By Linda Batchelor

In the age of sail one of the most important roles on board ship was that of the Sailing Master.

Masters were highly skilled specialists responsible for the navigation of the ship, for log keeping and charting and, in some situations, could take command of the vessel. Over time the distinction developed between the naval and the merchant services giving rise to changes in the designation and status of Masters but their importance remained crucial in sailing a ship.

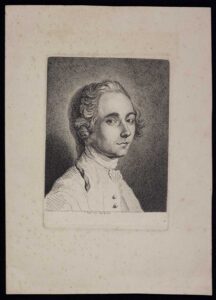

Bligh as Master of HMS Resolution. John Webber. William Bligh c.1776. National Portrait Gallery of Australia. Purchased with funds provided by the Liangis family 2015.

During the Middle Ages in England there was no established navy. When there was a need for naval operations merchant ships were hired for service for the purpose. In such situations there was a distinction between the terms of master and captain with the Master of the merchant vessel controlling the ship and its mariners whilst a Captain was in command of embarked soldiers.

It was not until 1546 that Henry VIII established a permanent fleet of fighting ships, administered by a Navy Board, as a national navy. After 1660 during the reign of Charles II the navy became the Royal Navy. The importance and strength of the navy grew as Britain built its dominance as a major sea power. In 1707 after the Union with Scotland the navies of England and Scotland were amalgamated and by the end of the century the Royal Navy was at peak efficiency with manning levels of over 145,000 men. From the outset the permanent navy began to use skilled professional sailing masters responsible for sailing and navigation and initially often drawn from outside the service. By the seventeenth century this position was designated as a Royal Navy rank of Master which existed until abolished in 1867.

Alongside the development of the Royal Navy as a fighting force the merchant services also grew as foreign trade expanded, territorial ‘discoveries’ were made and empires expanded. It was in this mercantile context that the position of professional sailing master had initially developed. Traditionally on merchant ships the owner or person commanding the ship, the crew and the cargo was known as the Master. The term Captain was often used as courtesy title and in many instances in ocean going merchant ships the captain would also have a sailing master who was responsible for navigation and pilotage and who could command in some circumstances.

In the Royal Navy warrant officers represented areas of expertise required aboard ships, such as surgeons, shipwrights, boatswains and sailing masters. Masters were the highest ranking non-commissioned warrant officers. They were highly skilled in navigation with the most prestige of the rank and were classed as Wardroom Officers with the privilege of access to the wardroom and the quarter deck. Whilst officers, such as Lieutenants and Captains, received commissions from the Admiralty in the name of the Sovereign, Warrant Officers were appointed by warrants issued by the Navy Board.

To receive their warrants they were required to take an oral examination which was a practical assessment of their abilities in navigation and seamanship. The examination was conducted by Trinity House with a panel consisting of a Royal Navy Captain and three well qualified and experienced Masters. The candidate for prospective master also had to produce a character reference or certificate from ‘good substantial people’ of a ‘sober life and conversation’.

Although Masters were ‘officers’ with some of the privileges of rank they were not of the same status as commissioned officers who came from the gentleman class. Masters were drawn from various backgrounds particularly the merchant service where they gained their knowledge and experience before joining the navy whilst others had risen through the ranks.

James Cook 1759 as Master of HMS Pembroke by Thomas Major, Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand. Major, Thomas, 1720-1799. Artist unknown : [James Cook]. T. Major sculpt. Reg. Cap. 1759. Various artists :[Profile, half- and full-portraits of Captain James Cook, including one of him as a young man, as well as a number of depictions of his death at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii. 1759-1880, 1925]. Ref: A-451-001. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/30645484

James Cook became Master of HMS Pembroke in 1757 having joined the Royal Navy two years previously. From 1746 he had served an apprenticeship on Whitby colliers owned by the Walker brothers, enlightened Quaker ship owners who encouraged him to study mathematics and navigation. In their employ for nine years he had acquired considerable experience in both the coastal and ocean-going trade and served as a sailing master on several of their ships. In 1755, having joined the Royal Navy as an Able Seaman he had taken his examination at Trinity House in June 1757 and by October of the same year was appointed by warrant as a Master.

Often they also came direct to Royal Navy service from the more middle levels of society with lesser social standing, particularly from seafaring related backgrounds. William Bligh for example was the son of a Plymouth customs officer whose name was first entered for naval service as a boy as a Captain’s Servant in 1762 and who officially went to sea in 1770 as an Able Seaman before being rated as a Midshipman. Bligh passed his lieutenant’s examination in 1776 but was not immediately commissioned but was appointed to serve as Master to Captain James Cook on Resolution.

A few candidates came via the Greenwich Upper School which in the early nineteenth century provided education and naval training for the sons of lower ranked officers of the Royal and merchant navy. By 1841 there was the opportunity for high achieving pupils to be selected by examination for specialised training at the Greenwich Nautical School. The Headmaster Edward Riddle FRSA was the author of a Treatise on Navigation and

Nautical Astronomy (1821). Those selected received professional instruction in navigation, nautical astronomy, the use of nautical instruments, chart drawing and marine surveying and were externally examined by Trinity House. There was an annual government award of appointments to eight of the highest achieving students as Master’s Assistants in the Royal Navy. Daniel Pender born in Falmouth in 1832 descended from seafarers and officers in the Packet Service was one such candidate. He was appointed in 1847 as Master’s Assistant on HMS Acheron which sailed to undertake the survey of the coast of New Zealand. It was the beginning of his naval career as a surveyor and hydrographer initially as a Master eventually rising in rank to become Assistant Hydrographer of the Navy.

The Officers of HMS Plumper on Survey in Canada of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. Master Daniel Pender seated second left. British Columbia Archives.

In the naval hierarchy Masters were ranked below naval Lieutenants although above Lieutenants commissioned into the Marines. They were classed as Wardroom Officers with the privilege of access to the wardroom and the quarterdeck alongside the commissioned officers and Masters had their own cabin and an office for pursuing their work. It was Masters who were responsible sailing a vessel and who were not only expert in navigation but also in hydrographic surveying and charting which became part of their remit.

Like Captains they did not generally stand watch but were on call twenty-four hours a day and were often the most highly paid officer on ships of the line apart from the Captain. Masters were assisted by and in command of Master’s Mates and junior Warrant Officers. The duties were demanding, including navigation, recording the official log, pilotage, plotting courses, hydrographic surveying and charting, inspecting sails, rigging and anchors, instructing Midshipmen in navigation and responsibility for stowage and ballast and the security and issue of beer and spirits.

Before 1748 naval officers did not have a designated uniform but wore their own contemporary clothing. Marines had a uniform from the 1660s but it was not until 1748 after naval officers petitioned the Admiralty for official dress that the first uniform pattern was issued which included dark blue frock coat and white waistcoat which resembled upper class contemporary male dress. This uniform was for commissioned officers only and was issued to distinguish their rank as gentlemen. Although Warrant Officers were not designated a uniform they would have usually worn their own versions of naval dress until they were given a standard official plain dark blue uniform 1787. In 1805 Masters were given a distinctive uniform to reflect their senior Warrant Officer status.

Henry Roberts Osborn RN of Falmouth in Master’s Uniform c1830-1840, Artist Unknown, National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

The position of (Sailing) Master remained as a naval rank until the latter half of the nineteenth century when some ships were no longer beginning to be powered by sail but by steam. In 1867 the rank was abolished and replaced by commissioned officer rank of Navigating Lieutenant.

Masters in the Merchant Service

In the mercantile service the term Master was used in several contexts. It was the title of the person who was the owner or person in charge of the vessel and who could also be known as the Captain. The Master or Captain was usually an experienced seaman with the skills to command the vessel and its crew and with a knowledge of sailing and navigation. Captains in the merchant service were sometimes recruited as (sailing) Masters by the Royal Navy for their experience in command and navigation.

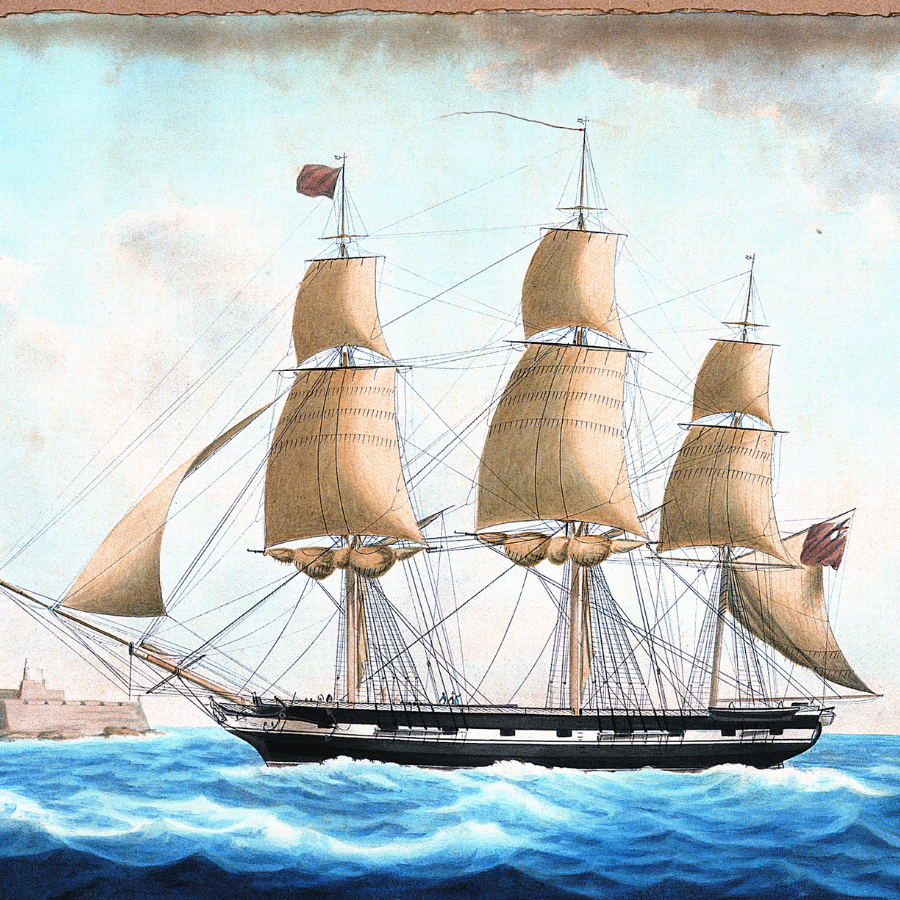

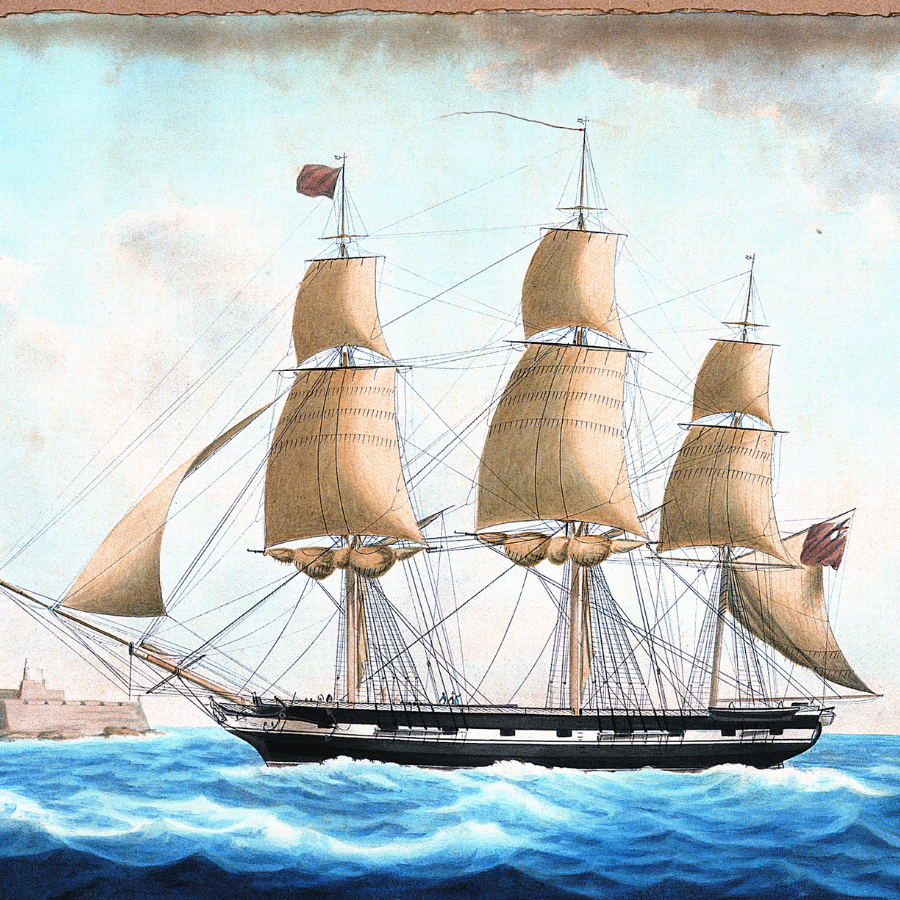

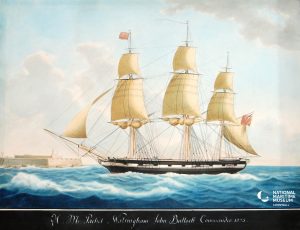

The Captain of a merchant vessel would command with the assistance of a Mate and frequently on a major ocean-going vessel he would also do so with the help of a Sailing Master. This was particularly the case in the Falmouth Packet Service with its designated and demanding routes and sailing timetables where the position of the Sailing Master was an important one as a senior member of the crew who was responsible for navigation and capable of taking command if necessary.

His Majesty’s Packet Walsingham, Nicholas Cammillieri (1773? – 1830), copyright National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

An example of this occurred on the voyage of the Packet Anna Teresa when the Captain and owner of the vessel Edward Lawrance died at sea off Martinique on a sailing to the West Indies. The Packet was brought home to Falmouth by her Sailing Master John Gaylard.

It was also common practice for the Captain of a packet to sometimes remain on shore in Falmouth whilst the Sailing Master took the ship to sea on one of its regular sailings. In 1807 William Rogers the Sailing Master of HMP Windsor Castle was in temporary command of the ship. William had joined the Packet Service aged seventeen in 1795 and had become Sailing Master of Windsor Castle in 1804. The vessel was owned and commanded by Captain Sutton on regular routes from Falmouth to North America and the Leeward Islands but for this voyage Captain Sutton had remained in Falmouth with the Sailing Master in command. On approaching Barbados the packet was attacked by the heavily armed and much larger French privateer Le Jeune Richard. William Rogers and his crew fought bravely against greater odds to repel the attack. Finally after several hours of hard fighting Rogers and five of his uninjured crew boarded the privateer, tore down her colours and drove the surviving crew below decks forcing their surrender and took Le Jeune Richard as a prize. Captain Rogers and his crew returned to England as heroes where they were financially rewarded from a large public subscription fund.

William Rogers of HMP Windsor Castle, Samuel Drummond (1766 – 1844), NMMC, On loan from National Maritime Museum Greenwich.

Captain Rogers was awarded several swords of honour and promoted by the Post Office as commander of a new packet The Countess of Chichester. The action was also commemorated by a painting by Samuel Drummond exhibited at the Royal Academy which together with the artist’s bust length portrait of William are on display in the National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

An example of presentation swords on display at National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

Certification of Masters and Mates in the Merchant Service

Despite the continuing growth of the merchant service throughout the centuries state involvement in the service was limited and resisted by many ship owners. In the mid eighteenth century Masters or owners of most British registered ships were required to complete Muster Rolls recording details of the crew and the voyage to be registered before leaving port but there was no official scheme for the competency of Masters and Mates until the mid-nineteenth century.

Prior to 1845 qualification for merchant officers was not formalised and generally a position at sea relied on practical experience regarding seamanship and gained knowledge of navigation and charting. Sometimes this would be via an apprenticeship at sea or from private schools of navigation. This was the case for James Cook who was apprenticed in 1746 to ship owners in Whitby, who encouraged his nautical studies resulting in his being well qualified when he joined the Royal Navy in 1755 and progressed quickly to the rank of Master on HMS Pembroke.

During the nineteenth century the need for the merchant service to be commanded by competent officers became more obvious following several disasters at sea and public pressure for action grew. In 1836 a Select Committee on Shipwrecks was set up under the MP for Sheffield, James Silk Buckingham, a Cornishman born in Flushing. The Committee produced its report within a few months which criticised the competence and navigational skills of some mercantile masters and senior officers. Recommendations were made including the establishment of a Marine Board and examinations and certification for senior officers.

Initially no action was taken by Parliament but public concern continued and after considerable delay in 1845 a voluntary scheme for certification as a Master or a Mate was introduced by the Board of Trade. An examination of candidates proficiency in seamanship and navigation was to be conducted by Trinity House. Fees for the exam were modest at £2 for Masters and £1 for Mates. Candidates had to be over 21, be able to write a legible hand and be able to use a sextant and a chronometer. They also had to provide evidence of good character and sobriety. The scheme gained credence slowly but gradually it began to be valued and the 1850 Marine Act set up compulsory examinations of officers in British registered ships in the foreign trade. The Marine Department was also set up in the same year and in 1854 with the Mercantile Shipping Act it became compulsory to have a certified Master in passenger ships in the home trade although not for those in coastal trade which came much later.

Legacy of the role

As sail gave way to steam the role of the Sailing Master on both Royal and Merchant Navy ships changed and ultimately became an obsolete title. Nevertheless despite technical changes and advances in skills, technology, and qualification there is still an underlying need for the experience, competency and skills of the Sailing Masters of the past in the present day.

Further Reading:

Maritime Views

Transcription of the Journal of Captain Lawrance of the Anna Teresa

A Very Nice Middy Daniel Pender 1832 -1891

Bartlett Blogs

The Journal of Captain Edward Lawrance

The Bartlett Blog is researched, written and produced by volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk