By Linda Batchelor

When Falmouth was chosen as the terminus of the international maritime mail routes in 1688, the Packet Service quickly became established in the town and the surrounding area. As the Service grew, so also did the need to accommodate the personnel involved.

This demand came not only from those in the associated trades and suppliers but from the crews and particularly from the Commanders. A number of the substantial houses occupied by the Commanders are still part of the housing stock in Falmouth, and some examples are considered in this blog.

Falmouth, established as a new town in 1661, with its deep estuary, good shelter and anchorage and located at the south-western approaches to the British mainland, became an important Packet station in 1688. The Post Office Packet Service became a dominant entity in the town until, after over 150 in service, the Falmouth Packet station finally closed in 1851.

The Post Office Packet Service was a branch of the Royal Mail, established to carry international mails and government dispatches, and sea links were an important part of the service. Packet ships were fast, lightly armed sailing vessels with regular sailings to and from Falmouth, initially serving Spain via Corunna and then Portugal via Lisbon. By 1705 there was also a regular service to the West Indies and the Americas.

HM Packet Sheldrake, Lieutenant Passingham Commander, entering Falmouth Harbour.

Nicolas Matthew Condy. NMM Greenwich.

The mails were packed in custom-made weighted leather portmanteaus designed to protect their contents and also to ensure that they could be easily jettisoned and sunk. In emergencies, such as attack, it was important that the confidential mails and dispatches should not fall into the wrong hands. The portmanteau was the last thing to be loaded at the start of a Packet voyage and the last to be landed at the end. In peacetime, the mails were stowed in a compartment on the orlop under the cabin, but in wartime the mail was kept on deck

Until 1823, when it taken over by the Admiralty, the Packet Service was a civilian service under the control and management of the Post Office. During that time the Post Office used sailing vessels hired directly or through their commanders, many of whom owned or had shares in the vessels. Commanders held a Post Office commission and appointed their own crews who were exempt from impressment. At its height, the service employed over 1,200 seamen.

Commanders and their crews not only faced the usual dangers and privations of life at sea, such as shipwreck, disease and death, but they were often open to attack from enemy ships, privateers, and sometimes pirates. As the European powers battled for supremacy at sea, and during times of warfare, the Packet ships sailing on the routes to the Mediterranean, North and South America, and the Caribbean with confidential mail and dispatches, valuable cargo and a compliment of passengers, were under constant threat.

The Packet Memorial on the Moor at Falmouth, ‘Erected to the Memory of the Gallant Officers and Men of HM Post Office Packet Service Sailing from Falmouth 1688 – 1852.’

Packet Commanders were prominent members of the community with considerable social standing around Falmouth. They had a high profile in the town and, although there was no official Packet Service uniform, they assumed dress very similar to Royal Navy officers. To distinguish them, the Admiralty instructed the Post Master General in 1787 that button holes on their uniforms should ‘be embroidered in silver instead of gold and the Buttons of white metal instead of being gilt’.

The pay for Commanders was modest, but many accumulated wealth, particularly the senior Commanders on the Lisbon run. Some Commanders were packet owners or shareholders and had interests outside the Packet Service. All could make profits from the carriage of freight and passengers and especially from the shipment of bullion. As Tony Pawlyn, an expert on the Packet Service, has said of bullion shipment, ‘Just taking a look at the houses built by the Packet ship captains in Falmouth gives you some idea of just how lucrative it was.’

The houses of Falmouth Commanders, sometimes owned or more often leased, reflected their social standing, and many of those houses are still in existence today. Initially, Flushing, the village across the water from Falmouth, was popular as residences for Commanders but as the town grew, the Green Bank area and other parts of the town also proved to be attractive.

Flushing was already recognised as a seaport before Falmouth received its Royal Charter in 1661. The Trefusis family who owned the land used Dutch engineers to build docks and quays on the waterfront, which may have been the origin of the name of the village. The hamlet quickly became a place for loading and unloading vessels using the Fal estuary and, with the Packet Service established at Falmouth Samuel Trefusis (1676-1724), developed the village to victual and support the Service and to provide storage facilities.

Samuel Trefusis also provided a range of housing for Commanders, officers and crews and for many years Flushing with its facilities, the ship building and repair yards, became a favoured place for many captains and officials to live. A number of substantial houses built on St Peter’s Hill (originally known as New Road) with a view over the Packet moorings in Falmouth were occupied by a various Commanders during the late 18th century.

St Peter’s Hill, Flushing showing No 5 home of Edward Pellew and No.4 (far right) home of William Kempthorne.

As time progressed, Falmouth grew and prospered. The town became a fashionable place to live and the stock of substantial housing grew, particularly in the area around Green Bank with its terraces overlooking the water and the packet moorings. The Bassets of Tehidy had extensive mining and business interests and they owned land throughout Cornwall. In the early 1800s, the Basset estate released land in Falmouth and built a number of elegant houses on Dunstanville Terrace.

Dunstanville Terrace, built in Falmouth to house Packet Captains and merchants.

The terrace overlooking the stretch of water known as the ‘Kings Road’, where packet ships were moored, was named for Francis Basset who became Baron de Dunstanville in 1796. Houses here and the surrounding terraces soon attracted the Commanders and officers of the Packet Service. However this was sometimes a mixed blessing as these houses often suffered from equipment being stored around the property and from the heavy traffic of crews coming and going which often raised concerns from the owners agents.

Many of these houses still exist in Falmouth, Flushing and the surrounding areas and their stories provide interest into the personalities and the infrastructure created by the Packet Service. Here are a few examples of such houses and some of their occupants. Not only do they provide an insight into how many Packet Commanders lived during the 18th and 19th centuries but they also provide history, relevance, elegance and continuity in the housing stock of the modern town.

Kempthorne House, 4 St Peter’s Hill, Flushing

The house was built around 1770 and was one of the substantial houses in what was originally known as the New Road, later St Peter’s Road. The houses were near the ship building and repair yards of Little Falmouth and had views over the Packet moorings in the Fal.

This was the home of William Kempthorne, a well-known and highly respected Commander of Packet ships such as Grenville and Antelope. William came from a West Country family with strong naval connections, and his wife Elizabeth was the daughter of a Commander in the Packet Service.

It was from this house that from the 1770s to the 1790s William departed as a Commander of Packet ships on the routes to North and South America and the Caribbean, and it was here William and Elizabeth raised their six children. In 1783, the house next door to the Kempthornes, Number 5, was leased to the newly married Edward and Susan Pellew.

Edward Pellew had close connections with Flushing as his Grandfather Humphrey Pellew, a merchant and ship owner, had been closely associated with Samuel Trefusis in the development of the area. Edward served with distinction as an officer in the Royal Navy throughout the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary War, and the Napoleonic War. He was honoured with a knighthood and created a baron for his exploits against the French as Commander of HMS Nympe and HMS Indefatiable whilst his home was in Flushing.

A considerable friendship developed between the two growing families and especially between William and Elizabeth and Edward and Susan, doubtless enhanced by their seafaring connections. It is said that an internal door was cut between their houses to facilitate the frequent comings and goings of the families.

In 1793, William prevented a riot by three hundred miners in Flushing. At the time, the price of corn was high, there was resentment and distress in some communities, and groups of rioters formed to try to force the price down. This was particularly true amongst the mining community and angry miners descended on Flushing where grain was being unloaded. According to contemporary accounts, Captain Kempthorne quelled the anger by speaking to the men and leading them in hymn singing so that they dispersed peaceably.

From the late-1770s William Kempthorne was the Commander of HMP Grenville, the second packet ship of that name. Built in Spain in 1768, the ship had been taken as a prize from the Spanish and repurposed and renamed as a packet on the Atlantic routes. Grenville and Captain Kempthorne were frequently involved in incidents at sea.

In March 1778, for example, during the American War of Independence, Grenville, under Kempthorne’s command, was attacked when approaching Barbados by the Continental Navy sloop Resistance. In the ‘smart engagement’ which followed, the mails which had been hung over the ship’s side to avoid capture were shot away by a stray shot and sank. The American ship was beaten off and headed for Martinique with the Captain and three others killed, and at least twelve of the crew wounded. On Grenville, William had the roof of his mouth shot away and the sailing master and seven others were wounded. The Packet arrived in Barbados ‘in a shattered condition’, and when it sailed for the to return to Falmouth, William was left in the West Indies to recover from his injuries. Despite the fact that the mails had been lost, the Captain and the crew were rewarded by the Post Office and William received £100 as his share.

A new Packet ship, HMP Antelope, was built for the Atlantic routes and launched in 1780, and once again this ship was commanded by Captain Kempthorne. Over the next decade with wars still raging, the Packets were open to frequent attacks. Antelope was captured by the French first in 1781 and then again in 1782 when she was and taken to Nantes, ‘and is since purchased by Capt. Kempthorne who is now gone to bring her home’ (Falmouth Packet Archives).

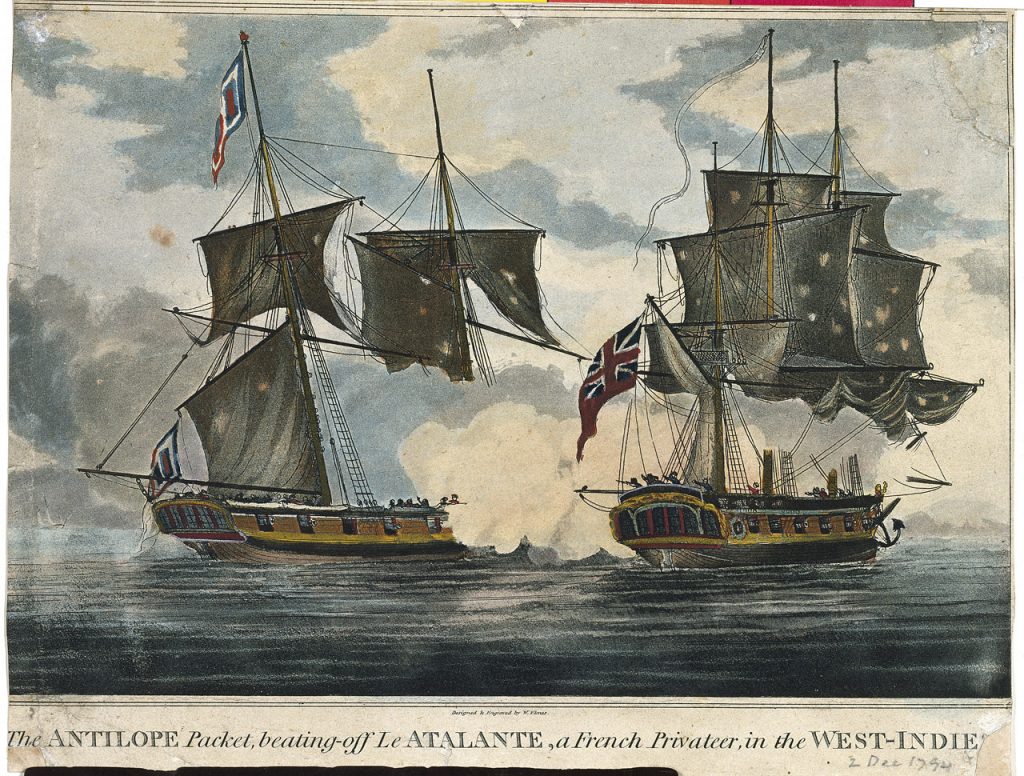

The Engagement of HMP Antelope and the French Privateer Atalante off Jamaica

William Elmes. NMM Greenwich.

In 1793, Antelope was sailing for Jamaica under her Sailing Master, Edward Curtis, as her Commander was sick at home. The packet was engaged by the French privateer Atalante more heavily armed with a crew of twice the size and a fearsome reputation. Despite the odds, the packet fought off the attack. Edward Curtis and his steward were killed, but command was taken by the boatswain, John Pascoe, and the privateer was taken as a prize to Jamaica. The crew were officially rewarded both in Jamaica and England.

The following year, William was once again in command and sailed from Falmouth for Halifax with a crew of thirty on 19th August. On 19th September, in a dense fog, they met and were surrounded by a squadron of French frigates. The crew sank the mails, surrendered to the French ship Surveillante, and were taken prisoner. Commander William Kempthorne died of yellow fever whilst in captivity. He left behind his widow Elizabeth and six children to be supported by a small pension from the Post Office. His friend Edward Pellew took William’s son, also William, to sea as a Midshipman in the Royal Navy where his naval career subsequently flourished.

William Kempthorne had been a popular man as a Packet Commander and a member of the community in Flushing and Falmouth, and he was widely mourned in the Packet Service and the neighbourhood.

Penmere House, built by Packet Commander John Bullock, now the Penmere Manor Hotel.

Penmere House was described in an advert for a lease in the Royal Cornwall Gazette of 1829 as, ‘most delightfully situated and within ten minutes walk of the town of Falmouth’. The house was built in 1825 by Captain John Bullock of Falmouth, a successful owner and Commander of Packet ships, with a considerable social standing in the town.

Although not looking out over the harbour, the central axis of the house is designed to lead the eye towards the sea at Swanpool. As well as the main dwelling house, there was also a coach house, stabling, a walled garden, lawns, and about 18 acres of rich fertile land. The house illustrates the wealth of some Packet Commanders in Falmouth and the substantial nature of their residences.

John Bullock was born in Falmouth in 1778, the son of Peter and Eleonor Bullock of Falmouth where he grew up. He was married three times. First to Sophia Wolfe, daughter of Captain Wolfe, in 1797, and had a son John James Adolphus Bullock in 1799 who became a surgeon. After her death he married again in 1813 to Patty Bawden, and a second son, Edward Bawden Bullock, was born in 1814 who became a clergyman. By 1815 he was a widower once more and he married Elizabeth (Betsey) Lovell for whom he built Penmere House and laid out the grounds and who outlived him. By the time of his death he was a wealthy man owning not only Penmere but other properties including two in Penzance and the Navy Tavern in Falmouth.

As a young man John Bullock joined the Packet Service serving in both the civilian service and under Admiralty control from 1823 as Lieutenant Bullock R.N. From 1808 until 1812 he was in command of the temporary Packet Express which had been captured as a prize from the French, and after re-fitting was sailing as a Packet from 1809. He was wounded on board whilst resisting enemy action.

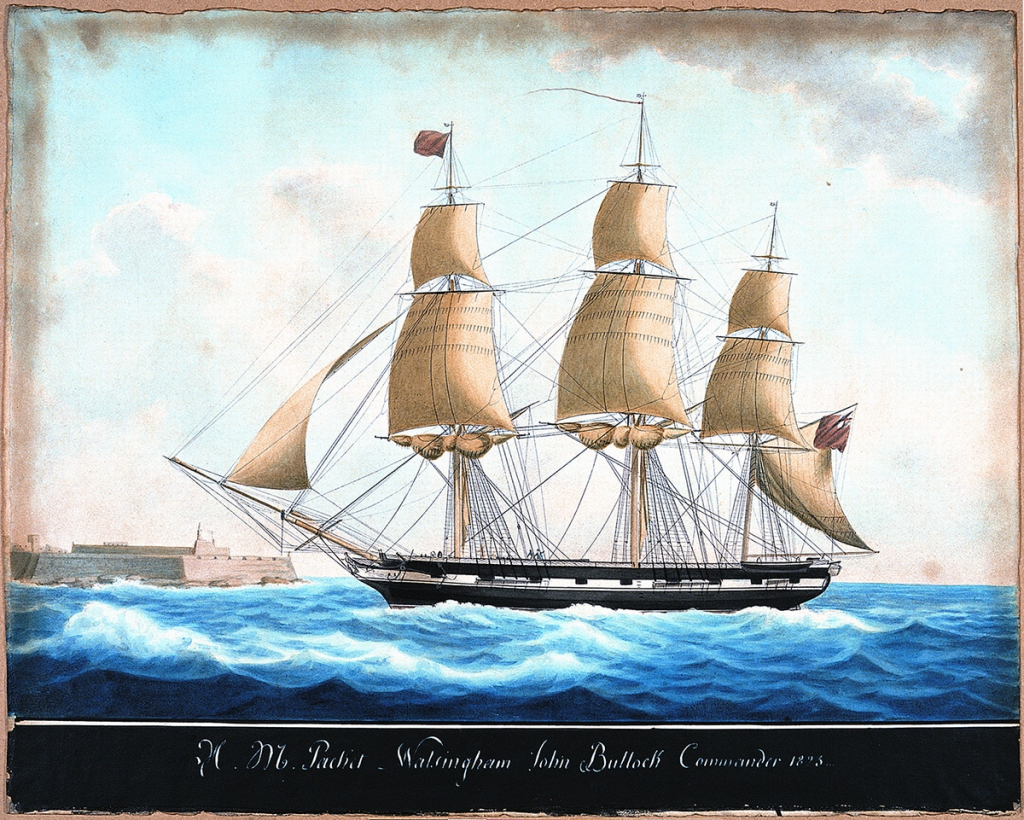

HMP Walsingham had a notable career as a Packet ship from 1794 to 1825. The ship was one of the new ‘standard’ packets introduced by the Post Office in 1790. Originally built for Captain Couse, the ship was commanded over that time by a number of Packet captains. John Bullock received his commission as Commander in 1812, and from 1813 was listed in Lloyd’s Register as owner and Commander until the ship was sold out of the Service in 1826.

Until 1808, she served the Lisbon and Mediterranean routes, but in 1809 she carried the first mail from Falmouth to Rio de Janeiro and thereafter was mainly sailed to the Brazils and North America. In 1817, Walsingham, under the command of John Bullock, set the fastest time of 82 days for a sailing Packet for the round trip to Rio de Janeiro.

HM Packet Walsingham, Commander John Bullock, entering harbour in Malta in 1823.

Nicholas Cammillieri. NMMCornwall.

When the Packet Service came under Admiralty control in 1823, John Bullock was transferred as Commander to HMP Redpole, a 10-gun brig. The vessel, a Cherokee class brig, had been launched in 1808 and, as part of the Royal Navy, saw service throughout the Napoleonic wars. At the end of the wars in 1824 and 1825, Redpole was converted at Plymouth to serve as a Falmouth Packet on the Atlantic routes.

Despite the end of hostilities, packet voyages still held dangers, and in 1828 this proved to be the case for Redpole on a voyage to Rio de Janeiro. Redpole left Rio for the return voyage to Falmouth on 10 August 1828 under the command of Captain Bullock, due at the end of September. She never arrived. On 29th September, the Royal Cornwall Gazette reported, ‘We are sorry to observe that another week has elapsed without any tidings of the Redpole packet, for the safety of which very slender hopes can now be entertained.’

It was later reported that the vessel had been attacked off Cape Frio by Congress, an 18-gun privateer from Buenos Aires. No more was heard of the packet, her Commander and his crew, and eventually they and the vessel were presumed lost.

John Bullock left behind a widow and two sons and his recently built home of Penmere House. After Commander Bullock’s presumed death in 1829, the house was leased to Augustus Passingham, another Packet Service Captain. Subsequent residents came from the mining and mercantile community and, after a number of other uses, the house became the present Penmere Manor Hotel.

Windsor House and Montague House are two of the more imposing houses built at the western end of Dunstanville Terrace in Falmouth. The house is one of two built at the same time and both named after packet ships. Windsor House was named after the Windsor Castle Packet and was probably originally occupied by Commander William Rogers. It was his exploits as temporary Captain of the packet that earned him promotion to Commander and standing in society.

William was born in 1778 and, after joining the Packet Service, rose through the ranks until he became the Sailing Master of the new packet Windsor Castle in 1804. Sailing masters undertook the navigation of the packets and advised on ship handling. They took command of a vessel if the Commander was unable to do so and often undertook voyages as temporary captains. Windsor Castle was owned and commanded by Captain Sutton and spent 11 years serving as a Falmouth Packet, mainly on the routes to North America and the Leeward Islands.

William had a career full of incident throughout the turbulent period in which he served. In 1795, at 17 he joined the Countess of Leicester Packet, which two years later was captured, her crew imprisoned and then exchanged. On his return to Falmouth in 1798, William joined the Carteret to be captured and exchanged in 1800, and in the following year he was captured whilst serving on the Duke of Clarence, but this time he escaped and returned home aboard an American ship. He served briefly on the temporary packet Penelope before transferring to the Duke of Kent only to be captured again in 1804 before release after four months. It was then that he joined the Windsor Castle as Sailing Master, and it was in 1807 when he was given temporary command when the regular commander was on leave that he and his crew distinguished themselves in resisting an attack by a privateer.

As the packet on a Leeward Island voyage approached Barbados, Rogers and his crew were chased by the French privateer Le Jeune Richard. The privateer was heavily armed with a crew of 96 against the lightly armed packet with its limited fire power and a crew of only 28. In the account by a passenger written on return to Falmouth, ‘all hopes of escape by swiftness was in vain’. The crew of Windsor Castle prepared themselves to resist and, ‘the Captain all the while giving his orders with admirable coolness and encouraging his men by his speeches and example, in such a way, as there was no thought of yielding.’

After the privateer closed in and grappled with the packet, Captain Rogers and his crew fought hard and bravely to repel the attack and, during several hours of bloody fighting, three men were killed and only 16 of the crew remained uninjured. Finally, the Captain and five or six of his men boarded the enemy ship, tore down her colours, drove the remaining crew below decks forcing their surrender, and took Le Jeune Richard as a prize.

Captain Rogers and his crew returned home as heroes. Rogers received a large financial reward and the crew were all rewarded with sums of money proportionately and according to rank. Rogers was awarded several swords of honour, promoted to Commander and given command of a new packet, Countess of Chichester. The action was commemorated in a painting by the contemporary artist Samuel Drummond exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1808. Drummond also painted a bust-length portrait of William.

William Rogers Master of HMP Windsor Castle.

Samuel Drummond (1765-1844) NMM Greenwich.

Commander Rogers remained in command of the Countess of Chichester for many years. During that time he lived in Falmouth and some of that time in the house named for his 1807 exploit on Dunstanville Terrace. From here he would have been able to see his ship lying at anchor in the King’s Reach. He later left Falmouth and transferred to the Holyhead Packet Station in Anglesey, North Wales. His working life was dedicated to the Packet Service. It was doubtless a rewarding and at times exciting life, but also a rigorous one, and William died aged only 47 in 1825.

Marlborough House, Falmouth.

Marlborough House was built around 1810 as the home of the celebrated Packet Commander John Bull. The house, originally called Marlborough Cottage, is of significant importance in Falmouth and is Grade II listed. Named after Commander Bull’s packet the Duke of Marlborough, a relief of a ship is featured on the front of the building. The house reflects the wealth and social standing of its original owner.

The Ship Relief on Marlborough House. Photo by Lynne Vosper.

John Bull was born in Falmouth in 1772 to a family employed in the Packet Service over three generations, and his father James had been a Packet Captain. John became one of the best known of the Commanders, ‘whose name is truly characteristic of his spirit’, and had a reputation as a bluff, plain speaking and larger than life character.

He spent 45 years in the Packet Service and became one of the senior Commanders of the service on the lucrative routes to the Lisbon station. During his service he commanded three packet vessels, the Grantham (1798 – 1800), the Duke of Marlborough (1802-1804) and a second Duke of Marlborough (2) (1806- 1832).

He was involved in numerous skirmishes. One occurred close to home in 1810 in Falmouth Bay as the packet was approaching home. They encountered a mysterious vessel in a fog which when challenged refused to show their colours. It was an enemy ship from the French fleet and the two vessels engaged with an exchange of fire, and the French attempted to board the packet. Commander Bull urged his crew to resist in the strongest of terms and the enemy vessel was beaten off. Another incident was one of friendly fire in 1814 with HM Brig Primrose. The naval Commander assumed that the packet was an enemy vessel even though Commander Bull made the appropriate identification signals. This led to a running fight of two and a half hours with casualties on both ships before the naval commander realised the mistake. John Bull had many such incidents throughout his career and was wounded several times in the course of his service.

Marlborough Cottage had an estate of 30 acres which looked over Falmouth Bay and Swanpool, and it was proof of the prosperity he acquired as an owner and Commander in the Packet Service. In 1799 he had married Phillipa Powel, and they had lived in Number 7 St Peter’s Road in Flushing until her death in 1807. He moved back to Falmouth and married for a second time to Phoebe Marshall in Lisbon, returning to the newly built Marlborough Cottage.

Unlike the other three Commanders, John Bull survived an incident-packed career and lived to enjoy a wealthy retirement of nearly 20 years.

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk