By Linda Batchelor

On January 10th 1815 The Western Luminary newspaper reported that ‘Captain William Broad, agent and surveyor to Lloyds at Falmouth has published a diary of winds and weather’. Captain Broad had settled to business as a ship agent in Falmouth after a distinguished career at sea and was still closely involved with seafaring, in publishing his weather diary he was joining with others in Cornwall who had been collecting weather information over a considerable number of years.

In the previous century the Reverend William Borlase, rector of Ludgvan in West Cornwall, a Fellow of the Royal Society, had published papers with the Society from the 1750s to the 1770s which had included a number on the Cornish weather. Other collectors of weather information in Cornwall during the 1700s were Mr Gregor of Trewarthenick near Tregony and Mr James of Redruth. During the 19th century Lovell Squire kept daily records between 1835 and 1856 from his house in Falmouth which recorded in tabulated form maximum temperatures, wind direction, quantity of rainfall and barometer heights.

It is not surprising that in Cornwall, a county with close maritime connections, there was an early interest in aspects of weather and the burgeoning of meteorological science. The county was important in shipping, fishing, trading and mining. It saw the early forms of industrialization and was a cradle of invention and scientific developments. The Cornwall Literary and Philosophical Institution, based in Truro, was formed in 1818 and renamed in 1821 the Royal Institution of Cornwall, to foster and promote excellence in science and art.

The Falmouth Connection

At the time Falmouth was one of the foremost ports in England and the home, since 1688, of the Falmouth Packet Service with its major mail and shipping routes to the Mediterranean, to North and South America and the Caribbean, all reliant on waves and weather. Although Falmouth was geographically isolated and had not come into being as a town until early in the 1600s it soon became a cosmopolitan port town, thriving both practically and intellectually which continued throughout ensuing years. A major development in the town in the nineteenth century was the founding in 1833 of a society ‘to promote the useful fine arts, to encourage industry, and to elicit ingenuity of a community distinguished for its mechanical skill’. This was the Cornwall, later, the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, the RCPS.

The idea was inspired by two teenaged sisters, aged seventeen and thirteen, Anna Maria and Caroline Fox. They were members of the Quaker Fox family who were prominent in Falmouth. The family were intellectually curious and embraced and encouraged artistic and scientific developments. The family firm was the Shipping agents of G C Fox & Co. They were also joint owners of Perran Foundry and were involved in mining, railways and other areas of Cornish industry. Robert Were Fox, the father of Anna Maria and Caroline, as well as being a senior member of the firm was a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was a natural philosopher, a geologist and an inventor, most notably of the Fox’s Dipping Needle used for magnetic observations.

The Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society building in the centre of Falmouth.

The family frequently entertained some of the interesting visitors to Falmouth including Captain Fitzroy of the Beagle who dined with them when his ship arrived in Falmouth in 1836. In his Journal, Barclay Fox, Robert ’s son and brother to Anna Maria and Caroline, described the Captain as having ‘just returned from a five years’ voyage of discovery about the Southern regions’, where he had been accompanied by the young Charles Darwin. During the visit Fitzroy discussed his voyage and his interest and observations on meteorology with the family. He was fascinated to learn about Robert’s invention of the Dipping Needle and Barclay noted that next day ‘Capt.f. (sic) breakfasted here and reports he was not able to sleep from the philosophical excitement of last evening. He and father were engaged in comparing observations with their respective instruments in the field all morning’.

This visit brought together some of those who were developing an early interest in the science of meteorology and who were to be important in its subsequent development. The Polytechnic Society collected weather data from early in its history as did the Royal Institution of Cornwall. Other institutions and individuals throughout the country followed suit and interest in meteorology grew steadily. In April 1850 the British, later the Royal Meteorological Society was founded as ‘a society the objects of which should be the advancement and extension of meteorological science by determining the laws of climate and meteorological phenomena in general’.

The Board of Trade’s Meteorological Department and Robert Fitzroy

The Board of Trade established a Meteorological Department in 1854. There was a developing international drive to improve knowledge and understanding of maritime meteorology and the department was set up as a service to mariners to improve the safety of life and property at sea. Admiral Francis Beaufort, the Admiralty Hydrographer of the Navy and inventor of the Beaufort Wind Force Scale, recommended that Robert Fitzroy be appointed as its chief. Fitzroy had developed his interest in meteorology as a surveyor and hydrographer in the Royal Navy and had gained fame as captain of the Beagle. He retired from active naval service in 1850 and the following year was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society on the recommendation of thirteen Fellows including Charles Darwin.

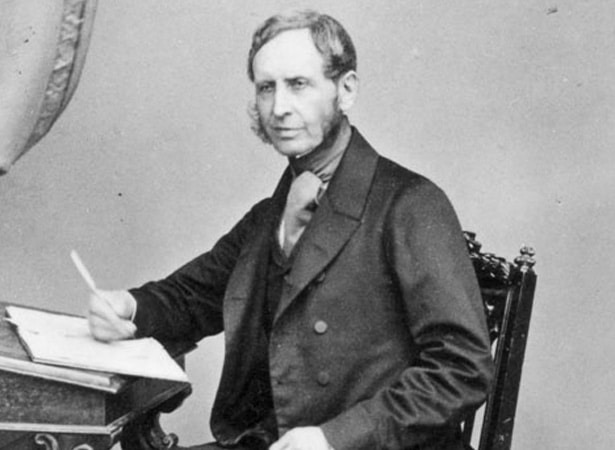

Robert Fitzroy circa 1860. The Alexander Turnbull Library NZ.

As head of the Meteorological Department Fitzroy worked to improve the scientific study of weather through the use of synoptic forecasting and developing the observation network to make such information more publicly available. He championed the maintenance of scientific weather reporting, produced detailed reports and charts and developed daily weather predictions which he called ‘forecasts’.

All these measures gained in importance after the Royal Charter gale which struck the country on the 25/26 October 1859. The storm began in the Bay of Biscay and tracked north from Cornwall to the Yorkshire coast bringing hurricane winds of force 12 and more than 133 ships and 800 lives were lost. A huge public impact was made by the sinking of one of those ships, the Royal Charter. It was one of the fastest and largest of the emigrant ships, which sank on the last part of a voyage from Melbourne to Liverpool with the loss of over 450 lives. The need to develop weather warnings for mariners was obvious. Fitzroy organized for barometers to be fixed in prominent positions at every port, in Falmouth it was sited near the Customs House, to alert mariners to weather conditions. A storm warning service was developed for harbours by early 1861 using a system of hoisted cones and cylinders. Fitzroy also established fifteen land stations to send daily weather reports to the department transmitted by telegraph and which allowed for the publication of the first shipping and land based forecasts.

However, despite these advances and the public popularity for weather forecasting, there was constant criticism from some in the scientific community who did not believe it was possible to predict the weather and doubted many of Fitzroy’s methods. Fitzroy’s health, physical and mental, suffered and he was frequently absent from his office. On 30 April 1865 he took his own life. His methods were carried on by his deputy Thomas Henry Babbington but in 1866 Parliament took the opportunity to reorganise the work of the Meteorological Office and pass some areas of work over to the Royal Society.

The Establishment of Land Meteorological Stations

The Royal Society established a Committee to consider ocean and land meteorology and proposed the establishment of three orders of land station (first, second and third) for the collection of data. Of the seven first order stations, Kew, the observatory of the British Association, was adopted as the central meteorological station which was to provide the pattern for the other such stations at Aberdeen, Glasgow, Stonyhurst, Armagh, Valentia and Falmouth. These stations were each to be equipped with a range of self-recording instruments to collect meteorological data and to be staffed by a superintendent or observer.

In Falmouth the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society (RCPS) had been collecting weather data since the 1830s and with a well established interest in scientific meteorology it was a natural choice for the Society to oversee the establishment and operation of the new Observatory.

The Observatory Tower 1867

An observatory tower was proposed and a site on Bowling Green Hill in the town, high above the harbour, was chosen and approved by Balfour Stewart the Director of Kew Observatory. As the building had to be suitable for the observation and measurement of weather data stipulations to the build were made by Kew. Building of the tower commenced in September 1867 and was completed in December of the same year. The land was secured by Mr Roberts, a builder and a member of the Polytechnic Society, who also undertook the expense of the building work. On completion Roberts granted the trustees of the Society a lease on the property of twenty one years at an annual rent of £60.

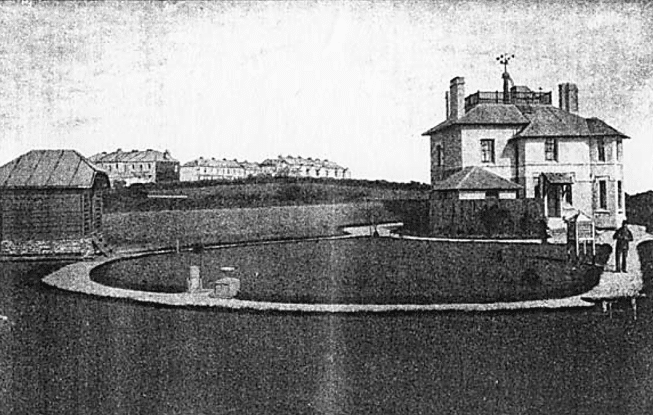

The Observatory Tower in Falmouth.

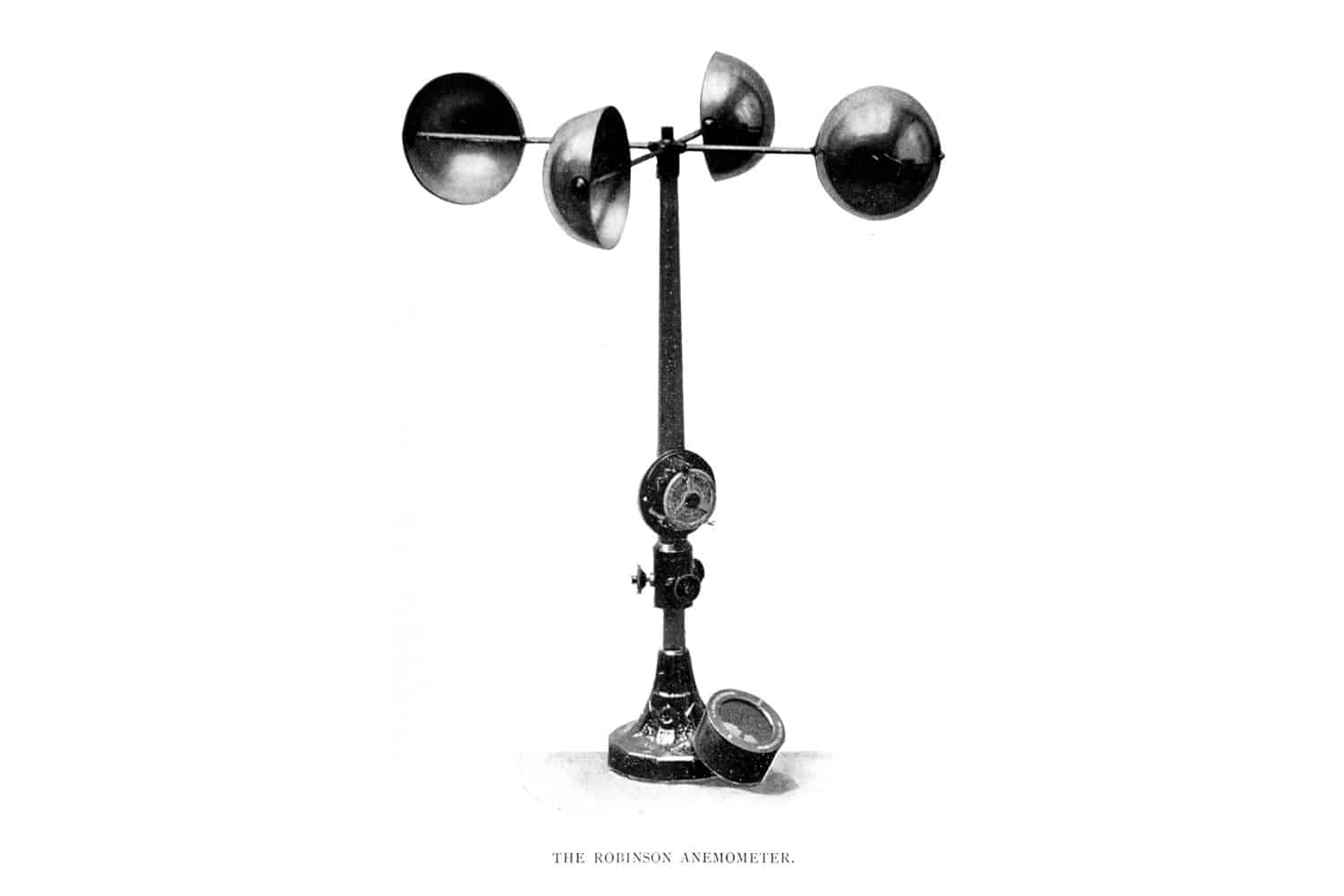

An annual grant of £250 was made to the Society by the government for the operation and staffing of the Falmouth Observatory. The Observatory was equipped with a range of scientific instruments for recording various weather observations and measurements. These included a barograph for atmospheric pressure, a thermograph for air temperature and evaporation and a Robinson anemometer for wind direction and velocity. There was also a Beckley rain gauge, a bright sunshine recorder and photographic equipment.

The Observatory was initially staffed by an Observer and in 1869 an Assistant Observer was also appointed. The duties of these two members of staff were overseen by the Meteorological Committee of the RCPS and the Meteorological Office. A detailed timetable of work was set out including collection tasks, equipment maintenance, photographic production and the preparation of various reports, tables and summaries for weekly, monthly or yearly publication. An annual inspection visit and report was made by the Observatory Inspector from Kew, George Whipple.

Lovell Squire was appointed as the Observer on the opening of the Observatory. Squire was a well known figure who had lived in Falmouth since 1834. He was born in Huntingdonshire in 1809 of a Quaker family and as a young man had taught at the York (later Bootham) School where he had introduced the pupils to the study of Natural History. He had moved to Falmouth as tutor to the sons of the Quaker Stevens family and by 1839 had set up and advertised a ’School for Friends children’ in the town where the teaching included ‘lectures on various branches of Natural Philosophy, given weekly in the winter months’. He was closely associated with the Fox family and was an early member of the Polytechnic Society where he gave lectures on scientific subjects. He took a close interest in the Meteorology Committee of the Society and kept daily weather records from his house in Falmouth. The school closed in 1849 after which he became the tutor to Barclay Fox’s sons. He left Falmouth in 1864 but returned when he was appointed as the Observer in 1867 at a salary of £100 per annum. He was joined by Edward Kitto from Breage near Helston as the Assistant Observer. His salary was only partly covered by the grant for the Observatory and therefore he was also appointed as Assistant Secretary to the Society.

The house in Kimberley Place, Falmouth where Lovell Squire ran his school.

The work of the Observatory generally progressed well over the years and established a good reputation. Observations and recordings were conducted as required and inspections were reported positively. Several expansion schemes regarding data collection were undertaken and various successes were gained towards the advancement of meteorological science. However, there were also some problems with the existing establishment. There were problems with the building such as damp, with the acquisition, positioning and sometimes damage of equipment and over time the site became ‘confined ‘. There were also some personnel problems between Lovell Squire and the Society regarding his contract and conditions. These eventually led to his resignation and retirement as Observer and Edward Kitto took over the post, assisted for a time by his wife Angelina Kitto.

The Fate of the Falmouth Observatory in the Balance

In 1883 the Royal Society’s Meteorological Council undertook a review of the role and the cost of the seven first order stations. As a result of the review the Council decided that some would have their financial support withdrawn which could mean closure or they could be demoted to second order volunteer stations. Although the Falmouth site was good geographically the position was confined and hampered the collection of data.

The fate of the Falmouth station hung in the balance and the RCPS immediately mobilised considerable forces to support the continuation of a first order station in the town. Arguments were put and representations were made to the Royal Society Meteorological Council by prominent national and local figures, peers and MPs, scientific experts and academics. The RCPS efforts was rewarded in November 1883 with a guarantee that the grant would be continued for the next five years if the Society agreed to a new Observatory building. Also there would be a further grant of £300 towards a new building on a better site.

The New Observatory 1885

The Society responded at once and a suitable site was identified at a high point in the town at the junction of Western Terrace and Killigrew Street. The freehold land was purchased from Lord Kimberley for £310 and the Society raised the further cost of the build by a well supported public appeal. The foundation stone was laid in a grand public manner in August 1884 by the President of the RCPS Lord Mount Edgecumbe and the building was completed in the spring of the following year. The site was more open with grounds attached and the building itself differed completely from the Tower. It was a large detached villa with seven observation rooms and private living quarters. Edward Kitto retained his position as the Superintendent Observer and remained in post until his retirement in 1914.

The Observatory on Western Terrace, Falmouth. RCPS Annual report 1885

The instruments from the Tower were reinstalled and others added in various locations in the new Observatory. A subterranean magnetic chamber in the main building held self recording magnetographs based on the Kew pattern and there was extra housing for magnetic readings in the grounds. In her book ‘Old Falmouth’, published in 1903, Susan Gay remarked on the magnetic chamber and the Observatory in general. ‘An hour at the Observatory quickly passes, as one becomes absorbed in viewing the ingenious sun-gauge, and the way the anemometer whirling in the breeze – records the force of the wind – with the various scientific processes, all self acting, which make the work of such an institution so accurate and useful.’

A Robinson Anemometer – Measuring Wind Speed and Direction.

The work of the Observatory continued with the support of the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society and the Royal Society until well into the next century but secure funding was a constant problem. There were technical advances which also put pressure on finance and there was also a move to a more centralised policy and control of information collection. In 1921 the Meteorological Council finally withdrew funding for the Falmouth station but the Observatory was a source of civic pride and the Town Council agreed to support the RCPS in continuing the work as a meteorological station. However, over the ensuing years the financial burden of maintenance and development increased whilst the efficacy of local stations decreased in relation to the more centralised national structure that developed after World War 2. The Observatory was closed in 1953 and the property was sold by the RCPS.

A Legacy

The Tower and the Observatory are still landmarks in the town but now both in private ownership and without their original purpose. Nevertheless they represent the importance of that purpose which had local, national and international impact. The interest, creativity and involvement of local meteorologists, both amateur and professional, was an important factor, not only improving safety at sea for maritime communities but also in developing the science and services of meteorology. Undoubtedly the meteorological work of the RCPS and the Falmouth Observatories as one of Society’s Annual Reports states ‘did much to encourage the science of meteorology’ and put Falmouth firmly on the meteorological map.

The Bartlett Blog

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. Watching Weather was written by Linda Batchelor.

The Bartlett Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.