Linda Batchelor

In 1746, William Cookworthy, a Quaker apothecary and chemist from Plymouth, was visiting a fellow Quaker Richard Hingston, a surgeon in Penryn, Cornwall. It was during the visit at the Great Work Mine at Tregonning Hill, near Helston, that William discovered a source of clay which was to lead to developments in English porcelain and the birth of the China clay industry in Cornwall.

As demand grew from the centres of porcelain manufacture for the raw material, which became known as white gold, so too did the means of transporting the China clay which in turn led to the construction of harbours such as Charlestown, near St Austell, for its export.

The Clay Pit c 1925 Harold Harvey (1874 -1941)

Image Credit Royal Institution of Cornwall

China clay is the common name for kaolin, which is a hydrated aluminium silicate crystalline mineral. The fine mineral deposit is the result of hydrothermal decomposition of granite rocks and the deposits around St Austell in Cornwall were once the largest in the world. The area became the centre of China clay mining, extraction, and export. By the mid-19th century, 65,000 tonnes were mined every year and Cornwall monopolised the world supply.

China clay in crushed form

Photo Credit: Imerys

Kaolin was used over centuries in China and the far east to produce porcelain, and during the late seventeen century traders began bringing porcelain to Europe. This ‘china’ was desirable and the interest in finding a source of suitable clay for western manufacture began. It was this interest that led William Cookworthy and his associates to his discovery in Cornwall.

The China clay industry grew rapidly around St Austell, dominating the landscape and employing large numbers of the population either directly in the mining operations, the processing of the material, or the transportation of the product or indirectly in the many related businesses. In 1919 the three main producers were formed into English China Clays which dominated the market until bought by Imerys, a French company, in 1999. Although considerably diminished as most of the production has moved elsewhere in the world, the industry in Cornwall continues to supply the market and the product is still shipped all over the world.

The clay is mined in open cast pits using high pressure water and the resulting slurry is dried and processed into the material used not only in porcelain manufacture and ceramics but in a myriad of manufacturing processes such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, paint, and many others.

China Clay Workings in St Austell, Cornwall 1974

Historic England Educational Image

William was born in 1705 in Kingsbridge, Devon, to a Quaker family where his father was a weaver. William’s father died in 1718 and at the age of 15 he was apprenticed to two Quaker brothers, Timothy and Sylvanus Bevan, who were London apothecaries. The Cookworthy family had been left in difficult financial circumstances and, unable to afford the coach fare, William walked to London to take up his apprenticeship.

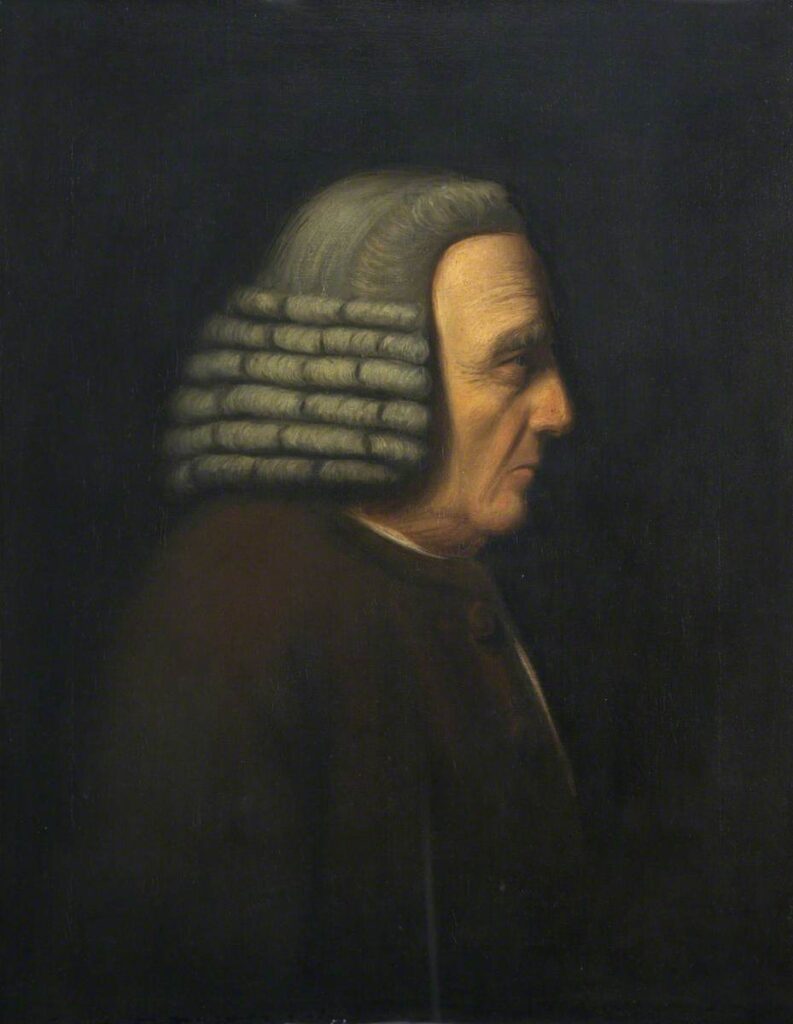

William Cookworthy (1705 – 1780) Portrait by John Opie (1761 – 1807)

The Box, Plymouth

He flourished during the following years studying drug dispensing and chemistry and learning Latin, Greek, and French. When he had finished his apprenticeship he was taken into partnership by the Bevans and moved to Plymouth to set up Bevan and Cookworthy, wholesale chemists and druggists in Nore Street.

He built up a wide range of connections particularly in Devon and Cornwall through the pharmacy business but also through his prominence in Devon and the South West of England as an active Quaker and through his scientific interests. The engineer John Smeaton lodged in William’s house from 1756 to 1759 whilst building the Eddystone Lighthouse, and William advised him on the use of hydraulic lime in the construction. He received visits from explorers and scientists such as Captain James Cook and Sir Joseph Banks and he was consulted by the Navy on the use of fresh fruit and vegetables for the prevention of scurvy.

It was also through his connections that William was visiting Richard Hingston, a Quaker surgeon in Penryn and a relative of the Fox family of Falmouth, when he was invited to the Great Works Mine in search of kaolin deposits. William’s interest had been triggered in finding a source of the material in England in 1740 when reading a Jesuit missionary’s description of the manufacture of Chinese porcelain.

After the death of his wife, mother of his five daughters, in 1745, William bought out the Bevans from the Plymouth pharmacy. He took his brothers Philip and Benjamin into partnership to run the business and he began to concentrate on his religious and scientific interests. He became more involved as a Quaker minister and as a religious thinker and translator. He also began travelling over Devon and Cornwall searching for minerals.

On his visit to the Great Works Mine, William noted the fine clay known locally as moorstone that the miners were using to repair the furnaces. He leased some of the clay pits at Tregonning Hill, near Helston, and shipped the clay from Porthleven to Plymouth. He began experimenting with the clay using water to separate the material from impurities. This first find had a considerable amount of impurities in the clay which were difficult to separate and left black specks of mica after the clay was fired. With more searching better, purer and larger deposits were found at St Stephen in Brannel, near St Austell, on land owned by Thomas Pitt, later Lord Camelford, who helped financially when William took out a patent for the manufacture of porcelain.

After further considerable experimentation in 1768 William opened a small porcelain factory at Coxside, Sutton Pool in Plymouth, using clay from the St Austell deposits. The manufactory was financed by William, other local businessmen, and a group of Quakers from Bristol. The works ran for two years in Plymouth before being transferred to Bristol and was overseen by William until 1773 when he decided to sell the factory. He sold that and his patent rights to his business partner and cousin Richard Champion but retained and received royalties on every item sold.

William continued to pursue his other interests such as his ministry and scientific interests including an essay contribution to William Pryce’s Mineralogia Conubiensis in 1778. He died in 1780 and was buried in Plymouth in the Quaker Burial Ground.

As a result of his discovery, the English porcelain industry grew and flourished, and for the ensuing centuries the China clay industry became dominant in the area around St Austell and a major part of the Cornish economy.

Charlestown is a village and port on St Austell Bay on the South Cornish coast, approximately two miles southeast of St Austell town centre. The harbour is the last open 18th century Georgian harbour in the UK and is Grade 2 listed. It is also part of the listing of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Cornwall and Devon Mining Landscape. It was built in the late 1700s by the land owner Charles Rashleigh as a port, initially to export copper from the surrounding mines but as the China clay industry grew around St Austell it prospered from the export of the ‘White Gold’ as the clay was known.

Charlestown Harbour as it is today.

Charles Rashleigh, after whom the harbour is named, was a wealthy lawyer, estate manager and landowner. He was a successful entrepreneur with commercial interests in property, land development and the burgeoning mining industry around St Austell.

He was born in 1747 at Menabilly, near Fowey, the tenth child and seventh son of Jonathan and Mary Rashleigh. The Rashleighs were a family of powerful merchants and landowners in the area since Tudor times and Jonathan was the Member of Parliament for Fowey with considerable property ownership in Cornwall.

Charles became a lawyer but on the death of his father when his elder brother inherited, he began managing the estate and developing his wider commercial interests. He purchased a large town house in St Austell, now the White Hart Hotel, and in 1775 he began building Duporth Manor outside St Austell probably in anticipation of his marriage in 1776 to Grace Tremayne of Heligan. In 1783 he became the principal partner in Polgooth Mine and over time invested in other local mining ventures which led him to develop a harbour on his land to export the copper from his mining interests and to bring in coal from South Wales.

The site of the new harbour was a mile away from Duporth Manor and was a small fishing hamlet known as West Porthmeur, or Polmear. Rashleigh employed the civil engineer James Smeaton to advise him and design the new harbour and construction on the inner harbour began in 1790. As well as the harbour, houses and workshops were built, and a working village grew up to service the harbour. A gun battery was built to protect the village, dock gates were installed in 1799 and the new port was named Charlestown. The initial construction was completed in 1804 although Smeaton did not live to see it. In 1790 there were just nine fishermen and their families living in the hamlet but by 1810 the population had risen to approximately three hundred and to three thousand by 1860.

By the time the harbour was first completed, Charles Rashleigh was already beginning to suffer financial difficulties. He was defrauded of much of his wealth by one of his servants and in 1807 his copper mine closed. By the time of his death in 1823, having been defrauded a second time Charles was bankrupt and the harbour was purchased by Messrs Crowder and Sartoris and set up as the Charlestown Estate.

The export of copper began to decline but as the China clay industry grew so too did the need to ship the product from Cornwall to the manufactories elsewhere in Britain and abroad. Charlestown was well placed to do so, and the port thrived with the constant business of transporting the clay from the mines to the ships. This continued until the outbreak of the Great War when there was a reduction in manufacturing and export. As steam replaced sail the harbour was unsuitable for the larger vessels and the nearby port of Par took precedence in the trade. Charlestown continued to function as a clay port, but it gradually declined over the years until the last commercial shipment of clay left in 2000.

China clay is transported, after processing, as a powder. In the 18th Century, transporting goods was largely by road using wagons and packhorses but from a coastal county such as Cornwall passage by sea was often a better and quicker option. Charlestown was the first port to serve the mines of the St Austell area and was initially built to export copper ore by sea to the Humber and bring coal in return. As the copper boom in the area began to diminish and China clay mining grew Charlestown became important and the clay was brought to the port in horse drawn wagons from the quarries and processing sites for shipping. The ‘White Gold’ left a visible presence along these routes and in the port where it was loaded down wooden chutes into the ships.

The schooner Fortuna in Charlestown Harbour loading clay from dockside chutes in 1934

David Weller Collection National Maritime Museum Cornwall

After 1859, the coming of the Cornwall Railway and the subsequent development of the rail network provided another means of transport for the clay. Ships and Charlestown continued to play a major part in its transportation during the boom years of the industry when it provided 50% of the world trade in China clay.

The Mary Miller, a three masted topsail schooner of 99 tons, was one of the last engineless sailing ships to be used in the clay trade. The vessel was the second of six built for James Fisher & Son of Barrow by the Paul Rodgers Shipyard in Carrickfergus, Ireland and was launched in April 1881.

Originally the Mary Miller was used in the deep-water trade but after a short spell spent most of her working life in the coastal trade around Britain. This trade often involved carrying China clay from Charlestown to the Humber from where it was transported to the centres of ceramic manufacture and returning with coal to various Cornish ports. After changing ownership a number of times, she was sold in 1938 to Charles Couch of Fowey and continued in the clay trade. At the start of the Second world War the vessel was fitted with an auxiliary motor and served as a balloon anchorage at Greenock and afterwards became a houseboat on the River Mersey, surviving until 1960.

The three masted topsail schooner Mary Miller off Falmouth in 1938

David Weller Collection National Maritime Museum Cornwall

The importance of Charlestown declined with changes in the 20th century and when the last shipment of clay left in 2000 it marked the end of the long working relationship between Charlestown and China clay.

The harbour has since been purchased by private enterprise and still functions as a working port with classic sailing vessels. The port has been preserved and still provides the historic link to the role it played in the China clay industry It has also become a tourist destination giving an insight into its history, a venue for sailing and other events and the location for many film and television productions.

Charlestown Harbour with a historic ship moored at the quay

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk