In the summer of 1940, as Nazi forces swept across Europe, one family’s dramatic escape from France would alter the course of history. While General Charles de Gaulle made a flight to London to continue the fight against German occupation, his wife Yvonne and their children were embarking on their own perilous journey. This blog post explores the story of the de Gaulle’s escape, finding refuge across the Channel.

By Linda Batchelor

Bordeaux Refugees at Falmouth (Art.IWM ART LD 747) Copyright: © IWM. Original Source.

After a period of unrest and political uncertainty in Europe in the late 1930s, Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. Two days later, 3 September, Britain and France declared they were at war with Germany and the World was plunged into the beginnings of a Second World War. Later in May and June 1940 the fortunes of war turned against the Allies leading to large scale evacuations from France. Amongst those who escaped to fight on were General de Gaulle on a British aircraft from Bordeaux to London and his wife Yvonne and their immediate family who escaped on a British ship Brest to Falmouth in June 1940.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commanded by Lord Gort moved to France on 3 September. From the outset in 1939 the majority of troops, BEF, Belgian and French, were maintaining defensive positions along the Belgian and French border. This period known as the phoney war lasted until May 1940 when the German Army advanced into France forcing the Allied troops back to the coast and the need for rescue.

The evacuation from Dunkirk (Operation Dynamo) was described by Churchill as a ‘miracle of deliverance’ and rescued more than 330,000 Allied personnel, mainly troops, from the beaches. The evacuations from the western ports of France (Operations Cycle and Aerial) were as large in scale involving a mix of troops, evacuees and refugees.

Operation Ariel Map

The German invasion of Poland on 1 September was the beginning of the war in Europe and the deployment of the BEF to France. Initially the purpose was defensive but during that time the German Army was advancing on other European countries. Denmark and Norway were attacked on 9 April 1940 with Denmark surrendering and occupied immediately. Norway resisted for two months until 9 June. By that time the Battle of France had begun on 10 May with two German armies moving eastwards invading and occupying Luxembourg within one day, the Netherlands surrendering and occupied on 15 May and Belgium on 28 May.

The major attack on France and the BEF came as Belgian resistance collapsed with the German army encircling the French and British troops and forcing them towards the Channel coast of France at Dunkirk. It was here that Operation Dynamo carried out by over nine hundred ships of the Royal Navy, merchant vessels and a flotilla of ‘little ships’, rescued Allied personnel from the beaches. The Admiralty signalled completion of this evacuation on 4 June 1940.

However, many British and Allied troops, including Polish, Czech and Belgian, were left in Western France. Some were combat units such as the British Highland Division, others were support and line of communication staff, RAF ground staff, medical and embassy and consular staff. There were also considerable numbers of civilian evacuees and refugees.

Paris fell to the advancing German Army on 12 June and two thirds of France was occupied by 14 June. It became obvious that the French Government in Bordeaux under Marshal Petain were intending to make peace with Germany leaving parts of Western France (Vichy France) unoccupied. The British War Cabinet in London made it a priority to extract forces and other personnel by sea as quickly as possible from the ports of Western France.

Operation Cycle was put in place to carry out an evacuation from Le Havre and despite being hampered by fog and heavy shelling by 13 June over 15,000 troops were saved. Operation Aerial was a much larger undertaking lasting from 15 to 25 June, involving a vast and complicated movement of vessels and the evacuation of thousands of personnel with traffic between many of the ports in western France and southern England. Those which involved the De Gaulle family were Brest and St Nazaire in France and Falmouth in England.

Charles and Yvonne de Gaulle in Hertfordshire, England in the 1940s. Planet News.

Charles de Gaulle, a Captain in the French army, married Yvonne Vendroux on 6 April 1921.

Charles was born in Lille in 1890. His father taught philosophy and literature and Charles was educated in Paris and then began training at the French military academy of San-Cyr to become a professional soldier. In 1913 he joined an infantry regiment commanded by Colonel Philipe Petain and served with distinction and was decorated in World War I. After the War he continued his military career, became a member of the Secretariat of the National Defence Council and began writing and lecturing on military theory.

Yvonne was born in 1900 into a wealthy family in Calais with a background of industrialists and manufacturers. Her father was Chair of the Board of a successful biscuit company. Charles and Yvonne had three children and in 1934 had moved to Colombey les Deux Eglises situated between Paris and the garrisons along France’s eastern frontier. They were living there in 1939 and when war broke out Charles was a Colonel commanding the 507th Regiment of Armoured Tanks in Metz.

Charles had been alert from an early stage to the emerging threat from Germany and was critical of official attitudes and measures taken against that threat. Although it was not a popular view he became increasingly concerned and took an unwavering stand and was at odds with some in government, including Marshal Petain. It was a view that proved correct when Germany marched on Poland and subsequently other European countries and ultimately against France and Britain.

The German advance on France began on 10 May 1940 and by late May De Gaulle had been appointed as an acting Brigadier General. On 6 June he had joined the government of Prime Minister Paul Reynaud as Under Secretary for Defence and War with the brief of liaising and coordinating military action to continue the fight. He flew several times between the French government, by then based in Bordeaux, and London to meet with Winston Churchill who was urging France to remain fighting with Britain after the evacuation from Dunkirk. On his final return to Bordeaux on 16 June he was met with news that this was not acceptable to the French government, that Reynaud had resigned and Petain had become Prime Minister and was preparing for an armistice with Germany.

Charles de Gaulle opposed the plan for the armistice and was in imminent danger of arrest. On the morning of 17 June, he boarded a British aircraft at Merignac aerodrome in Bordeaux flying to Heston airport outside London to continue the fight.

General de Gaulle London 1940. Howard Coster. National Portrait Gallery.

Meanwhile Yvonne de Gaulle was still in France with her children. Philipe was 19, Elisabeth was 16 and Anne 12. As the German army began advancing on France Yvonne and her family together with their nanny, Mlle Marguerite Potel, left their home in Colombey les Deux Eglises. They made their way to Carantec in Brittany arriving on 11 June. Carantec is a commune and seaside resort on the Bay of Morlaix in the Finistere region of North West France. Madame de Gaulle’s sister Suzanne Rerolle had already been there since May with their aunt Madame Richard who had a house there, La Villa D’Arvor.

A present-day view of Carantec in Britanny.

The group moved between houses to avoid detection but on 15 June General de Gaulle drove from Bordeaux to the Brittany Villa to visit his family. He stayed for only half an hour. He told Yvonne that the situation was building towards an Armistice and he might have to leave quickly and alone. The following day Yvonne was visited by two plain clothes men, thought to have been from the Deuxieme Bureau, who gave her passports and money and told her to leave and make for England.

On the morning of 17 June as Charles left France, flying to London, Yvonne travelled with Philipe in a car driven by her sister to seek advice from the British Consulate in the port of Brest. The port was in the process of the full-scale evacuation of troops and personnel by sea. The Consulate advised Yvonne to leave immediately as the window for evacuation was closing. However she returned to Carantec to collect the rest of the family and the next day was driven with them, once again by her sister Suzanne, to Brest.

Leaving her sister behind, Yvonne and her family embarked on the ship the Princess Josephine Charlotte, once a Belgian ship taken into British command by the Ministry of War in early June. The vessel sailed at 16.28 on 18 June, the last to leave Brest as part of Operation Aerial and with the authorities largely unaware of the de Gaulle passengers until they landed in Falmouth on 19 June as the Germans took over Carantec.

British soldiers boarding a destroyer at Brest June 1940 during Operation Aerial. IWM F4813 War Office F Series. Captain Len Puttnam. War Office Official Photographer.

The Princess Josephine Charlotte was launched in 1930 and named for the 3-year-old daughter of Prince Leopold and Princess Astrid of the Belgians. The vessel was registered in Belgium and was part of the Regie voor Maritiem Transport (RMT) the Belgian state-owned Channel ferry fleet. During peacetime the Princess Josephine Charlotte served the Ostend to Dover and Folkstone route with a capacity of 1,400 passengers.

In May 1940 she was used to evacuate Belgian refugees and was then taken over by the British War Ministry and the Admiralty and was used alongside other ferries in Operation Aerial particularly from Brest and St Nazaire. In January 1941 the ferry was converted by Messrs Silley Cox of Falmouth into an infantry assault vessel.

At the end of the War the Princess Josephine Charlotte was handed back to the Belgian authorities and resumed her original purpose as a cross-channel ferry.

Princess Josephine Charlotte in 1941 after conversion to an infantry assault vessel LS142238. IWM A9755 Second World War Admiralty Official : A Series. Lieutenant J A Hampton.

De Gaulle arrived in London in the afternoon of 17 June and met with the Prime Minister Winston Churchill. De Gaulle was not generally well known in Britain but was determined to continue the fight for France and the Prime Minister was supportive of that aim. Churchill was then preparing to deliver the address to the House of Commons the next afternoon which subsequently became his famous “Finest Hour” speech.

De Gaulle wished to broadcast an appeal to German occupied France by the BBC later that day to rally the free French. Initially permission to do so was given but the British government was still negotiating with Petain and there was uncertainty whether the broadcast would take place. However finally, with support from Churchill it was given the ‘go ahead’ to be broadcast. L’ Appel du 18 Juin went out at the end of the 10pm news but was not widely heard by its intended audience and the response in the days following was limited. Unfortunately the broadcast was not recorded.

However when the Petain government in France signed the armistice on 22 June Churchill confirmed De Gaulle’s leadership of the Free French and a second broadcast was made and recorded by de Gaulle that day. By 28 June the Free French position with General de Gaulle as leader was recognised.

During this time, on 20 June, Madame de Gaulle had arrived with their family from Falmouth and joined the General in London.

General de Gaulle broadcasting his message to France from the BBC London 1940. BBC.

After the General’s arrival he asked Churchill that an attempt was made to rescue his family from France. The request was sanctioned and a rescue mission was organised. Captain Norman Hope, a British Secret Intelligence Service Officer (SIS) and a fluent French speaker was sent to the Coastal Command base at Mount Batten, Plymouth to join the crew of an amphibious plane, the Supermarine Walrus L2312. The extent of the mission and its details were kept secret and only the crew would have been briefed. There was a crew of three on the Walrus, consisting of Flight Lieutenant John Bell (Pilot) and Sergeant Charles Harris (Flight Engineer), both from 10 Squadron RAAF, and Corporal Bernard Nowell (Wireless Operator) of the RAF.

Supermarine Walrus being taxied by FO Bell after a flight for carrier retrieval in 1939 Australian War Memorial.

With the four on board the plane took off in foggy conditions in the early hours of 18 June heading for France and Carantec. They crossed the French coast about 20 kilometres west of Carantec but did not reach the destination. The residents of Ploudaniel in Finistere were awoken to the sound of the plane attempting to land in surrounding fields. It is thought the plane had been hit by ground fire and attempting to land hit an embankment and burst into flames. All four on board were killed. Some residents of Ploudaniel took the bodies from the crash site and hastily buried them in the cemetery just before the German advance.

When the aircraft failed to return those on board were posted as missing and in 1941 were presumed killed. Their deaths were not confirmed until after 1946. Their graves remain together in the cemetery where they were buried in Ploudaniel now marked by headstones maintained by the British War Graves Commission.

After nothing was heard from the mission after taking off on 18 June and the failure to return by 19 June a second rescue attempt was made this time by sea. Motor Torpedo Boat 29 was despatched from Plymouth to Carantec on 19 June to discover information about Madame de Gaulle and family’s whereabouts and the fate of the aircraft and crew.

This time the crew of the MTB were accompanied by a Belgian RNVR Officer Van Riel who was the deputy to the missing Captain Hope of SIS. The boat was able to land on 20 June in Carantec but they were forced to leave when they discovered that it was already under German occupation. Although they hoped to land elsewhere along the coast their presence became obvious and they left for England without any further information.

Motor Torpedo Boat, UK, 1943 (D 12524) Copyright: © IWM. Original Source.

Yvonne de Gaulle had made an escape with the family from Brest unaware of these rescue attempts and had arrived in Falmouth just before the second mission set out.

At first there was a need for a headquarters for de Gaulle’s organisation of Free French. De Gaulle was given the use of offices above the jeweller Cartier’s Bond Street premises where he was photographed by Cecil Beaton. After the initial two broadcasts by de Gaulle the response was slow but it gathered momentum after de Gaulle was recognised as leader of the Free French and the Provisional National Committee was set up. As more volunteers began to join in numbers the National Committee used twelve rooms in St Stephen’s House on the Victoria Embankment and later 4 Carlton House became the headquarters of the Free French, now marked with an official Blue Plaque.

Carlton Gardens London during World War II.

The de Gaulle family were reunited in London on 20 June at the Rubens Hotel in Buckingham Palace Road where they stayed after their initial arrival in the capital. The family lived for a short time in Petts Wood in Kent near to London but as bombing attacks increased Yvonne and the younger children moved to Shropshire. When the Germans invaded France Philipe de Gaulle had been a student at the Ecole Navale, the French Naval Academy. After the escape to London he served as a fireman before joining the Free French naval forces in Portsmouth. The period in Shropshire was an isolating time for Yvonne and later the family moved to Little Gaddesdon in Hertfordshire where de Gaulle was sometime able to join them although whilst in London during the week he stayed at the Connaught Hotel. From 1942 until 1944 the family lived together at Frognal House Hampstead.

The flight taken by General de Gaulle to London on 17 June was to have great political significance in the years to come. During the War it was important in terms of the founding of the Free French, in rallying French resistance, contributing to the Allied cause and established the reputation and legend of de Gaulle as a leader. It also established the legacy for the development of both France and Europe in peacetime.

The escape of Madame de Gaulle and family during Operation Aerial highlighted not only the perils of evacuation but the human cost and the real effects of invasion and war.

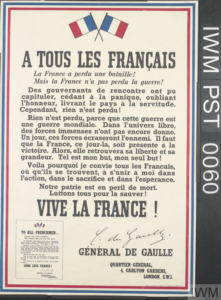

A Tous les Français [To All Frenchmen] (Art.IWM PST 0060)

Copyright: © IWM. Original Source.

The Bartlett Blog is researched, written and produced by volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk