By Linda Batchelor

In October as part of National Maritime Museum Cornwall’s 2024 Autumn Lecture Series, Dr Charlotte Mackenzie will be telling the remarkable story of Mary Broad/Bryant. This Blog examines the contemporary story of John Arscott, a convict from Truro in Cornwall, and Catherine Prior, an accomplice of Mary Broad, who were both sentenced to seven years transportation and taken to Australia on board the First Fleet.

Convicts Embarking for Botany Bay, Thomas Rowlandson (1756 -1827). National Library of Australia.

Until the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 convicts sentenced to be transported had been mainly sent to North America but this solution was no longer possible. Faced with the courts continuing to issue sentences for transportation and adding to the overcrowding in British gaols in 1776 the Government authorised the use of derelict ships or hulks as a means of providing extra prison accommodation. The Government also began to consider alternative solutions as to where to transport prisoners, but it was not until 1785 that the destination was finalised.

In 1770 Lieutenant James Cook, Captain of HMB Endeavour, together with his crew had been the first Europeans to chart the East coast of Australia. In his journal entry for 22 August Cook recorded that he and a party from the ship had landed, at what is now known as Botany Bay, and “In the name of His Majesty King George the Third took possession of the whole of the eastern coast down to this place by the Name of New South Wales together with all the Bays, Harbours, Rivers and Islands situate upon such coast”. It should be noted that New South Wales had been inhabited for 40,000 – 60,000 years before the arrival of the British. In 1785 it was to this coast and the territory of New South Wales that the British Government announced that convicts sentenced to transportation would be sent in the future.

Thomas Townsend, Lord Sydney, the Secretary of State for the Home Office, had decided to establish a penal colony and settlement at Botany Bay. The idea had been advocated by Sir Joseph Banks and others who had accompanied James Cook on the first voyage of HMB Endeavour. The original purpose of the expedition had been to observe the Transit of Venus and to search for the Great Southern Continent, but the expedition had also circumnavigated New Zealand, charted the East Coast of Australia and claimed the territory of New South Wales for Britain. For Lord Sydney the decision to set up the colony in Australia in an area already claimed by Britain had two purposes, to challenge French expansion in the Pacific and to provide an outlet for the transportation of convicts.

John Arscott and Catherine Prior from Cornwall, both sentenced to seven years transportation, were part of the First Fleet and the first settlement in Australia at Port Jackson. John and Catherine travelled from England on convict transport ships, John on Scarborough and Catherine on Charlotte.

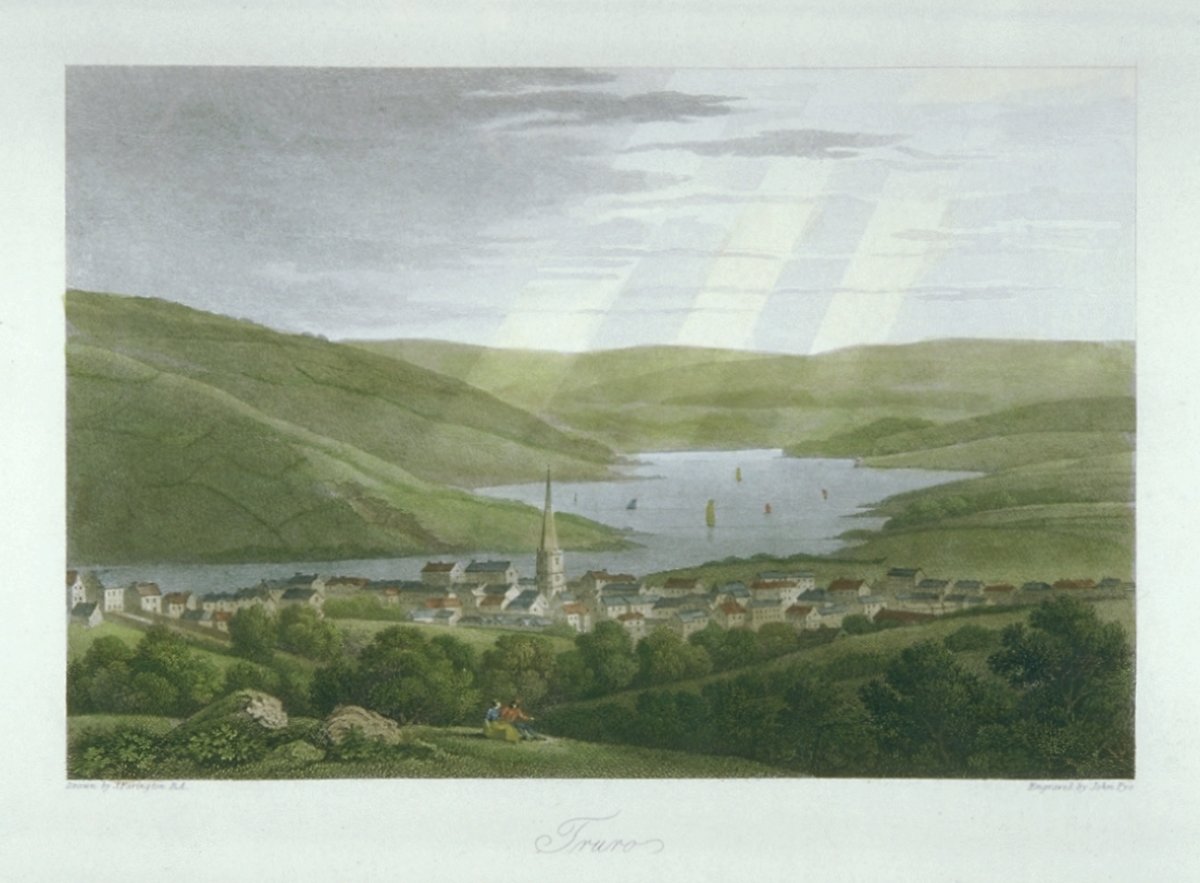

Truro, Cornwall 1813, Joseph Farington (1747-1821), John Pye (Engraver) (1782-1874). Government Art Collection

John Arscott (Ascott) a carpenter from Truro in Cornwall was born and baptised there in 1767. On 18 August 1783 he was tried at Bodmin Assizes on three counts of burglary by breaking and entering the Truro dwelling houses of Phillip Polkinghorn and George Thomas.

He was found guilty of the first charge of burglary by stealing two silver watches valued at 40 shillings from Phillip Polkinghorn. There were a further two charges of burglary at the house of George Thomas by stealing 30lbs of tobacco worth 30 shillings and 15lbs of tobacco worth 15 shillings. He was found guilty of the offence regarding the 30lbs of tobacco but not of the other.

The guilty verdicts led to a sentence of death. This sentence was commuted by the court to seven years transportation to America but by 1785 the destination had been changed to Australia. Between 1782 and 1787 twenty men tried in the Bodmin or Launceston courts were sentenced to transportation.

Many of those destined to be transported were imprisoned for considerable periods of time in local gaols before being confined on prison hulks. John was initially held in Bodmin but was later transferred, probably by being marched in irons as part of a chain gang, to Plymouth. In Plymouth he was confined awaiting transportation on the Dunkirk prison hulk moored on the Hamoaze, the estuary flowing past the Naval dockyard.

The Hamoaze and Dock, Plymouth, Coplestone Warre Bampfylde (1720 – 1791). Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, Exeter.

Catherine Prior (as Catherine Fryer) was convicted at the Lentern Assizes at Exeter in March 1786 of Highway Robbery together with Mary Broad (later Bryant) and Mary Haydon (also known as Shephard). The three young women were committed by the Mayor of Plymouth for trial at Exeter Assizes for robbing Agnes Lakeman on the road in Plymouth in January 1786. The charge recorded in the National Archives was ‘for feloniously assaulting Agnes Lakeman spinster in the King’s Highway feloniously putting her in fear and danger of her Life in the said Highway and feloniously and violently taking from her person and against her will in the said Highway one silk bonnet valued 12d and other goods valued for £1 11s her property’.

All three were condemned to death but at the conclusion of the Assize session their sentences were commuted to imprisonment and they were named amongst those convicts to “be transported beyond the seas accordingly, as soon as may be, for and during the term of seven years respectively”. They were imprisoned in Exeter and transferred to the Dunkirk in Plymouth in September 1786 awaiting transportation.

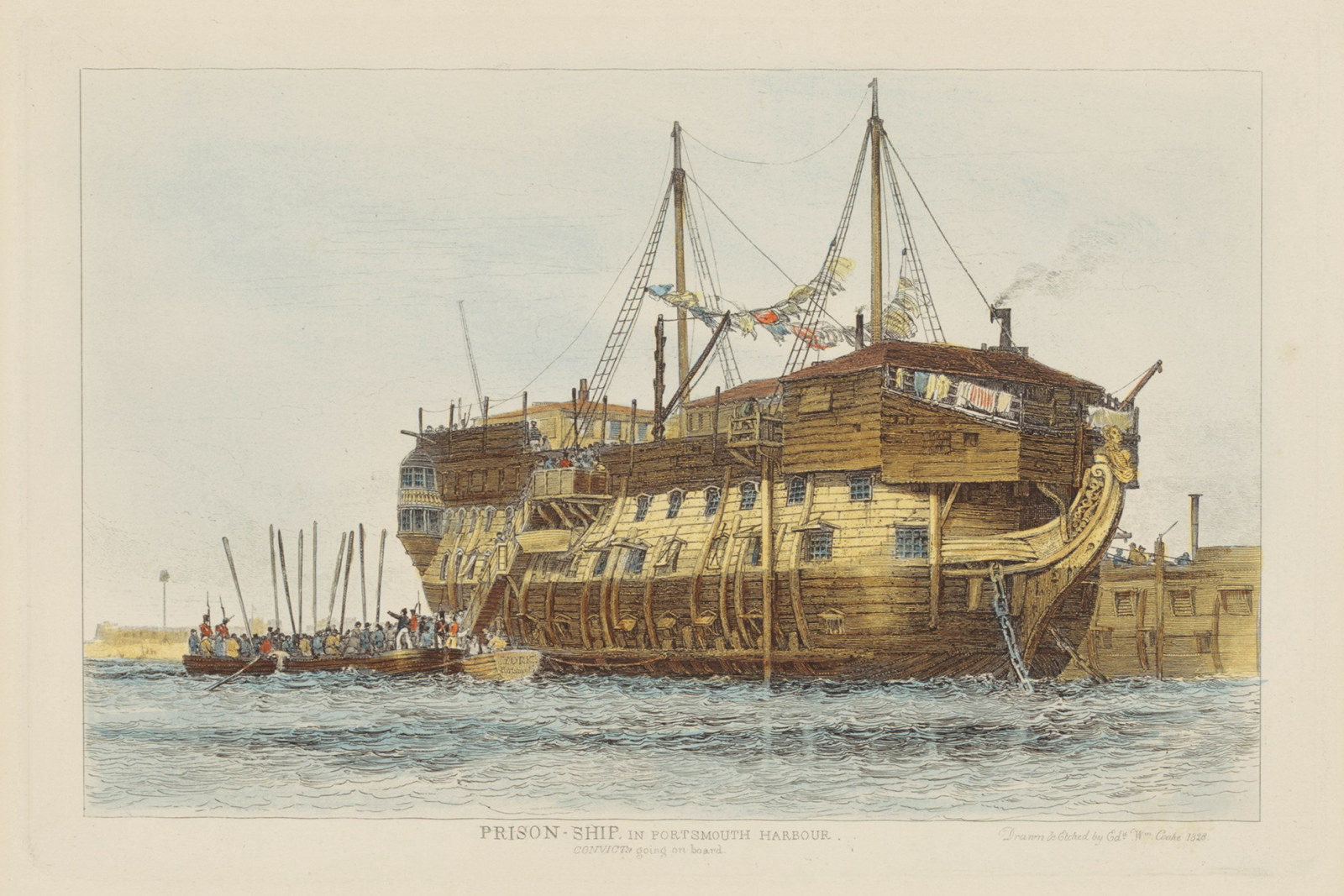

HMS Dunkirk was a floating prison moored in the Tamar at Plymouth. The ship was one of the decommissioned vessels or ‘hulks’ used to provide extra capacity for the overcrowded prison system of the eighteen and nineteenth century. Originally set up in 1776 the scheme was intended as a short-term solution to house prisoners due to be transported but the number of hulks grew rapidly. Managed by private contractors, the hulks were moored initially on the Thames in places such as Deptford and Woolwich, but their use spread to other hulks moored in rivers and estuaries elsewhere such as Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth. What had started as a temporary solution became an established part of the prison system for over eighty years and came to include not only those sentenced to transportation but prisoners in general.

Prison ship in Portsmouth Harbour Loading Prisoners, Edward William Cooke. National Library of Australia.

Dunkirk was built for the Royal Navy in 1754 by Edward Allin at Woolwich Dockyard as a 60 gun fourth-rate ship of the line. The ship was on active service throughout the next years in home waters and in North America, West Africa and the Mediterranean and in 1779 was refitted for service in Plymouth Harbour as a guardship. In 1782 she was decommissioned and sold out of the Navy to became a prison ship in operation in Plymouth from 1784 to 1791.

Dunkirk was used for those sentenced locally to transportation and was one of the collection points for the assembly of convicts for the First Fleet to Australia. The vast majority of prisoners were convicted of theft related crimes with most under thirty five and some children as young as eight. It was the only prison vessel at the time to accommodate women prisoners alongside men and boys and in December 1786 forty one women were recorded as imprisoned on the hulk.

Conditions on all the hulks were harsh both physically and psychologically with overcrowded, cramped and unsanitary accommodation. Discipline and punishment was strict with male prisoners at times being shackled with leg irons and treatment by the guards was sometimes abusive. In 1784 the Superintendant of Dunkirk wrote to the authorities in protest about the treatment and misuse of the women on board by the Marine guards. The result was a Code of Orders issued by the authorities designed to improve the women’s situation. Privacy was minimal, food was rationed and the quality variable and clothing was basic but was provided if needed. The National Archives list the provision of shifts, gowns and aprons for nine women on board Dunkirk in 1784.

John Arscott was one of those confined on Dunkirk probably from its commission in 1784 whilst Catherine Prior and her accomplices were imprisoned there from September 1786. Their sentences of transportation were finally put into place when they were transferred to the First Fleet convict transport ship Charlotte in Plymouth on 11 March 1787.

Governor Arthur Phillip 1786, Francis Wheatley (1747-1801). National Portrait Gallery.

Captain Arthur Phillip RN was appointed by Lord Sydney in September 1786 to command the First Fleet to Botany Bay, to set up the penal colony and to become its first Governor on arrival in New South Wales. A subsidiary settlement was also to be founded on Norfolk Island.

The first task was to assemble a fleet of ships to take over 775 convicts, male and female and over 645 free persons, made up government officials and administrators, marines and their families and naval crews into the largely unknown territory on the other side of the world. Not only would the fleet need to accommodate the numbers involved but would need provisions for the lengthy voyage together with the means of immediate survival on arrival.

It was a huge task but finally a fleet of eleven ships, two from the of Royal Navy and nine chartered merchantmen was gathered. The two Navy ships were HMS Sirius under the command of Commodore Arthur Phillip and his deputy Captain John Hunter and HMS Supply under Lieutenant Lidgbird Ball. There were six convict transports each with an accompanying detachment of marines. Two vessels Alexander and Prince of Wales came from Woolwich, Lady Penryn and the Scarborough from Portsmouth and Friendship and Charlotte from Plymouth. The rest of the Fleet was made up of three supply ships, Borrowdale, Fishburn and Golden Grove. The ships left Portsmouth on 13 May 1787 and the convoy sailed from the Motherbank off Spithead on 31 May 1787.

The Supply Ship Borrowdale 1786 painted from three angles, Francis Holman (1729-1790). Australian National Maritime Museum.

The eleven ships had set sail on “a voyage, which before it was undertaken, the mind hardly dared venture to contemplate”. This was the view of David Collins, Captain of Marines, commissioned to be Judge Advocate in the new colony, who travelled with the Fleet on Sirius. The voyage of over 15,000 miles to settle the penal colony in New South Wales, took eight months with more than 1,500 people on the eleven ships (approximately 750 -780 convicts and 550 others).

Both John Arscott and Catherine Prior sailed from Plymouth on board the transport ship Charlotte to meet up with the convoy at Portsmouth. Charlotte was one of the six convict transport ships and was a 350-ton barque built on the Thames in 1785 for trade with the Baltic. In 1786 the vessel was hired by the British government from the owners Matthew & Co. of London to carry convicts to Australia at a rate of 10s per ton per month.

The vessel was captained by Thomas Gilbert with a crew of 30. The surgeon was John White, designated to be the Surgeon General to the Colony. There were 88 male and 20 female convicts aboard, including Mary Broad and her future husband William Bryant. There was also a detachment of 42 marines of the New South Wales Marine Corps commanded by Captain-Lieutenant Watkin Tench.

After arriving in Portsmouth John Arscott was transferred to the Scarborough another merchant vessel hired as a convict transport. The 430-ton barque was owned by Thomas, George and John Hopper of Scarborough where she was built in 1782 and was captained by John Marshall. The vessel carried 280 male convicts and a detachment of marines and was one of the fastest ships in the fleet.

The convoy left England in good weather and Captain Phillip decided to allow the convicts on deck but when the ships met foul weather during the voyage convicts were confined below decks in the cramped holds.

The fleet sailed first to Tenerife in the Canary Islands where it stopped for a short time before setting out to Rio De Janeiro in South America. The crossing was in hot, humid and stormy weather, water was rationed, and conditions were hard for all especially the convicts. Rio was reached on 5 August and the Fleet remained for a month until 4 September to undertake repairs and maintenance to the ships and to re-supply with provisions. The next leg was to Cape Town, South Africa, where they arrived on 13 October and left 12 November. Here Captain Phillip took the opportunity to replenish supplies and purchased plants and seeds. He also purchased livestock including two bulls, seven cows, sheep, goats and horses all of which had to be accommodated on the ships.

There were seven babies born during the voyage including a daughter for Mary Broad named as Charlotte Spence. Catherine Prior gave birth to her son named John Matthew Prior at sea aboard Charlotte on 14 October as the Fleet was leaving Cape Town. John Arscott now being transported on Scarborough was probably the father of her son.

The Charlotte Medal Engraved by Thomas Barrett in May 1788. National Museum of Australia

The silver medallion depicts the voyage of the transport ship Charlotte. the obverse of the medal shows Charlotte at anchor on arrival in Botany Bay. The reverse is inscribed with a journal of the voyage.

The medal was struck by the convict Thomas Barrett, a forger, transported on Charlotte. It was made at the request of the Surgeon General of the Colony, John White, possibly from a surgeon’s silver kidney dish.

The Fleet now embarked on the final part of the voyage of two months across the Indian Ocean and reached the coast of Australia in mid-January 1788. On approach Captain Phillip divided the Fleet and sailed ahead on Supply with the other three fastest ships, Alexander, Friendship and Scarborough (on which John Arscott was being transported). Supply reached Botany Bay on 18 January with the others arriving the next day. The rest of the Fleet arrived on 20 January. Although Captain Phillip and landing parties disembarked the convicts were all kept aboard the transports.

The First Fleet in Botany Bay 1789, Charles Gore (1729- 1807). State Library of New South Wales

Sir Joseph Banks had advocated the Bay as suitable for the penal colony but Captain Phillip deemed it unsuitable. The anchorage was not good and too open to the Bay, the foreshore was swampy, the soil was poor, and the supply of fresh water was inadequate. On 21January Captain Phillip took an exploration party in three small boats along the coast seeking a better site. Approximately seven miles to the North they found a site, a ria or natural harbour of the Tasman Sea, with excellent anchorage, fresh water and fertile soil which Captain Phillip named as Sydney Cove and decided was the site for the penal colony of Port Jackson.

In Botany Bay the rest of the Fleet was riding out bad weather. Charlotte with Catherine Prior and her fellow convicts on board was blown close to the rocks and collided with Friendship which in turn became entangled with Prince of Wales. Lady Penryn nearly ran aground. This was proof that the anchorage and the area were unsuitable and on 26 January the Fleet cleared Botany Bay and sailed to Sydney Cove with the last of the ships anchored there by 3.00pm.

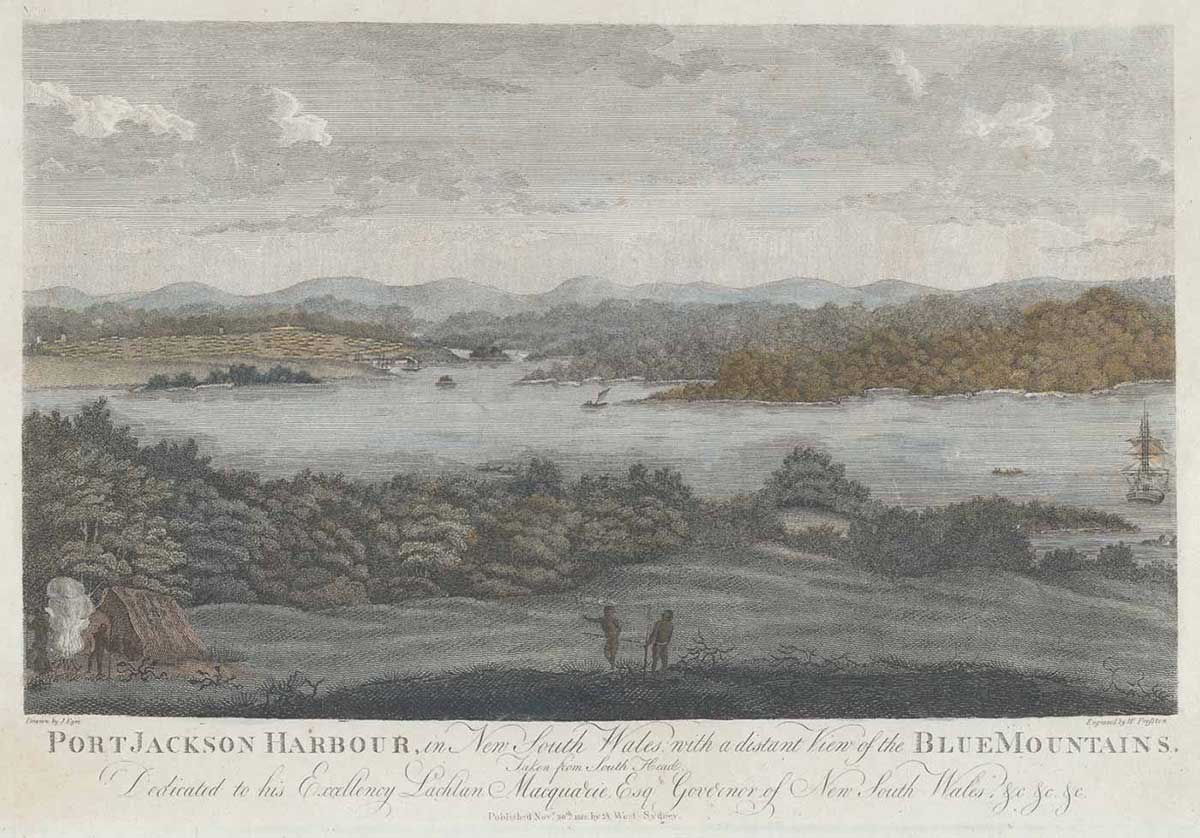

The First Fleet in Port Jackson Harbour, John Eyre (1771-?). National Museum of Australia

On 26 and 27 January an advanced party of officials, marines and a contingent of convicts went ashore to begin the work of establishing the settlement. From the 28 January the male convicts were disembarked from the transports and were put to work. Governor Phillip was closely involved with all aspects of developments. Areas were identified for civilian, military and convict encampments. Tents and rudimentary shelters were erected and by 29 January the Governor’s portable house was in position. Timber was felled, some of the ground was cleared and on 30 January the livestock were unloaded alongside some stores. High priority was given to building strong storehouses.

It was not until 6 February that the female convicts (approximately 180 with their children) were landed. Catherine Prior and her infant son amongst them.

On 7 February the formal proclamation of the colony and Captain Phillip’s governorship was made in a newly constructed assembly ground to all those who had arrived in the First Fleet at Port Jackson. The convicts were not shackled or confined but were guarded by the marines of the New South Wales Marine Corps made up of volunteers from the Plymouth and Portsmouth marine depots.

The work of building the settlement went ahead rapidly with the hard labour of the convict working parties. Although Governor Phillip had urged the authorities to ensure that there was a good representation of fundamental trades and occupations amongst the future population of the colony this had largely been ignored. As a carpenter convicts such as John Arscott would have had his carpentry skills in high demand.

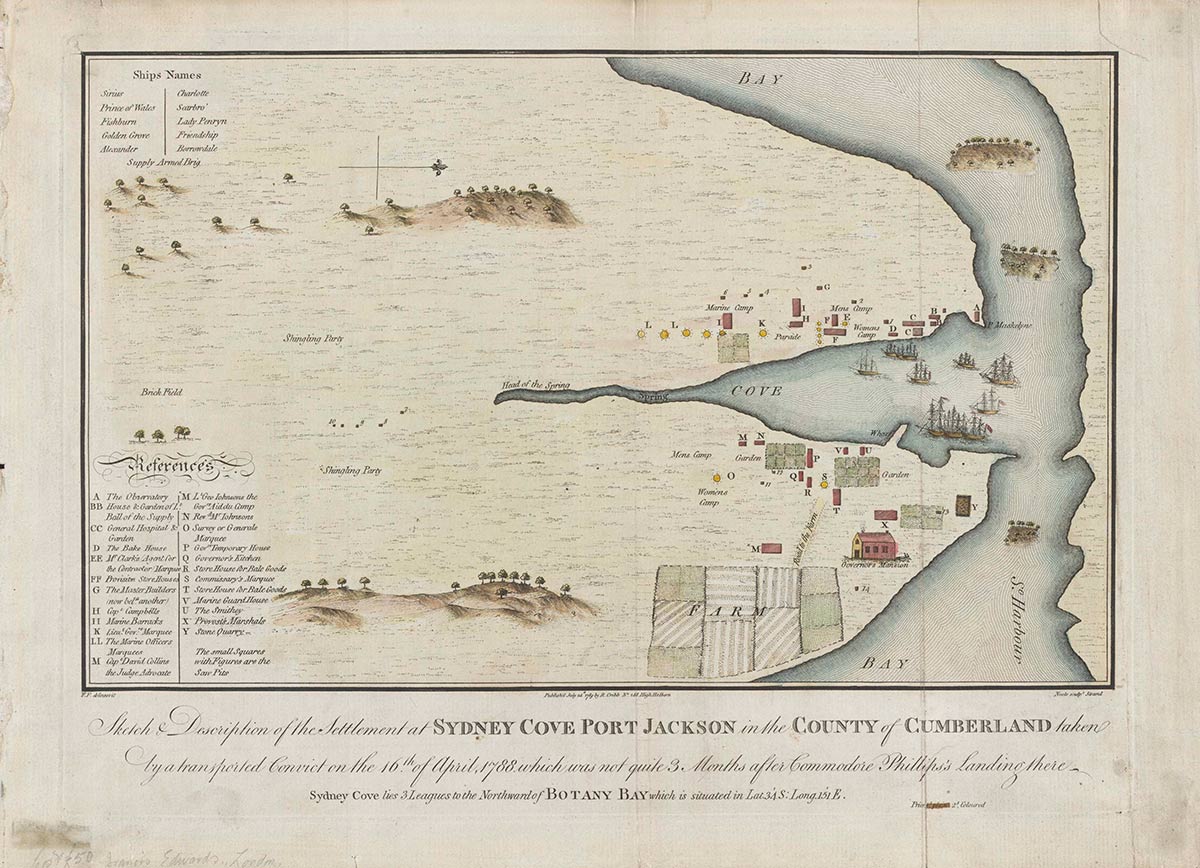

The convicts were initially housed in tented camps for men and for women to the North of the inlet known as the Tank Stream, later huts were constructed. Hospital tents were some of the first erected here. Marine Barracks with marquees for the officers were also in this vicinity together with the parade ground. The Governor’s ‘Mansion’ with the living accommodation for the other officials such as David Collins, the Judge Advocate and the Reverend Richard Johnson, Chaplain to the Colony, were all to the South side of the stream. The settlement also soon included the store houses, a smithy, saw pits, brick fields and an observatory.

The Settlement of Port Jackson 1788, Francis Fowkes. National Museum of Australia

A sketch map drawn by Francis Fowkes, a convict, in April 1788 showing the development of the settlement three months after the Fleet landing. It shows the position of the Governor’s House, the military encampment, the convict tents and the growing infrastructure of the settlement.

The first Services taken by the Reverend Johnson were in the open air and on 10 February he performed ceremonies for the first five convict marriages including for Mary Broad and William Bryant. On the same date he also conducted baptisms and Catherine Prior’s son was christened as John Matthew Prior. Sadly, the Reverend Johnson also carried out his burial a month later.

These were the words of Judge David Collins written in 1798. Although the basic requirements of the settlement were quickly in place the early months and years were difficult. On reaching Australia Governor Phillip and his officials estimated they had only enough supplies to last forty-nine weeks. The rudimentary gardens and farming plots would take time to produce sufficient food and the harsh reality of isolation soon became apparent with starvation a real possibility.

In October 1788 Captain Hunter left Port Jackson in Sirius on a voyage to the Cape of Good Hope for further supplies. The voyage was to be a round trip of seven months and returned with only enough supplies for four months. Rations were cut to under half and then more, fresh produce was scarce and the results of hunting and fishing were meagre. The procurement of food and supplies became a paramount concern to all and the first five years of the colony have been named “the Hungry Years”.

John and Catherine would both have encountered the difficulties of these early years. It was important to maintain morale, order and discipline in the nascent colony in the face of all the challenges of the situation and punishment was swiftly metered out to offenders.

In February 1788 Catherine was accosted near the hospital whilst carrying her baby. Her attacker was Samuel Barsby, a fellow convict, from the transport ship Charlotte, who had a history of violent assault. Catherine sought refuge with Fanny Anderson and her husband Simon Burn (one of the five couples married in February. Marine Sergeant Isaac Knight was called to take Barsby into custody and Barsby was later sentenced to fifty lashes for threatening Catherine.

John as a carpenter was kept busy on building projects, including his own hut, but also built furniture and was a reliable workman. In 1790 he was transferred with other convicts on HMS Sirius to Norfolk Island.

The island was originally settled in March 1788 by a small group of marines, civilians and convicts as an outpost of Port Jackson. The land was fertile and was seen as a farm for supplying Port Jackson with grain and vegetables particularly during the early years. In 1790 HMS Sirius was sent there with more convicts to assist with improving the supply chain to Port Jackson. Unfortunately, the island lacked a good harbour or landing places and when discharging HMS Sirius was blown onto a reef and wrecked. Those on board were all saved but the livestock and the cargo were left on the wreck.

Two convicts volunteered to go out to the wreck to liberate the livestock but found access to the ship’s liquor storage. In a drunken state they set fire to the ship. John braved the surf, put out the fires, ordered the others off the ship, remaining there all night and saving the rest of the wreck and its contents. The loss of HMS Sirius was a blow in maintaining contact with the outside world and for supplying both the communities in Norfolk Island and Port Jackson.

John was praised by Major Robert Ross, Governor of the Island, and on his return to Port Jackson on HMS Supply in May 1791 Governor Phillip rewarded him with a free pardon for his heroism although his seven-year sentence was already completed. In October 1791 he sailed in Atlantic to Calcutta for provisions for the colony and was discharged on his return.

John married Catherine in Port Jackson on 8 December 1792.

Convicts in New Holland (Australia) 1793, Juan Ravenet (1766-1821). Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales

The sketch illustrates clothes, known as ‘slops’ issued to convicts in the penal colony.

Juan Ravenet was an Italian artist who was part of the Spanish Scientific Expedition to Australia and the Pacific under the command of Alessandro Malaspina 1789 -94.

John and Catherine left for England on the Shah Hormuszear in company with the Chesterfield on 24 April 1793. On 3 July John and a small party from both ships went ashore for water and barter with the islanders of Tate Island in the Torres Strait. Captain Hill of the Chesterfield remained with the boat crew whilst Shaw the mate of the Chesterfield and Carter and Arscott from Shah Hormuszear went ashore to meet the islanders. Initially this encounter was friendly but the party was suddenly attacked by the islanders who fled when John fired his musket but leaving Shaw and Carter wounded. With John’s help they were able to struggle to the beach but found that Hill and the boat crew had been slaughtered and that the two ships had been driven off by strong winds. The three survivors took to the boat but were unable to locate the ships and it took the ships three days to work back to the Island. A scouting party went ashore and discovered a lantern and a tinder box, ragged clothing and charred human remains. The original shore party were all presumed dead.

Meanwhile the survivors tried to make for Timor. After days of starvation and dehydration they reached Sarret Island where there was a Dutch Trading Post and they were welcomed by the islanders. John and Shaw were there for seven months although Carter died of fever after four months. In March 1794 they were picked up when the Banda arrived at the Dutch Trading Post and they reached Batavia on 10 October 1794 to learn that the ships had reached Batavia safely.

John also learned that Catherine had died at sea in 1793 two days before the Shah Hormuszear had arrived in Batavia. John then disappears from the records.

Within a decade of the arrival of the First Fleet several first-hand accounts of the founding of the colony had been published providing a valuable and contemporary record for the time and the future.

The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay with an account of the establishment of the colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Published 1789. Arthur Phillip, first Governor of the Colony, from his journals, notes and transactions.

A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay Volume 1 Published 1789. Watkin Tench, Captain-Lieutenant of Marines who travelled in command of the detachment of marines aboard the Transport Charlotte.

A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson Volume 2 Published 1793. Watkin Tench, An account of the early years of the Settlement.

A Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales Published 1790. John White, Surgeon to the Colony, who had travelled on the transport Charlotte.Surgeon White sent specimens of Australian flora and fauna to London for the engraving of the plates.

An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island Published 1793. Captain John Hunter, Deputy to Arthur Phillip and Second Governor of the Colony who had travelled on HMS Sirius.

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales Published 1798. David Collins, Officer of Marines, Judge Advocate of the Colony, travelled on HMS Sirius.

A Plate from John White’s Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales.

The Bartlett Blog is written and produced by the volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk