Explore the remarkable connections between Falmouth’s deep harbour, its influential residents, and the exotic plants that still flourish in Cornwall’s world-renowned gardens today, in this Bartlett Blog.

By Linda Batchelor

Robert Shuttleworth Sutton was a Packet Service Captain from 1797 until 1835 and had commanded HMP Windsor Castle from 1814 and HMP Stanmer from 1817. Both packet ships regularly sailed the route to Brazil and in November 1832 the Stanmer had sailed via Madeira, Tenerife, Pernambuco, Bahia and Rio de Janeiro to Brazil. Captain Sutton, from Flushing near Falmouth, was credited by the Royal Cornwall Horticultural Society as a keen horticulturalist and it not surprising that like many of his contemporaries he was interested in collecting examples of plants from places he visited on his voyages. On the voyage to Rio in 1832 he had found a plant growing in a wood on a sloping hill near the Bay of Bonviago, Rio de Janiero, dug it up and brought it home. On his return to Falmouth in March 1833 he had presented this example and a “choice collection of orchidaceous and other interesting plants he had found” to Sir Charles Lemon of the Carclew estate near Mylor and Mr George Croker Fox of Grove Hill House in Falmouth. Both men were influential figures in Falmouth and Cornwall, Sir Charles, as an MP and wealthy landowner and Mr Fox as the head of the firm of leading ship agents in Falmouth. Their commercial interests were widespread including shipping and mining but they also had interest in science, botany, horticulture and gardening.

In 1837 The Royal Cornwall Horticultural Society recorded in its Annual Report that the Society’s Silver Medal was “presented to Captain Sutton, formerly of HM Packet Service, as a tribute of acknowledgement for the zeal he has evidenced in the promotion of Horticulture, and many of the new and rare species he has introduced to the country.”

These instances illustrate the interest in plant collecting. Not only the development of economic botany but also of ornamental horticulture and the part played by transporting plants around the globe often by voyages at sea.

Built by the Fox family in 1789 with panoramic views of the harbour and the sea and extensive grounds. It was a much-loved family home for around 150 years with gardens renowned for exotic plants.

Plant Collecting

Plant collecting and the introduction of species between environments has a long history throughout the world. Sometimes the introduction of plants to a new environment has been driven by necessity, trade, conquest or exploration and also by curiosity, scientific interest, profit and prestige. Early examples in Britain are the introduction of saffron by Phoenician traders to the South West and the introduction of many plants by the Romans. At a later stage in history the creation of gardens and landscapes by the owners of landed estates led to the acquisition and cultivation of a wide range of ‘exotic’ plants.

The development of plant collecting grew gradually in Britain due to all the factors involved and it began to assume botanic and horticultural importance in the 17th century. The distinction between economic botany and ornamental horticulture also began to emerge. Economic botany is driven by the need for the provision of utilities such as food and fodder and the requirements for fibres, medicines and chemicals. Ornamental horticulture is concerned more with aesthetic values and sometimes has been the means of displaying wealth and power. These categories are not exclusive although it was the latter which gave momentum to the development of plant hunting in the 18th and 19th centuries. Britain’s growing power at sea and of empire also contributed to the expansion of scientific and social interest in botany and horticulture.

The West of England and particularly Cornwall and Falmouth were geographically well placed in this respect. Falmouth was established as a new town after the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 and received its Royal Charter in 1661. With its deep natural harbour, good anchorage and easy access to the south-western approaches the town flourished, especially after being chosen as a packet station for the Post Office Packet Service in 1688, it rapidly became established as a major port.

There were already early existing trade routes by sea between Cornwall the Mediterranean and the Levant and the packet service opened more, first to Corunna in Spain and Lisbon in Portugal followed by those to the Caribbean and the Atlantic ports of North and South America. Falmouth became the first and last port of call for many ships, both British and foreign vessels. “Falmouth for orders” became a phrase which reflected the importance of the harbour and the town in the growing expansion of the sea routes for trade, travel and empire.

As these connections grew so too did the interest in flora and fauna from abroad both locally and nationally. This was especially true in communities where there was a connection with the wider world such as Falmouth with its widespread maritime links. This interest was also reflected in the country in general by the establishment of a variety of societies and by voyages of discovery and expansion.

The Development of Learned Societies

In November 1660, following a lecture given by Christopher Wren, a fellowship was formed concerned with natural philosophy. As the Royal Society for the Improving of Natural Knowledge it received its royal charter from Charles II to “transform knowledge, profit and the conveniences of life” through scientific development and experimentation.

Botanic gardens with documented collections and scientific purpose were first developed in Italy at Pisa, Padua and Florence in the mid 1500s and used in the training of medical students. The concept spread to other parts of Europe in Germany, France and the Netherlands later in the century. The introduction of bulbs from the near East to Holland led to the cultivation and development of the tulip trade. Other such gardens opened in Paris and European cities and capitals.

In Britain the Oxford Botanic Garden opened in 1621, the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh in 1673 and the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1673. Kew was first established as a botanic garden by Princess Augusta, mother of George III, in 1759. Now a world centre for plant genetics Kew received seeds from the expedition Joseph Banks (1743-1820) undertook with Captain Cook on HMS Endeavour to the South Seas. On his much-feted return to England in 1771 Banks, a passionate naturalist, became Kew’s unofficial director.

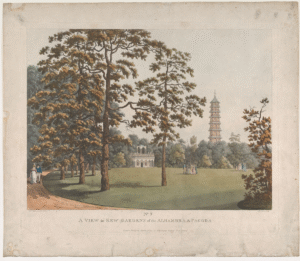

View of Kew Gardens in 1798. Franz Joseph Manskirch. Aquatint Heinrich Joseph Schutz Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As maritime trade increased and the empire grew so too did the flow of plants to these gardens and in 1804 the Royal Horticultural Society was founded. In Cornwall the Royal Cornwall Horticultural Society was founded in 1832 with “an interest in exotic plants unmatched by other societies”. This was followed in 1833 by the Cornwall Polytechnic Society.

Maritime Expeditions

There were many notable expeditions by sea, particularly during the 18th and 19th Centuries, to undertake surveys, explore new territories, develop shipping routes, investigate scientific theories, test nautical equipment and to expand knowledge of fauna and flora. Many were in Royal Navy ships but also there were privately funded voyages. Ships of HM Packet Service and of the East India Company (East Indiamen) were also involved in transporting seeds and plants from overseas territories to Britain. Ships usually carried a surgeon on board, often with an interest in the natural world, and expeditions also sometimes included civilian scientists, naturalists and observers.

The Expedition of HMS Endeavour Royal 1769. Royal Mail First Day Cover.

The voyage of HMS Endeavour (1768 -1771) to the South Seas was one such expedition to observe the Transit of Venus but also with secret orders to explore the lands in the Southern Ocean and to claim territory for the British government. The expedition was commanded by Lieutenant James Cook with a naval crew and they were joined by Joseph Banks and his accompanying party. Banks had already been part of an earlier expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He was a wealthy Lincolnshire landowner with a serious interest in science especially in botany. He financed his part of the expedition and was accompanied by several servants, two artists to record findings and a companion and fellow naturalist Daniel Solander. The return of the expedition was a geographical botanical and zoological success. Cook had claimed part of the East coast of Australia for Britain and Banks and Solander returned with over 30,000 botanical and 1,000 animal specimens.

Sir Joseph Banks painted in 1773 on his return from the expedition of HMS Endeavour Joshua Reynolds. NPG.

Another voyage was made by HMS Discovery under Captain Vancouver which charted the Pacific coast of North and South America accompanied by Archibald Menzies who ‘discovered’ the Monkey Puzzle tree.

The 1831-1836 voyage of HMS Beagle under Captain Fitzroy with Charles Darwin also involved momentous scientific discoveries and arrived in Falmouth on its return to England. On arrival at Falmouth Darwin left immediately but Captain Fitzroy dined with the family of Robert Were Fox at their home, Penjerrick and presented them with a brain coral from the expedition.

Prominent Figures

The study of science and the natural world developed and was encouraged in Britain by the growth of these related societies and institutions and by these voyages of discovery. The expansion of empire, emerging technologies, industrialization and the increase in wealth not only amongst the landed class but in the middle classes all added to this development. In many respects Cornwall was at the forefront of such development especially regarding its maritime advantages and its mining expertise with a number of prominent figures involved in the study of aspects of science especially in botany and horticulture.

Members of the Fox family of Falmouth were such an example. Robert Were Fox was part of the wealthy Quaker Fox family, well known in Falmouth for running the shipping business of G.C. Fox & Co founded in 1762 and with interests in the Perran Foundry, mining and fishing. As well as his commercial interests Robert was a scientist of some distinction, inventor of the Dipping Needle, a Fellow of the Royal Society and a gardener. His home Penjerrick historically and horticulturally became one of the most important gardens in Cornwall. Other members of his extensive family in the Falmouth area also developed their gardens and it is no coincidence that with their shipping connections these gardens contained specimens from many parts of the world.

Robert’s children, Barclay, and his sisters Anna Maria and Caroline were all also engaged in intellectual enquiry. In 1833 the sisters founded the Cornwall Polytechnic Society ”to promote the useful and fine arts, to encourage industry and to elicit the ingenuity of a community distinguished for its mechanical skill”. Two years later it became the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society when it received its Royal Charter.

Other examples in Cornwall of those with scientific and horticultural interests who contributed to plant collecting were John Hawkins (1761-1841) of Trewithen and Sir Charles Lemon (1784- 1868) of Carclew and Miss Elizabeth Warren of Flushing.

John Hawkins of the Trewithen estate near Probus was an intellectual of independent means. He was an author, traveller and linguist with a deep specialist knowledge of geology, minerology, botany and natural history. He travelled extensive on the Continent and in the late 1700s had accompanied John Sibthorp on his plant collecting tour of Greece. After Sibthorp’s death he was responsible for the publication of Flora Graeca the illustrated record of the collecting tour. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society, a founder member of the Royal Horticultural Society, a member of the Geological Society of London and of the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall.

Sir John Hawkins (1761-1841). Richard Cosway.

Sir Charles Lemon (1784 -1868) the owner of Carclew, a large estate between Mylor and Falmouth was another patron of science and horticulture. He was extremely wealthy, a mine owner, MP for Penryn and later for West Cornwall and with considerable influence in Cornwall and the towns of Truro, Falmouth and Penryn. He too was a Fellow of the Royal Society, President of the Royal Statistical Society, the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall, the Royal Horticultural Society Cornwall and the Cornwall Polytechnic Society. With his head gardener William Booth he developed the gardens and grounds at Carclew receiving exotic specimens and seeds from abroad via various sources including Captain Sutton of the Packet Service and from the Sir William and Sir Joseph Hooker the directors at Kew. He was one of the first to receive and grow rhododendron seed at Carclew.

As an unmarried financially independent woman the amateur botanist Elizabeth Andrew Warren (1786-1864) was a somewhat different contributor to the study of Cornish flora. She was born in Truro into a family with a background in mining and farming backgrounds. She spent part of her early life in Kent but aged thirty seven she returned to live in Flushing close to Falmouth where her botanical work began in earnest. Her circle included local gentry and MPs, other botanical collectors both within and outside Cornwall and those serving in the navy and in the packet service of Falmouth. Her own study was concentrated on seaweeds from around the Fal but her circle also gave her access to more exotic species. She stated that “I am in the habit of receiving plants and corals from all over” and she maintained a professional correspondence and the mutual exchange of seed and specimens for twenty five years with Sir William Hooker of Kew. She was a founder member of the Royal Polytechnic Society in Falmouth and a contributor to the Royal Cornwall Horticultural Society.

Obtaining Specimens

Specimens and seeds from abroad came to Britain by sea particularly through the major ports of which, with its major maritime trade connections and fast communications, Falmouth was one. The Packet Service, the Royal Navy, ships of the East India Company and a whole variety of merchant vessels used the port and attracted a diversity of travellers and was a conduit for importation of many goods including plant specimens. There was increasing demand for these imports both nationally and locally at both an official and private level. Although many of the importations went through London and other ports such as Southampton there are many examples of such arrivals in Falmouth. The great gardens of Cornwall all benefitted including those of the Fox family.

Captain Kempthorne of the Packet Service is recorded as bringing plants home from Jamaica on his voyage in HMP Antelope in 1793. Captain Sutton also of the Packet Service was a prolific donor of plants from the Caribbean and South America to Sir Charles Lemon and the Fox families. Plants and seed specimens were also often sent to Kew and other institutions on Falmouth packet ships from expeditions such as HMS Beagle.

Captain Sulivan of the Royal Navy was from Flushing and throughout his naval career sent plants to Falmouth to local collectors and national institutions from the places his ships visited, including South America and the Falkland Islands.

Plants and seeds also came to Falmouth via the Captains of East Indiamen again going to local collectors such as Miss Warren but also sent on to various institutions such as Kew.

John Rule, a Mine Captain from Camborne was Superintendent of the Real del Monte Mines in Mexico, 1823 -1842. He travelled to Mexico from Falmouth with Cornish miners contracted to work in the silver mines. Over his time in Mexico Captain Rule sent seeds and numerous bulbs, roots and plants to Cornwall collectors via the Falmouth packets to Lady Basset, Mr Pendarves and Sir Charles Lemon. He retired to Penzance in 1842.

Plant Hunting

As plant collecting grew it sparked greater scientific study and led to more organised plant hunting. These plant hunters were sent on dangerous missions, subject to shipwreck, piracy, disease and injury. They became not only major figures in the botanic and horticultural world but sometimes public heroes.

Sir Joseph Banks is described as “the father of modern plant hunting”. After his early expeditions with Captain Cook he had returned to acclaim and a position at Kew Gardens where he developed the idea beyond just collecting plants to the specialised study of plants. He also realised the economic potential of adapting plants from one environment to another. He began the practice of sending specialist collectors around the world. It was Banks who encouraged the expedition on HMS Bounty under Captain Bligh to deliver breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the West Indies which also led to the mutiny.

Bread Fruit Plant. Watercolour prepared by the artist Sydney Parkinson on board HMS Endeavour 1769. Natural History Museum.

Other institutions, such as the Horticultural Society of London and sometimes government agencies sent plant hunters around the globe for scientific and economic purposes such as the ‘capture’ of tea from China to India. Commercial nurseries developed and also employed plant hunters.

John Veitch, a Scottish gardener, arrived in Devon in 1771, employed by Sir Thomas Acland to landscape the gardens at his estate at Killerton outside Exeter. By 1808 with the encouragement of Sir Thomas he had established his own nursery business there which he ran with his son James who took over the nursery in 1837. James was one of the first to pioneer exploration and sponsor plant hunters for commercial purposes during the golden era of plant hunting. The first hunters for the nursery were William and Thomas Lobb from Cornwall.

The brothers were part of the family of John Lobb who was employed in 1831 as a carpenter by Sir Charles Lemon of Carclew. William and Thomas both started work for Sir Charles in his gardens and stoke houses and both were encouraged by him when they showed an aptitude in raising plants being brought to the gardens and developed an interest in botany.

William (1809 -1864) also worked as a gardener for various other estate owners in the Falmouth area until by 1840 he had been recruited by James Veitch as a plant hunter for the nursery. William’s first expedition, 1840-1844 was to South America. He was given training at Kew of how to preserve seeds and plants and left Falmouth on HMP Seagull for Rio de Janeiro and first explored in Brazil before moving on to Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador and Panama. He returned from there having collected a vast amount of material for the nursery but also some privately for Sir Charles Lemon and others of his previous employers.

He undertook subsequent expeditions to South America in 1845 – 1848 and to North America 1849-1853. He collected examples of many species of plants but especially of trees such as the Monkey Puzzle and the Wellingtonia and of numerous bushes and shrubs all of which were grown from seeds at the Veitch nurseries and which became commercially available. After the date of his last exploration he remained in California, it appears as a freelance hunter. His health deteriorated over the years and he died in San Francisco in 1864.

Thomas (1817 – 1894) had also been employed by Veitch and had recommended William as their first plant hunter. Thomas undertook four exploration trips 1843 – 1857. He was sent first to the East to Java, Singapore, Penang and Malaysia. Subsequently he went to India, the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines. He collected examples of orchids and rhododendrons which became commercially available through Veitch. He injured his last trip which led to amputation. He left Veitch’s employment in 1860 and retired to Stanley Villa in Devoran, Cornwall to be near to family and to garden and paint. He died in 1894 and is buried in the churchyard there.

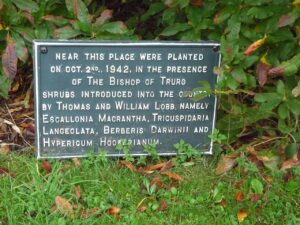

Memorial plaque in Devoran Churchyard, Cornwall to Thomas and William Lobb.

Transporting plants

Transporting seeds and plants to Britain by sea from distant parts of the globe was a hazardous business. This was true for seeds but particularly so for live plants. In the 1770s Joachim Loddiges (1786 -1846), a London nurseryman, noted that only one in twenty plants survived the journey by sea from North America. John Livingstone (1770-1838), a surgeon for the East India Company in China was a keen horticulturalist who collected Chinese plants and sent examples to London in the early 1800s. In a paper written for the Horticultural Society of London he estimated that only one in a thousand would survive on voyages from China.

John Ellis (1710- 1776) became the most successful plant transporter of the 18th century. He was an Irish linen merchant in London and a colonial agent for the British government for West Florida and Dominica. He had botanical and horticultural interests which included assisting colonial farmers in America to benefit from plants from elsewhere and a scientific approach to plant transportation. He published several works on natural history such as “Directions for bringing over seeds and plants from the East-Indies and other distant countries, in a state of vegetation”. This contained information for “Captains of Ships, Sea Surgeons and other curious Persons who collect Seeds and Plants in distant Countries”.

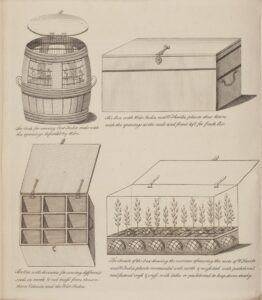

Illustration for packaging seedlings for shipment by sea from Directions for bringing over seeds and plants from the East-Indies and other distant countries, in a state of vegetation. John Ellis 1770.

The length of voyages could cause problems for transporting specimens as well conditions on board ship, lack of water or light, shipwreck or the restrictions and hazards of war at sea.

Over time several methods were adopted for transporting seeds such as covering them in beeswax or wrapping them in paper and packing them tightly in sealed tins. Ellis suggested that seeds from certain plants could be planted in a wooden box divided into squares which were filled with earth and moss. The box could then be nailed shut and some seeds would germinate during the voyage. Although seeds were dry commodities this was not a guarantee of preservation on a voyage. Seeds might dry out, rot or be attacked by pests such as weevils. Ellis recommended the use of corrosive substances like sulphur and mercury should be distributed in or painted onto the boxes to deter insects.

In some respects, therefore it was preferable to send live plants despite the greater possibility of loss. Live plants were packed in casks or barrels with holes bored in the side or in sealed boxes with air vents. On some plant collecting expeditions large areas of a ship were given over to plants, the case on expeditions by Joseph Banks and the breadfruit expedition of HMS Bounty. On commercial vessels transport conditions could be hit or miss for successful preservation. Problems arose if plants were kept below decks without light of sufficient water and above deck they could be affected by salt spray, storm or excessive heat.

The answer came with the development of Wardian cases.

The Wardian Case

Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward was a doctor in East London in the 1830s. His invention of the Wardian case, a sealed timber and glass case transformed the survival of plants on long sea voyages. It kept the plants safe from the elements but let in light and moisture. Ward had struggled to grow ferns in the soot and smoke of East London until he developed a sealed mini greenhouse to protect them and realised that it might also solve the problem of transporting live plants by sea.

Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward 1866 RHS Lindley Library

As an experiment Ward sent two of his cases to Australia filled with British ferns and grasses and after the voyage the ship’s captain wrote to offer his “warm congratulations” that the contents were alive and flourishing. On the return voyage around Cape Horn the cases carried Australian plants which arrived in similar condition having only required watering twice during the voyage.

Replica Wardian cases on display on the weather deck of SS Great Britain 2024

Ward was in correspondence Sir William Hooker of Kew Gardens and published a book “On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases” in 1847 by which time the cases were in regular use by Kew. In 1843 Joseph Hooker had used them for the expedition to circumnavigate Antarctica to successfully send plants home to Kew from New Zealand. Also in the 1840s the plant hunter Robert Fortune had used them to smuggle 20,000 tea plants from China for the British government to establish tea plantations in Assam in India.

The cases revolutionised the transportation of plants, contributed to the golden age of plant hunting and introduced a myriad of new plant species to Britain and across the world. They were used by many different institutions and on many sailing ships but with the advent of faster transport and of storage conditions other means of plant transportation gradually took over. Kew used them until 1962.

They also played a part in the development of British gardens, including many in Cornwall, both great and small. Fittingly one of the oldest existing original examples of these cases is on display in Cornwall’s largest private botanic gardens at Tregothnan, an estate and gardens upstream from Falmouth on the banks on the River Fal.

The Bartlett Blog is researched, written and produced by volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk