By Linda Batchelor

Falmouth, famous for its harbour, the third deepest natural harbour in the world, has been a safe deepwater port and anchorage for ships since the 1600s. Falmouth International Sea Shanty Festival was founded in 2003 with the mission to keep alive the history of the sea and the days of sail by performing sea shanties, songs of the sea and Cornish songs. It has grown to become the largest free nautical music and song festival in Europe with over 65,000 visitors.

This year the 2025 Festival will take place from June 13 to June 15 in many town and quayside locations with over eighty groups of performers from the UK, Ireland and Europe and elsewhere such as Canada. A glorious celebration of the sea shanty the manual work songs of the age of sail.

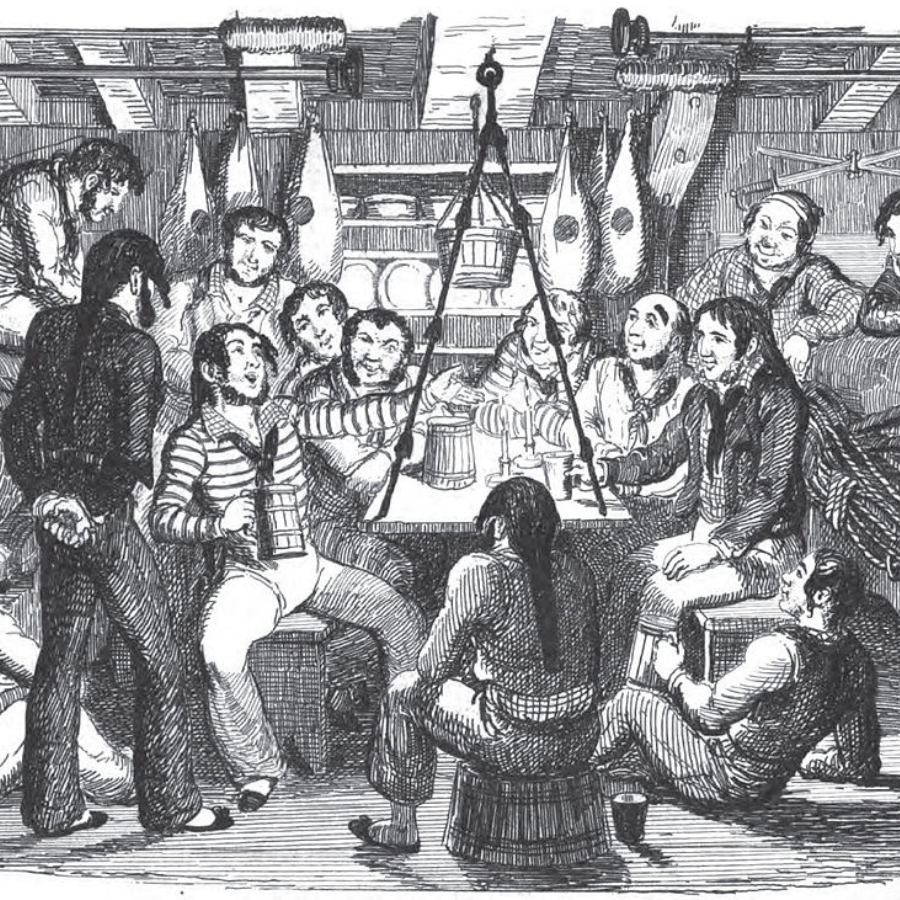

Crowds enjoying the singing in Events Square, Falmouth during the Shanty Festival with the backdrop of the National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

The Shanty

There has undoubtedly always been a tradition of singing at sea, but there is a distinction between sea songs and shanties.

