The generous donation to the Museum of an extensive library of maritime books contained a special treasure which sheds a light on shipbuilding in the early 19th Century and the story of a local shipbuilding family.

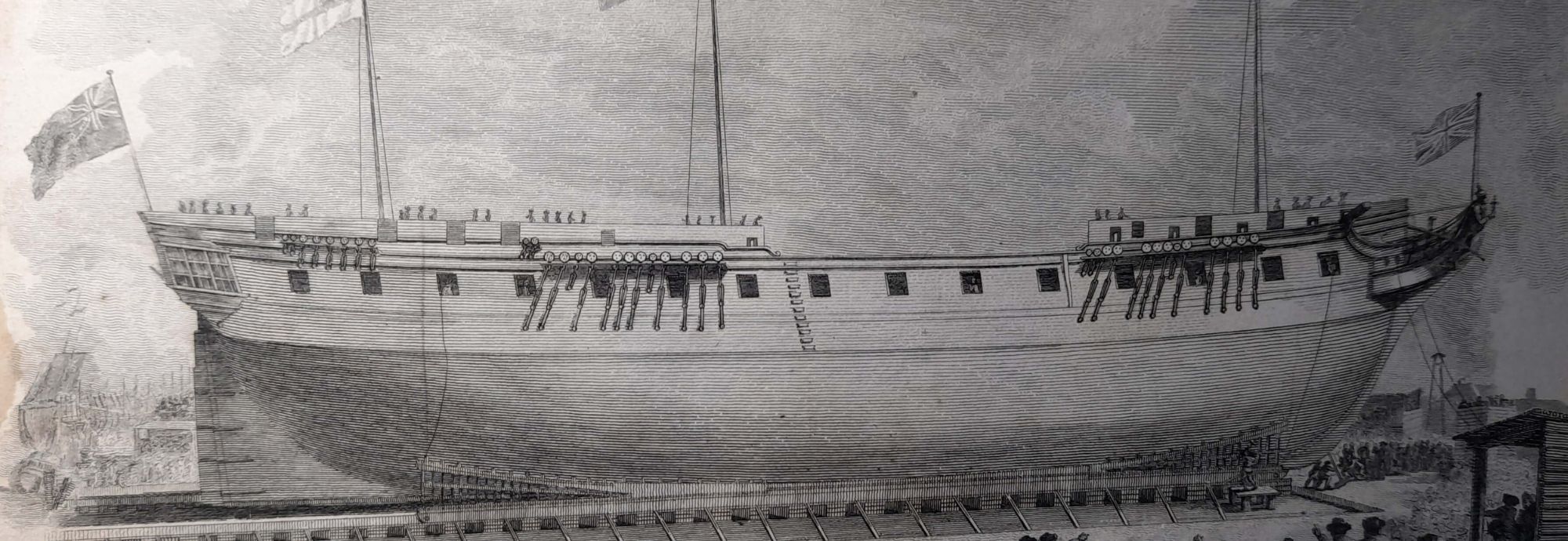

The leather-bound book is entitled The Shipwright’s Vade Mecum – a clear and familiar introduction to the principles and practice of Ship-building (and several more lines) was published in 1805. A Vade Mecum – literally ‘Go with me’ in Latin – is the equivalent of a ready-reckoner or essential handbook. This one is no exception. It attempts to describe in words everything one needs to know to build a ship as large as a 74-gun battleship, doing for ship-building what Mrs Beeton would do for household management in 1861.

The book opens with a lesson on the rules of arithmetic and geometry, before moving on to ship-building terms and principles.

The definition of ship-building terms is worthy of study. Who, in a pub quiz, could come up with a definition of a bumkin as a ‘projecting piece of oak or fir, on each bow of a ship, fayed down upon the false-rail, or upper rail of the head, with its heel cleated against the knight-head in large and the bow in small ships’, or knew that snying was a ‘term applied to planks when their edges round or curve upwards. The great sny occasioned in full bows or buttocks is only to be prevented by introducing steelers (see Steelers)’?

Some are clearer. Sliding keels are defined as being ‘an invention of the ingenious Captain Schank, of the Royal Navy, to prevent vessels from being driven to leeward by a side wind. They are composed of plank of various breadths, erected vertically, so as to slide through the keel.’ Surely, this is the first mention of a dagger- or centreboard.

The definition of yacht reflects the age and would be endorsed by any modern yachtsman: ‘A vessel of state or pleasure, usually employed to carry noble personages, and accordingly fitted with convenient apartments and suitable furniture.’

The book continues with instructions on how to design a ship, lay it out on the floor, and then provides practical directions for the actual building, starting, like Mrs Beeton with the basics ‘A slip being provided, the blocks are laid at the distance of about five feet asunder, to receive the keel, from which the structure is to be raised …’ At times the instructions read like those for modern knock-down furniture ‘Take piece A, while holding piece B in place, locate lug C in slot D …’

Frontispiece of the book: ‘Representation of a 40-gun Frigate, at the instant previous to her Launching’.

It ends with tables which set out all the principal dimensions and scantlings – ‘the dimensions given for the timbers, plank &c‘ – for ‘a 74 gun ship, a frigate of 36 guns, a merchant ship of 330 tons, a brig of 170 tons, and a sloop of sixty tons’ and for ‘long-boats, launches and a barge’. So, if you were planning to build a packet ship in the early 19th century, you had a full list of the wood you would need, and its dimensions, to assist you in estimating your shopping list.

There are no visual plans for any of the vessels. No doubt an experienced shipwright could work out the shape from these tables, knowing that the ‘station from the foremost perpendicular was 60ft 6in at station B’ and so on. Or perhaps they had read the earlier chapters.

The idea that years of ship-building knowledge could be captured in a single 343-page volume seems incredible to us today as we would expect that largescale plans, drawings, models and the like, would be used to build a frigate, not simply a set of tables in a book.

One wonders how many such vessels were built using this book: probably not many 74s or 36-gun frigates but the instructions for a 170-ton brig may have been useful for planning the building of a Packet ship. This is a real possibility for the book is inscribed Thomas Symons, 30th January 1818.

Born in in 1800, Thomas Symons came from a long line of shipbuilders and the book may have been a present on his eighteenth birthday. The Symons family had run the main boatyard in Flushing, Cornwall since at least 1760 and he was the fourth generation to be involved.

Originally known as Lobb’s Palace – Palace being a term for a pilchard cellar – and then called Little Falmouth, the business had done very well in the early years of the 19th Century, building large vessels for the Navy such as the Dispatch of 382 tons and the Avon of 391 tons. As many as six Packet ships are recorded as having been built here including the Marquess of Camden in 1827 and the tables in the book may well have been used for these.

Thomas would go on to take over the boatyard on the death of his father Richard in 1837.

1818 was a time of great change in the shipyard. The family had been given the right to build a dry dock, the Fal’s first, and this was to open in 1820. The dock eventually fell into disuse and was partially filled in in 1999.

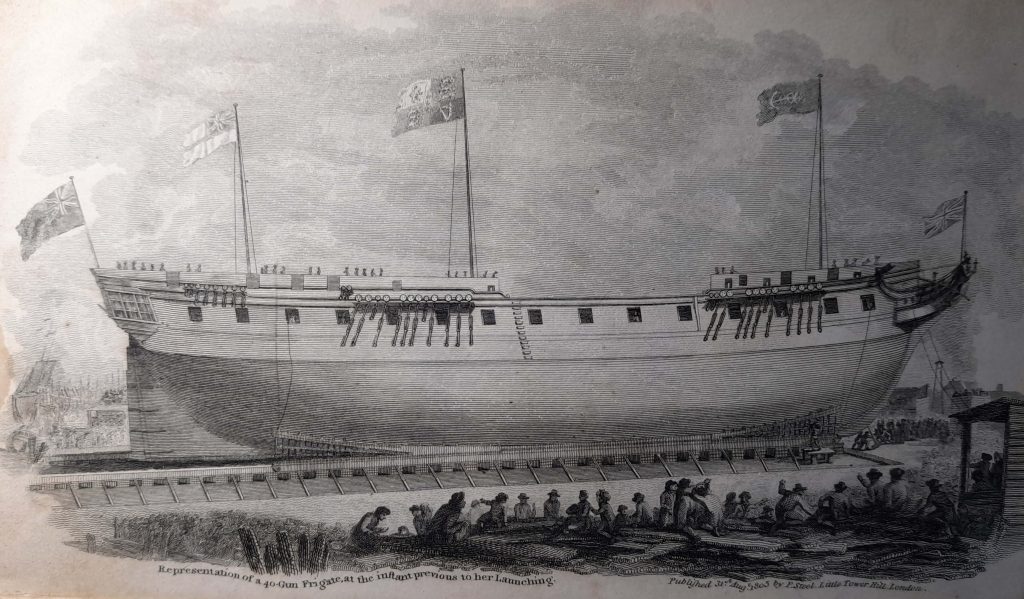

The best image we have of the shipyard at the time is in a picture from ca.1826 by the artist Thomas Daniell. This shows the sweep of the Penryn river, looking over Selly’s – or Sailor’s – creek. On the left is a fine row of buildings with a short pier. Two masts can be seen peeking over the hill.

The Penryn river – William Daniell ca. 1826.

Just off shore from the boatyard is a small gaff-rigged ketch which could be the earliest depiction of a Falmouth Quay Punt that we know of. The classic Quay Punt is not recorded for another 50 years and yet their design had clearly evolved from earlier craft on the Fal. This picture suggests that the basic sail shape was around much earlier.

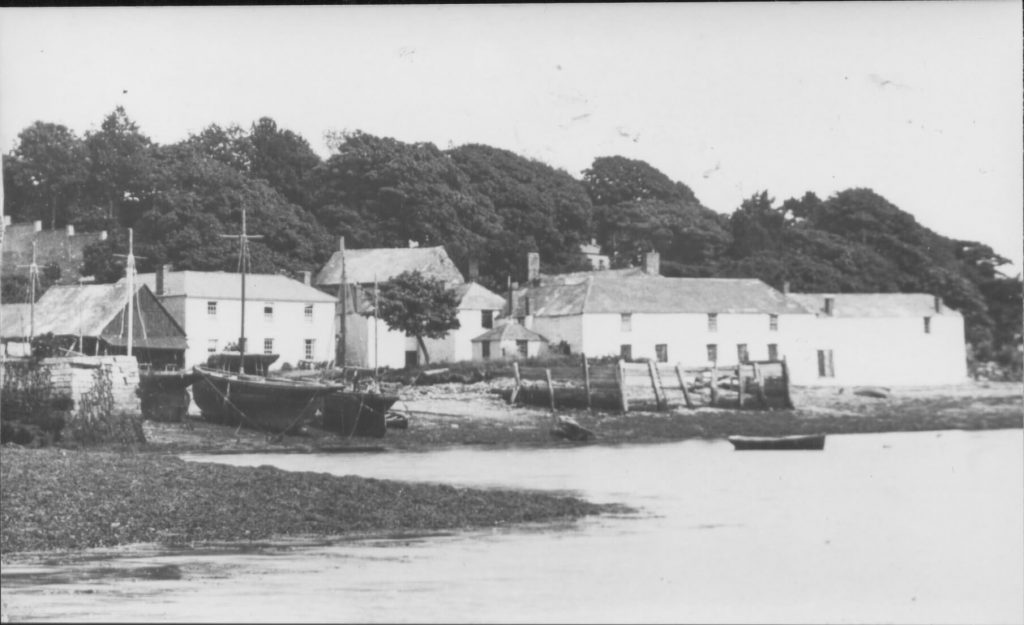

Daniell’s picture accords very closely with a photograph of the shipyard ca.1900. While the detail in the rest of Daniell’s picture is either fairly accurate or very vague, the buildings of Little Falmouth are depicted more precisely. One is left to wonder whether the Symons family therefore had a hand in the creation of the picture.

Little Falmouth ca.1900 (source: Bartlett Library).

Thomas ran the yard until his retirement in 1851 when Henry Trethowan took it on, ending a run of nearly 150 years of Symons control.

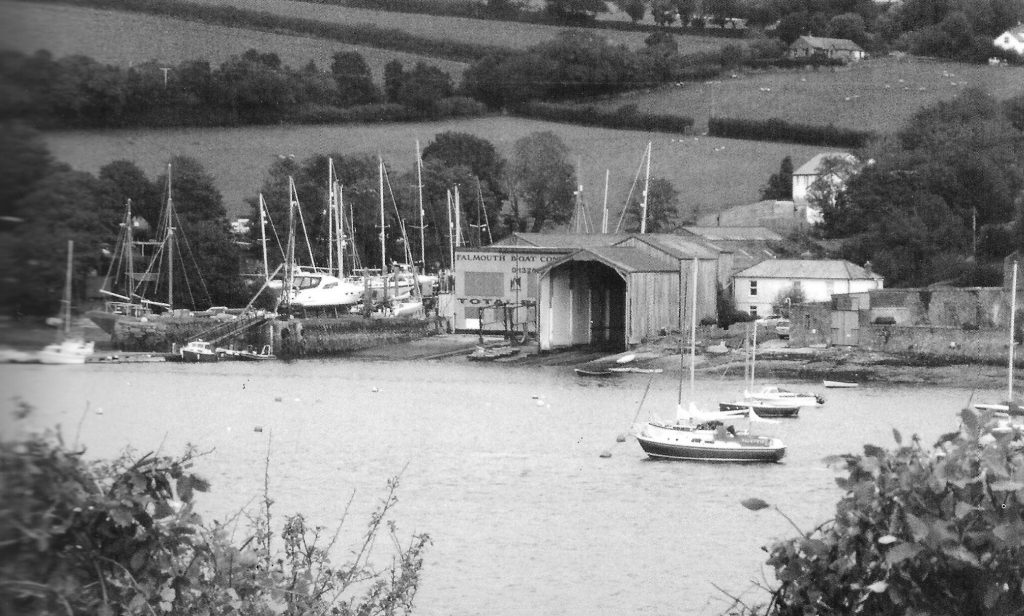

Henry Trethowan became bankrupt in 1876 when Little Falmouth was taken on by a Robert Lee who passed on the yard to Richard S Burt, famous for his Quay Punts and yachts, who moved from his shipyard on the Bar in Falmouth in 1928. It then had a succession of owners and is still active today as Falmouth Boat Construction.

Little Falmouth ca 1950 (source unknown).

Thomas died in 1860 and we know no more about the story of the book until it was gifted to the Museum in late 2023.

Amongst many pencil annotations and drawings in the book is a whimsical piece of doggerel:

High on the rock Pendennis stands

And with its thund’ring guns the port commands

While strong St Maudit answered it below

Where Falmouth strand the spacious harbour shows.

Note: St Maudit or Maudez is a historical name for St Mawes whose castle faces that of Pendennis.

The author would like to give due credit to Roger and Janis Winslade who kindly donated the book to the Bartlett Library; to the late David Wilson, former Volunteer in the Bartlett, for source material in his book Maritime History of Falmouth; and to the Volunteers in the Bartlett Maritime Research Centre.

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk