By Linda Batchelor

On the maiden voyage of RMS Amazon, in January 1852, the wooden paddle steamer caught fire off the Isles of Scilly. The inquiry that followed transformed shipbuilding standards across the empire.

On 5 January 1852 William Stone, Fourth Engineer of the steamship Amazon sent a letter to Mr George Mills, the Chief Engineer of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company.

“Dear Sir, I am very sorry to inform you that the Steamship Amazon caught fire about 1’O Clock on Sunday morning in the Bay of Biscay, burnt to the water’s edge and went down.”

‘The Times’ also reported that the Royal Mail Packet Steamer Amazon had been “totally consumed by fire” 100 miles off Scilly. The catastrophe on the vessel’s maiden voyage to the West Indies, carrying fifty passengers, one hundred and fifteen crew, mail and cargo valued at over £100,000, was described by the Company Directors as “a most appalling accident”. Of those on board the Packet over one hundred were lost in what was a major maritime disaster. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were at the forefront of an appeal, contributing an initial £150, for the support of the widows and orphans of those lost. The tragedy engendered huge public sympathy and the appeal subsequently raised £12,000.

Later in January that year flotsam from the wreck washed up at Falmouth. Today a figurehead in Falmouth is a feature of Upton Slip overlooking the harbour. The National Maritime Museum Cornwall is situated on discovery Quay in Falmouth and Upton Slip, a narrow ope or alleyway, is close by leading from the main street down to the harbour. Here, affectionately known as ‘Ami’, is the large female figurehead reputed to have come from Amazon which has adorned the waterfront for many years and is a reminder of the disaster.

The Figurehead ‘Ami’ in Upton Slip, Falmouth

The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company

The Amazon, launched in 1851, was a coal fired wooden paddle steamer, the first of five steamers commissioned by the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company.

The Post Office Packet Service was a branch of the Royal Mail established to carry international mails and government dispatches. In 1688 Falmouth located at the south western approaches to the British mainland and with advantageous sea links became an important Packet station and terminus port for the international mail service. Initially serving Spain and Portugal, by 1705 there was also a regular service to the West Indies and the Americas.

The Falmouth Packet Service was under the control and management of the Post Office until 1823 when it was taken over by the Admiralty. After this change of control the Falmouth Packet Service faced increasing competition from commercial companies, between sail and steam and the gradual move of the mail services away from Falmouth to other ports such as Liverpool and Southampton with larger dock facilities and direct rail links.

In 1837 the Peninsular Steam Navigation Company (later P&O) obtained a contract for a weekly steamer service carrying the mails from Falmouth to Spain, Portugal and Gibraltar. The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, established in London in 1839, secured a contract with the Admiralty in 1840 to provide a fleet of not fewer than fourteen steam ships to carry mails twice monthly from Southampton calling at Falmouth to the West Indies, Mexico and Cuba. This was the beginning of the end for the Falmouth Packet Services and in 1851, when the last of the sailing packets the Seagull returned to Falmouth from Rio, after one hundred and fifty years of service the Falmouth Packet Station was closed.

The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company commissioned their fourteen wooden paddle steamships from 1840. They were all named after rivers associated with their shipbuilders, and the fleet was known collectively as the West India Mails. It was noted in a local Falmouth newspaper that “the West Indian Company give the preference to seamen paid off from her Majesty’s packet service” and that command of the Severn, the last of the fourteen new ships to be built, was to go to Mr William Vincent who “from his boyhood belonged to the packet establishment at this place” (Falmouth). Although the first of those fourteen ships the Thames had left from Falmouth on 1 Jan 1841 the Company had designated the home port for the ships as Southampton.

RMS Severn in the Bristol Channel. Joseph Walter (1783-1856) The Postal Museum

Alongside the PSN Company the RMSP Company pioneered the new steam technology with its advantages of increased speed, power and comfort but the technology was often challenging in operation and expensive. In its first decade the RMSP Company suffered considerable loss of ships and sometimes loss of lives. According to the London Evening Standard 8 January 1852 “Shortly after the establishment of the company, there appeared to be a strange fatality attending its success”.

Nevertheless the demand for steam travel continued to grow and by 1850 the Company had ordered five new paddle steamers of which the Amazon was the first and largest of a new fleet of five sister ships.

RMS Amazon

Amazon was built by the firm of R & H Green of the Blackwall Yard on the Thames in London.

The yard was first opened in 1614 and passed into the Green’s ownership at the end of the eighteenth century. The yard was famous for its sailing frigates built for the Royal and merchant navy. It was not adverse to innovation building its first steam ship in 1821 and its first paddle steamer in 1834 but although there was a move towards iron hulled ships in accordance with Admiralty requirements the RMPS Company elected to have its five new ships built in wood.

Amazon was laid down in 1850; built of wood she was a three masted barque of 2,256 tons and with a length of 300 feet. The vessel was equipped with both sails and engines with two paddle wheels in external boxes, one on either side and two funnels. The two side lever engines were built by Seaward & Capel of Limehouse London providing 800 horse power and a top speed of 15 knots steam powered. When launched in 1851 Amazon was the largest side wheeler ever built and proceeded to Southampton in December for the start of the ship‘s maiden voyage to the West Indies.

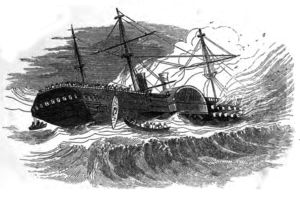

Royal Mail Steam Packet Company Ship Amazon leaving Southampton on her maiden voyage. Illustrated London News 1852.

The ship carried the Mails, cargo and fifty passengers. The majority of the passengers were male but also on this maiden voyage there were also several female passengers accompanying their husbands and with at least one single female passenger. Some passengers were returning home to the West Indies and Mexico whilst others were going for business or to take up employment or government posts

There was a large crew of one hundred and twelve required for servicing the sails and the engines and providing facilities for the crew and the fifty passengers. Several in the crew were from Cornwall, particularly Falmouth, and had served or had connections with the Packet Service there. They included the commander Captain Symons, the Second Officer Mr Treweeke, Mr Vincent one of the Midshipmen and William Fox a ship’s boy. A passenger also from Cornwall was Lieutenant Charles Grylls of the Royal Navy, son of the Vicar of St Neots, who was going to join his ship HMS Devastation in Jamaica.

Captain William Symons was an experienced mariner described in reports as “one of the ablest company officers” and “who in long conduct of difficult navigation had never met with the slightest accident”. He had previously served in the Packet Service and on both the Peninsular Steam Navigation Company and lately the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company ships. He had commanded the PSN vessels Tagus, Braganza and Montrose in the Mediterranean and by 1845 was in command of RMSP Clyde serving Mexico and the West Indies. He was destined for appointment as commander of the Orinoco, sister ship of the Amazon. Command of Amazon was to go to Captain Chapman but he was not available for the maiden voyage and as Orinoco was not yet completed Captain Symons had been provisionally appointed to the Amazon.

William Symons Master’s Certificate of Competency – Issued 1850 in Southampton

The Marine Act 1850 required certification of officers on British ships in the foreign trade.

In the enquiry following the disaster it was also reported that “all the officers, engineers and crew of the Amazon were picked men and were selected for appointment to the new ship for their previously known abilities and intelligence.” Despite the experience amongst the officers and many men in the crew the ship had been rushed into service to meet deadlines and the crew had not been given thorough instruction into some aspects of the new technology or time to ‘bed in’ the new vessel.

The Maiden Voyage

Amazon left the New Docks at Southampton at 3.30pm on 2 January with an admiring crowd both on the dock and in accompanying vessels on the water and proceeded down the Channel running at a speed of 8 Knots. As with all new engines the bearings often run hot until the engines get into trim and in this case the overheating in the engines required the Amazon to hove to twice for several hours at night on both 3 and 4 January. There was apprehension of fire amongst some of the passengers and crew in this respect but most of the passengers and the crew had retired to their beds after the engines had been cooled and restarted on the night of the second stoppage on 4 January. By then the ship was a hundred miles off Scilly running before the wind at a rate of 12 to 13 Knots in a developing gale from the South West.

At about 12.40 pm fire broke out below decks. It was later reported by Mr Neilson one of the surviving passengers that “in less than ten minutes it was bursting up the fore and main hatchways”. Mr Treweeke the Second Officer as Officer of the Watch was on the bridge which was between the paddle boxes with Mr Vincent, the Midshipman. Mr Treweeke raised the alarm and sent for Captain Symons who immediately came on deck and began steps to fight the fire. By this time the passengers were alerted and with the fire filling the decks below with flames and smoke were driven onto the main deck some half clothed and in distress to witness the frantic efforts to stem the rapid spread of the fire with water hoses and buckets.

By now the flames were reaching high above the funnels and the decks below were filling with smoke. The fire had reached the tar and tallow store below decks and flames shot high above the funnels isolating the bridge and cutting off communication between the two ends of the ship. Captain Symons asked for the engines to be stopped but the engineers despite heroic efforts had been driven out of the Engine Room by intense and suffocating smoke and it became impossible to stop the engines or use the water pumps. The ship continued to be driven forward by the unstoppable engines and the increasing gale. The bales of hay kept for the livestock on the main deck caught fire and the forward lifeboats were already on fire.

Amazon on Fire. From ‘Sorrow on the Sea, An Account of the Loss of the Steamship Amazon by Fire’ 1852

Amazon was equipped with nine boats, unusually for the times sufficient for the ship’s complement but some were lost early to the fire. The boats had also been fitted with iron crutches to hold their keels steady on the deck but the crew had not been sufficiently instructed in how to free them which hindered attempts to launch them. When the remaining boats were released the lowering was still difficult with the speed of the ship and the rising wind. Many of those in the boats being lowered at uneven angles were flung into the sea or the boats were swamped by the waves and most drowned, as were all the twenty five lowered in the Mail Boat. Some survivors managed to regain the boats or cling on. Mrs McLennan holding her eighteen-month old son was left clinging to the gunwale of one of the boats, remaining until it was righted when all others had been flung out. Eventually only a few survivors escaped in the boats and the ship’s small dingy.

The contemporary descriptions by survivors of the desperation of the situation and the furious nature and rapid spread of the fire are harrowing. Many on board had already died in their berths, been suffocated or burned to death before the ship sank. At about 4am the masts collapsed and when the two magazines exploded at 5am the ship, with the funnels glowing red, went down. As the fire consumed the ship over a hundred passengers and crew including Captain Symons were lost.

Survivors

First reports were that there were only twenty-one survivors who had been rescued by the brig Marsden of London. Sixteen of the survivors had escaped Amazon in a starboard lifeboat and five more had been picked up after half an hour after launch by the lifeboat from the dingy. The total included passengers Mr Neilson and Mr Sisley and the rest were crew including William Vincent, Midshipman, who had been in the dinghy with James Williamson, the Chief Steward, two seamen and Mr Sisley.

On being taken into the lifeboat William Vincent, the 18-year-old son of Captain Vincent of RMSP Severn, assumed command of the lifeboat and his gallant conduct was reported by those on board and later in ‘The Times’ it was stated that “Mr Vincent who though a mere boy in years proved himself a thorough man and a sailor.” In a letter to the Board of Trade and the Directors of the RMSP Company one of the rescued passengers Mr Neilson wrote of the Midshipman that “not for one moment during the trying scene which followed did the young officer show the slightest symptom of fear or hesitation … his entire conduct throughout was worthy of the profession to which he belongs.”

Silver Gilt Presentation Pencil and Case. From Thomas Sisley to Mr William Vincent As a mark of sincere Esteem and Regard January 4th 1852. Photo: Bonhams.

The lifeboat using William Vincent’s jacket on an oar as a sail was making towards the French coast when picked up at noon on Sunday by the Marsden under Captain Evans sailing from Cardiff to North Carolina with a cargo of railway iron. At first the boat was taken under tow and then the survivors were taken on board the brig where they were afforded every comfort by the Captain and his crew and the ship’s course was altered to land them in Plymouth at 10.50 p.m. on 5 January. They were accommodated at the Globe Hotel overnight and in the morning Mr Vincent and Mr Neilson left by train to report the loss to the Company whilst the crew were taken care of by the Shipwrecked Mariners Society.

Meanwhile it was reported that a further seven passengers and eighteen crew had been picked up in two boats by the Dutch galliot the Gertruida and landed at Brest. They had been given help by the Captain and his crew and were landed at Brest. Among the survivors was Mrs Eleonor McLennan and her young son who had been travelling to Demerara with her husband who was lost and Miss Anna Maria Smith from Dublin who was travelling to take up a post as a governess in Costa Rica. The two women had showed remarkable endurance and had encouraged other survivors and on arrival at Brest they were cared for by the family of the British Consul. All the survivors were then repatriated via Morlaix.

On 16 January a further thirteen survivors including Lieutenant Grylls, three other passengers and nine crew were landed at Plymouth. They had escaped in a port lifeboat and were adrift at sea for some days under Lieutenant Grylls’ command until picked up by another Dutch ship the Hellechina eventually making her way towards the Channel. The survivors were transferred to the British Revenue Cutter HMS Royal Charlotte off the Dodman and taken to Plymouth.

The Inquiry

An Inquiry into the disaster and its causes was set up by the Directors of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. The Board of Inquiry was held on 17 January and the Board was made up of the Directors, Company members such as George Mills the Engineer in Chief of the Company and senior Captains from the Company including Captain Chapman who should have been the Commander of the Amazon. Other officials concerned were the Superintendent of Southampton Packet Service and Captain Walker from the Board of Trade.

Statements and eye-witness accounts were taken from survivors from both passengers and crew. William Vincent Jnr’s account was given prominence as were the accounts from Mr Stone the Fourth Engineer, Mr Allen the foreman of Seaward and Capel who had been on board, various crew members and Lieutenant Grylls. Passengers testimonies came from passengers on each of the boats such as Mr Neilson, Mr Sisley and the Reverend Blood.

Evidence was considered from various sources as to the cause of the disaster. Various factors were identified and considered. They included the ferocity and speed of the fire, the overheated bearings with the need and methods of cooling, the debris left by the builders in spaces below decks in the last minute rush into service and the flammable nature of the large amount of pine used in the construction of the ship. There was also consideration of the insufficient familiarization of the crew and engineers with the vessel in general, the equipment and the technology which added to the confusion in the emergency of the fire. It was as one contributor stated “a miracle that anyone had survived”.

The ultimate conclusion was that no one factor was solely responsible for the devastating conclusion and loss of life but that all factors had made a contribution to the outcome. No direct blame was attached to the “appalling accident” but recommendations were made for safety features of future development projects. The Company suffered severe losses whilst the disaster appeal raised an enormous amount of funds which sought to alleviate the effects of the loss to the families of the passengers and crew. However, the disaster served as a terrible reminder of the effects of fire at sea especially in wooden ships. The Admiralty also altered its policy regarding future mail ships and began adopting requirements for iron hulls.

The Bartlett Blog is researched, written and produced by volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk