch a line from the shore to ships in distress. Manby received the Gold Medal of the Society and demonstrated his invention to representatives of the army and navy. The device was officially adopted in 1814 and a series of mortar stations were set up around the coast.

Trengrouse developed his rocket device independently in the same year of 1808 as Manby. However, it was not until 1818 that he was finally invited to demonstrate his apparatus to the Admiralty. The Committee appointed to consider the idea reported that, “Mr Trengrouse’s mode appears to be the best that has been suggested for the purpose of saving lives from shipwreck”. They recommended its adoption as did the Elder Brethern of Trinity House who stated that “no vessel should be without it”. His invention was recognised further with the award of the Silver Medal and 30 guineas from the Society of Arts. The Tsar of Russia invited Trengrouse to Russia to implement the device there but he refused the invitation on the grounds that he felt the invention should go to the British government first. Initially the government committed their support to Trengrouse and ordered 20 sets of the device. However they decided that further sets should be constructed by the Ordnance Department and instead awarded Trengrouse £50 in compensation for the loss of a future contract.

The apparatus became widely adopted both on land and on ships at sea and it became standard equipment for the coastguard service and for the RNLI. The rocket was easily fired using an adapted musket and the gradual acceleration of the rocket meant that there was less chance of line breakage on launch, which happened more with line launched by mortar. Unlike the mortar which required a land station the rocket system could also be used from ship to shore and had a superior range. It was lighter, easily portable in a small wooden chest and was less costly. Both the Manby and the Trengrouse systems could haul people from a wreck along a hawser with the Manby system using a cradle whilst Trengrouse used a seat. The seat was called a bosun’s chair by Trengrouse and this developed into the breeches buoy equipment. In later years modifications were made by others but the basic idea and design remained and, together with the lifeboat, the rocket apparatus became most important in rescues at sea. As his monument in St Michael’s churchyard in Helston acknowledges the invention by Trengrouse of his rocket apparatus “whereby many thousand of lives have been saved”.

A Change in the Law

Another result of the sinking of HMS Anson was the passing of the Burial of Drowned Persons Act in 1808. Until this date it was customary to bury unclaimed bodies of those drowned at sea in unconsecrated ground near to where they came ashore. They were buried on clifftops or above the tide line without shrouds or coffins and without markers.

The practice was widespread in coastal communities but the often unceremonious and sometimes dilatory disposal of bodies in this way began to attract adverse public opinion. This was the case with the multiple loss of lives at the sinking of HMS Anson. Although the body of the Captain was buried at Falmouth with full military honours the bodies of the vast majority of those drowned were unclaimed and were “buried hereabout” behind Loe Bar.

Many in Helston and the surrounds who had witnessed the wreck were shocked by the burial situation. Thomas Grylls, a Helston lawyer, drafted what became known as Grylls Act, requiring that such bodies should be laid properly to rest in the nearest consecrated ground. John Hearle Tremayne of Heligan, Member of Parliament for Cornwall, sponsored the measure through Parliament and it gained widespread public support so that within a year of the disaster the legislation was passed and the Burial of Drowned Persons Act came into force.

The Anson Monument at Loe Bar. Photograph South West Coastal Path – a photo tour.

Remembering

National Maritime Museum Cornwall

The Coastguard 200 exhibition opened in February 2022 and tells the story of the Coastguard and explores its role as one of the UK’s emergency services.

NMMC has a programme of schools workshops for Key Stage 1 including ‘Wreck and Rescue’ where students can discover the story of Henry Trengrouse’s invention of the rocket apparatus and the breeches buoy and take part in a recreation of a rocket and breeches buoy rescue.

In Helston

Henry Trengrouse is commemorated in the churchyard of St Michaels Church in Helston and in various ways in the town.

The Helston Museum has various exhibits about the life of Henry Trengrouse, the development of his rocket apparatus and a collection of rockets and lifesaving equipment. They also have a schools programme with a Key Stage 1 workshop about Henry Trengrouse.

There is a large cannon from HMS Anson at the entrance to Helston Museum which was salvaged off Loe Bar in 1964 by divers from Naval Air Command Sub-Aqua Club at RNAS Culdrose.

At Loe Bar

The Anson Monument erected in 1949 is situated south of Loe Bar.

The Bartlett Blog

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. A Shipwreck, Rockets and a Change in the Law was written by Linda Batchelor.

The Bartlett Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.