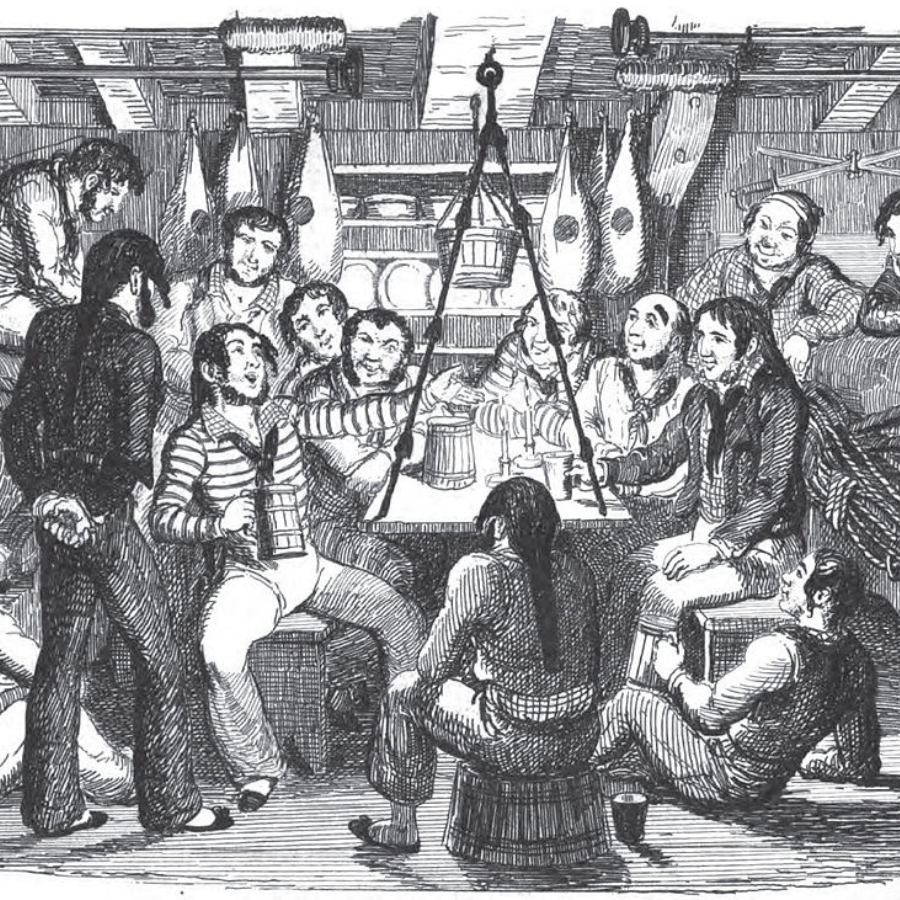

Sea songs came from off duty singing and dancing by sailors known as forebitters or off-watch songs. Fiddlers or flautists were often employed on ships to provide entertainment or accompaniment to singing and dancing to ‘hornpipes, jigs and reels’. In his memoirs James Silk Buckingham the anti-slavery politician, records the story of Joseph Emidy, born in West Africa, enslaved at twelve by Portuguese traders and eventually brought to Lisbon where he became a second violinist of the Lisbon Opera. In 1795 HMS Indefatigable under the command of its Cornish captain, Sir Edward Pellew, was in Lisbon for repairs where he had attended the Opera with some of his officers. They noticed the young violinist with his energetic playing and, in need of a fiddler for the ship, Sir Edward ordered the impressment or kidnap of Joseph, into naval service to “furnish music for the sailor’s dancing”.

Saturday Night at Sea. George Cruikshank (1792-1878). A group of sailors singing. Illustration from ‘Songs, naval and national’ by Thomas Dibdin (1841).

Shanties were work songs aimed at co-ordinating the manual labour for the many tasks required in sailing a ship. These songs (chants) of a repetitive nature not only provided rhythm, regular breathing patterns and synchronized movement but also encouraged a sense of unity of effort in collective physical duties.

References to these type of work songs can be traced from the mid 1400s with origins in many cultures. However the English term ‘shanty’ or ‘chantey’ in North America, probably came from the French ‘chanter’ to sing. It only began to emerge in a maritime work context from the eighteenth century and reached its heyday in the early to mid-nineteenth century.

The Categories of Shanties

The categories of shanties fall into the two main areas of working a ship under sail and are classed as capstan or halyard songs or alternately as heaving or hauling songs. Heaving songs such as “Spanish Ladies” were used in manning a capstan for raising weights or using pumps while hauling songs, for example “Drunken Sailor”, were for the essential work of raising and lowering sails and pulling ropes. They have a strong rhythm and a steady beat to help with the gruelling nature of the work but while capstan work required longer sustained effort, halyard work required a different effort with a pull and relax rhythm

Shanties often have a ‘call and response’ format with the call being made by a lead singer or shantyman and the other sailors responding with a chorus or refrain. The shantyman was a regular sailor who would take the lead. Sometimes the shanty man would make impromptu additions to verses. Some became well known for leading and were a valuable asset to a crew.

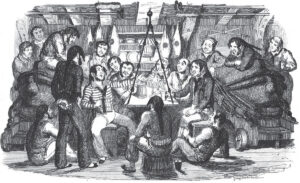

Heaving the Capstan on an East Indiaman with a fiddler is providing music for the task. Illustration from ‘The Quid – Tales of my messmates’ by W. Strange 1832.

One of the oldest examples of a heaving or capstan shanty “Spanish Ladies” was recorded in the logbook of HMS Nellie in 1796. The shanty describes the homeward voyage of a Royal Navy warship from Spain to the Downs in England. During the War of the First Coalition (1793 – 1796) against France British ships were supplying Spain and many sailors had Spanish wives, lovers and children who were not allowed to accompany them home. The shanty reflects this and also describes the various landmarks passed on the voyage, including the ‘Deadman’ or Dodman in Cornwall, in its verses and repeated chorus.

Farewell and adieu to you Spanish Ladies,

Farewell and adieu to you ladies of Spain.

For we received orders for sail to Old England,

But we hope, very soon, we shall see you again

Chorus

We’ll rant and we’ll roar like true British sailors,

We’ll rant and we’ll roar along the salt seas

Until we strike soundings in the Channel of Old England,

From Ushant to Scilly is 35 leagues.

Although the reference for this shanty comes from a Royal Navy source they were mainly sung on merchant vessels. On naval vessels shanties had limited use and capstan work was usually accompanied by fife and drum or fiddle or by bosun’s pipe.

“Drunken Sailor” dates to the early 1800s and was one of the few shanties allowed and sung at the time in the Royal Navy. It was used for halyard work and hauling up boats.

What will we do with a drunken sailor (x3)

Earl-eye in the morning.

Hooray and up she rises (x3)

Earl-eye in the morning.

The preferred method aboard naval ships was for as little noise from those on duty with only the officers allowed limited speaking. There were periods when shanty singing was banned for the sailors in the Navy. This was the case, especially on heavily manned and crowded warships, so that commands could be clearly conveyed.

On merchant vessels where arduous tasks were achieved with fewer sailors and where crews were of a more individual nature the use of singing was of considerable advantage in coordinating work and the shanty flourished. Shanties were used extensively on a variety of British, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and American ships.

“South Australia” is a rousing shanty from ships engaged in the maritime supply trade to and around Australia.

In South Australia I was born,

Heave away, haul away,

South Australia, round Cape Horn,

We’re bound for South Australia.

Ships varied from small to large merchantmen, packets and clippers, whalers and East Indiamen, traversing the oceans and seas carrying a huge range of cargoes, passengers and emigrants or engaged in certain activities.

“Roll Down” is an example of a shanty sung on fleets transporting emigrants to Australia.

Sweet ladies of Falmouth we,re saying goodbye.

The Development of Shanties

There were many influences both cultural and musical in the development of shanties. In some instances such influences came from shore-based practices to a maritime context but many shanties were written at sea, directly influenced by the working practice of a ship under sail or of a crew’s experience. An important factor was that the tune and the wording could be easily remembered and that the rhythm of the shanty matched the task in hand.

The origins for these shanties came from many sources. Folksongs and ballads and other popular songs were one major source and sometimes hymns. Working chants were also another source. Sailors had long had a tradition of chants for short burst tasks called ‘singing out’ or ‘yo-hoing’ which came to be incorporated into some shanties. Other working chants which had influences came from labourers engaged in particular tasks on land and, especially in North America, from loggers and lumberjacks and those loading cotton.

Shanties covered a whole range of subjects from historic to contemporary and the mood could be tragic or sentimental or humorous and often bawdy. Sometimes shanty verses reflected contemporary events and sometimes were a way of airing particular complaints about conditions or even other members of the crew, including the captain.

The shanty “A Drop of Nelson’s Blood” refers to the fact that after Nelson’s death at Trafalgar his body was preserved in brandy for the voyage back to England. Afterwards the Navy rum ration for sailors was often referred to as ‘Nelson’s blood’.

Oh a drop of Nelson’s blood wouldn’t do us any harm

And we’ll all hang on behind.

The Demise and Revival of the Shanty

As sail gave way to steam many of the tasks required on a sailing ship were able to be done by mechanical means and the need for actual manpower diminished. Without the impetus of providing the rhythm of call and response the use of the shanty was no longer essential and it became negligible during the first half of the twentieth century. Despite its demise as a practical work tool shanties were kept alive by veteran sailors and folk song collectors.

In the early 1900s the Australian composer Percy Grainger recorded the singing of shanties on wax cylinders and in 1905 Sir Henry Wood introduced his “Fantasia On British Sea Songs” at a Promenade Concert to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar. The shanty “Spanish Ladies” is included alongside a “Sailor’s Hornpipe Jack’s the Lad”.

In 1914 Cecil James Sharp of the English Folk Song Society published ‘English Folk Shanties’ in which he recorded the lyrics and tunes from retired seamen. After the First World War during the 1920s there was a revival of interest in shanties both in Britain and the Americas. In the late 1920s the American James Madison Carpenter collected shanties from Britain, Ireland and the North-Eastern United States. In mid century William Main Doerflinger published his book ‘Songs of the Sailor and the Lumberman’ in the United States which included shanties from New York and Nova Scotia recalled by retired sailor Patrick Tayluer. In Britain in 1961 Stan Hugill, sailor and folk music artist, published his definitive volume “Shanties of the Seven Seas’.

Interest in shanties has continued to grow and many versions of shanties have been made by various recording artists. One of the recent ‘hits’ on social media has been the singing by Nathan Evans of “Soon May the Wellerman Come”. The song from about 1830 takes its name from the ships of the Weller Brothers whose vessels supplied New Zealand whalers.

There once was a ship that put to sea

The name of the ship was the Billy O’Tea

The winds blew up, her bow dipped down

Oh blow, my bully boys, blow (huh)

The popularity of the rendition of the song is an indication of the continuing interest in sea songs and in shanty singing. The Falmouth International Sea Shanty Festival is thriving proof of this interest. Enjoy!

The Bartlett Blog is researched, written and produced by volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk