By Denise Davey

When Denise Davey joined the new Maritime Museum in Falmouth as a volunteer, the Museum was under construction and the library was in its infancy. The book collection, of which six or seven thousand were donated by John Bartlett, grew rapidly with more donations and loans from other libraries and now amounts to over twenty thousand volumes held in the Museum’s Bartlett Library. In time the collection has come to include periodicals, leaflets, flyers, research, charts, videos and CDs. The need for access to this unique and valuable collection led to the design of BART, a search programme developed by Denise and Jonathan Griffin with other members of the volunteer team in the Bartlett Library. In this article Denise describes that development.

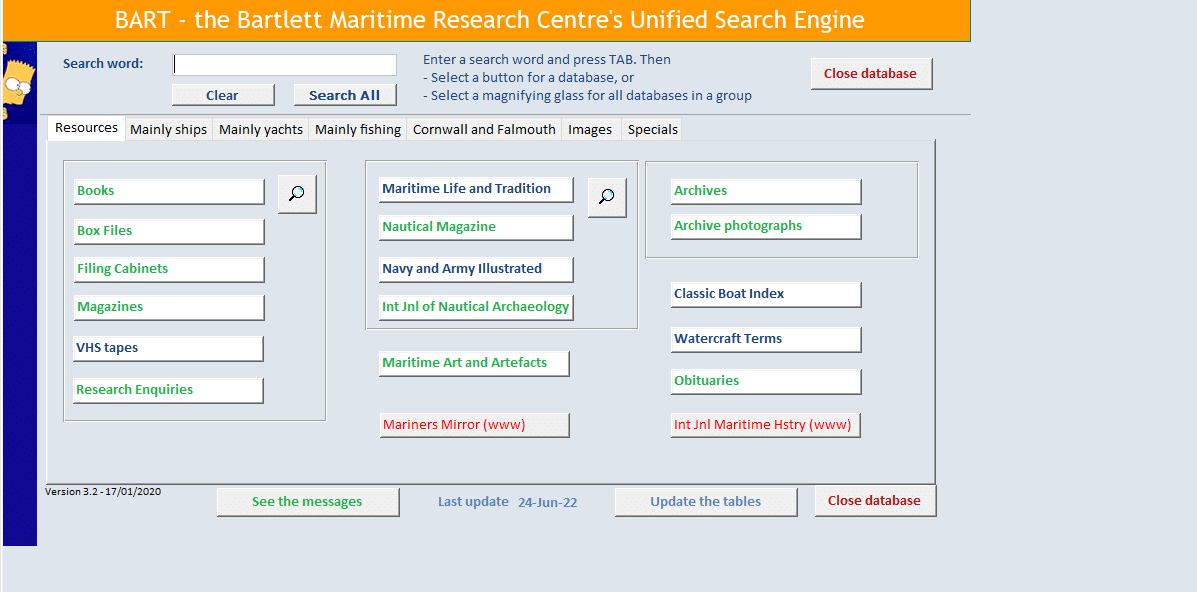

BART, the Bartlett Maritime Research Centre’s Unified Search Engine.

The Early Days

The scarlet factory doors of the unit on Tregoniggie industrial estate were not the sight I had expected when I volunteered for the library of the new maritime museum in Falmouth. A shore-side boatshed with nets and crab pots maybe? Inside, the scene was even more incongruous. A series of trestle tables were piled high with books being sifted through, passed around and sorted into other piles by a team of volunteers, like an academic jumble sale.

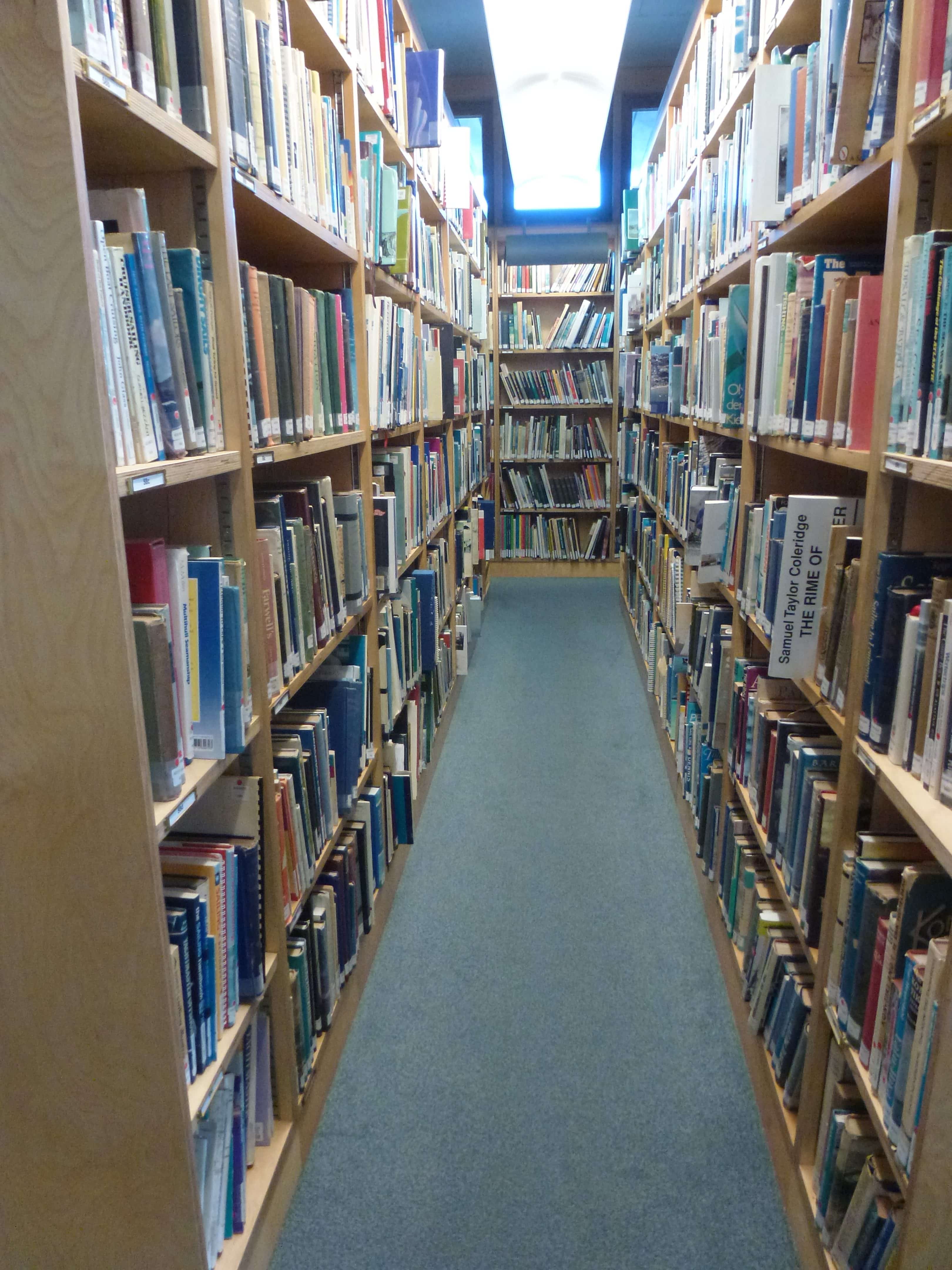

By the time the museum was built and we had moved into our current premises, the books had gained a rudimentary sort of grading, and shelving. Keith Haddon had begun describing and cataloguing them back in the industrial unit, but the system was inadequate for the task of accessing a specific book amongst the six or seven thousand donated by John Bartlett. A more professional approach would be essential. Added to this, loans were made available by other libraries, donations of books and artefacts were coming in from well-wishers, all of which needed to be tracked. We were very fortunate in having available the skills of a chartered librarian in Sue, who has painstakingly classified each book in our collection, now amounting to some twenty thousand volumes.

The Collection

The collection came to house not just books but periodicals, leaflets, flyers, research, charts, videos, CDs. Many volunteers spent countless hours compiling databases of information culled from sources available to us – all of which needed to be accessible to the volunteers working in the library to assist the public in conducting their research. Research work completed on behalf of members of the public by library volunteers was not to be done and forgotten. There needed to be a way of knowing what was there and how to reach it for future reference.

Part of the Book Collection in the Bartlett Library and Research Centre.

The Development of BART

Writing this, I am conscious of finding ways of expressing the concept of “access” without being repetitive. However, that was, and is, the main driver behind devising a search programme such as BART. We knew very early on that it would become necessary for all of us to be able to put our hands on any item held within the library and the Haddon Reading Room as quickly as possible. It seemed like a description of life, the universe and everything …

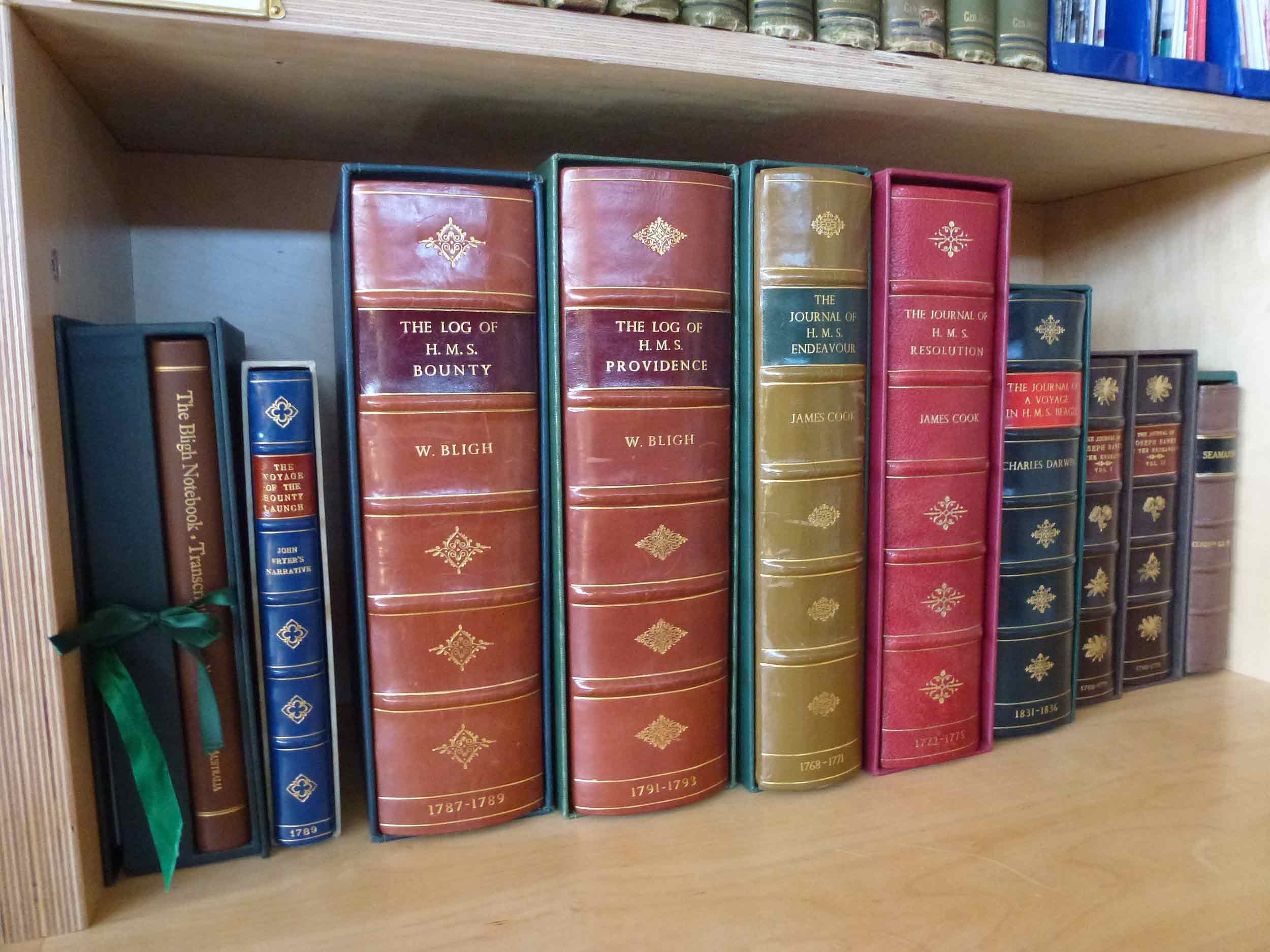

Books on display in the Haddon Reading Room.

Luckily, Microsoft came to our aid. Seemingly, we were not the only enterprise that needed to be able to keep track of large numbers of entities. By 2003, Anne had acquired some new computers from BT and at that time computers came complete with Microsoft Office as standard. Within that suite of software, along with Word and Excel, was Access, a graphically intuitive creator and manager of relational databases.

Prior to that, we had been using the MSDOS level software known as DB3 to create our databases. This was far less intuitive for the novice computer users amongst our volunteers. Poor Keith had spent many, many frustrating hours attempting to train us (with varying degrees of success) to use DB3 and correcting the countless mistakes that had ensued.

The data painstakingly entered into DB3 could be directly imported into Access, so all was not lost when we switched over, and progress could be made straight away. Our then Director of the Museum, Jonathan, was (and is) a complete techy and keen to get involved to improve the efficiency of the library.

The Database

A database had been set up to handle the catalogue of books, including details of each book’s provenance, physical size and location and Jonathan swiftly made this more sophisticated and speedy.

With Doreen, I had become involved in keeping track of the filing system with its sundry collection of papers, cuttings, correspondence, reminiscences and general flotsam. A number was allocated to each piece. When the volume of items on a particular topic grew too bulky to be held in the filing cabinets, they were transferred to box files and shelved, again each with an identifying number. Both systems also had their own database.

The magazines held in the Haddon Reading Room in the Library were many and varied, with incomplete runs and sometimes amalgamated one with another. In order to fill in the gaps of the runs we needed to keep track of our holdings, so another database was born.

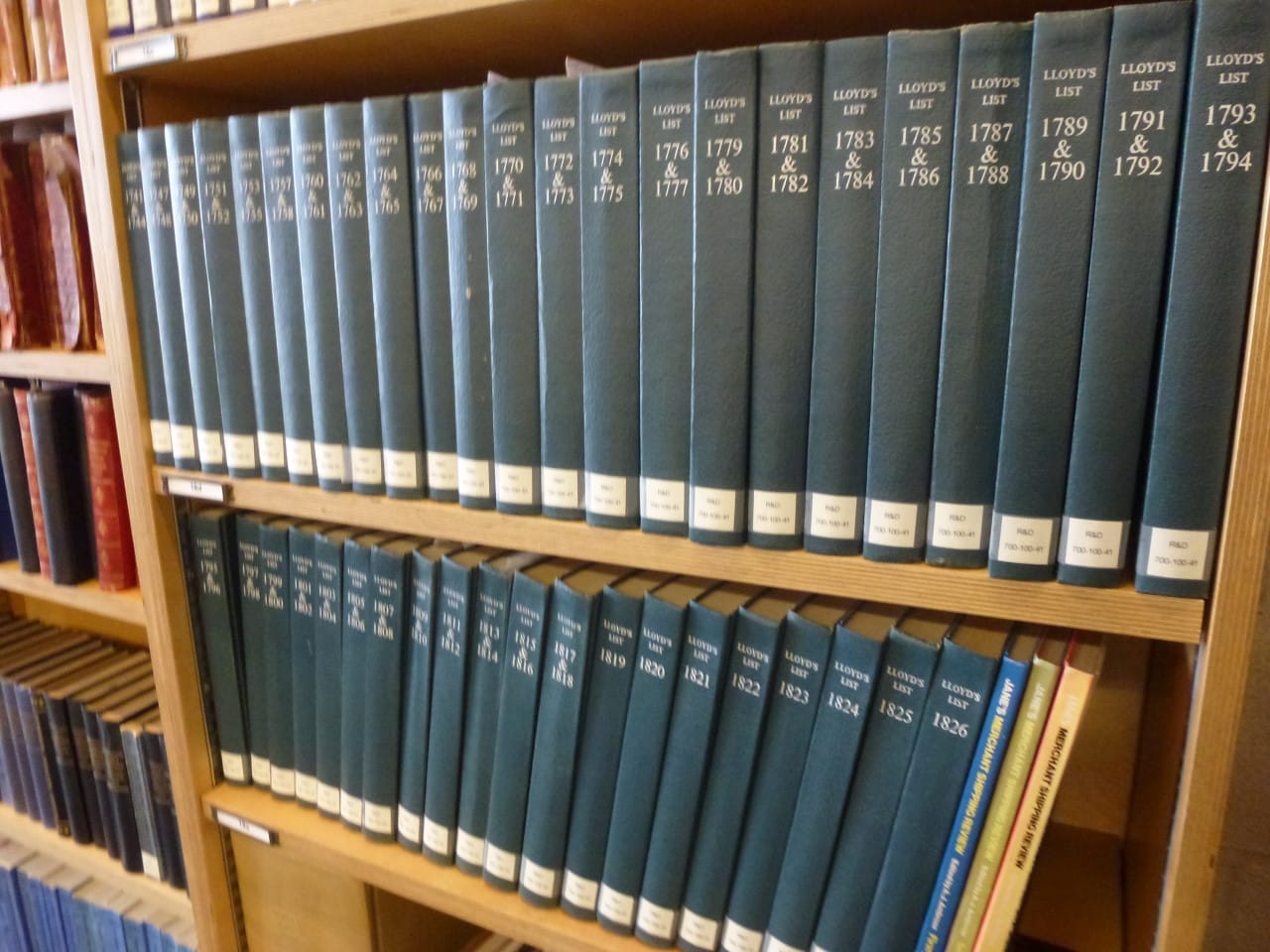

Research done by volunteers compiling information extracted from journals held by us was entered into databases. For example, Eleanor’s Lloyds List data showed vessels entering Falmouth throughout the years as published in Lloyds List with details of their passage; Derek had listed the boats in the NMMC collection alongside references to magazines articles, from which we formed the basis of the Design Index that we are still using today.

Volumes of Lloyd’s List have provided data entry now also listed on BART.

As more volunteers worked in the library, pursuing personal interests and research projects, so the databases proliferated. In order to benefit from all that work and wisdom a way was needed to bring them all under one data roof. This was the bread and butter of a relational database. The idea is that one over-arching database is able to control a series of others by querying each one as to what it contains. It does not hold all the data, it simply asks the others “What have you got for me?” The response is all that is necessary to find the information that we need, be it the location of a book about Henry Scott Tuke or what articles have been written about laser dinghies and in which magazines.

Cue our techy. Jonathan was well informed in the arcane ways of relational databases and how to code them to work speedily. We had been using a very “belt and braces” form of Access database to provide a platform for the Catalogue, the filing system and the magazines, but now Jonathan was able to bring together so much more. In no time at all he had integrated the work of others into the system showing just physical resources. Over the years this has come to include the Archive held by the museum at our Ponsharden site, copies of photographs held by us, images by Colin made available to the Museum and listed by Jo, and much more.

Continuing Access

And it is growing all the time. Whenever we process a research enquiry on behalf of the public, we keep details of the work carried out. This will be digitised and made available on our library network for further reference – accessed on our screens by way of BART. We can find information in our system on ocean shipping lines, Polynesian navigation, cod or Newlyn, in the form of a book, an article written in 1932 or a CD of Master Mariners and Mates.

Isn’t that remarkable?

The Bartlett Blog

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. BART in Pursuit of Access was written by Denise Davey.

The Bartlett Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.