The Falmouth Packet Service connected Britain to the wider world for over 150 years. Established in 1688 as a vital communications link, these sailing vessels not only carried essential diplomatic correspondence and valuable bullion but also served as transport for a fascinating cross-section of society. This blog explores the remarkable history of the Packet Service, its ships, crews, and some of the diverse passengers who entrusted their journeys to these vessels.

By Linda Batchelor

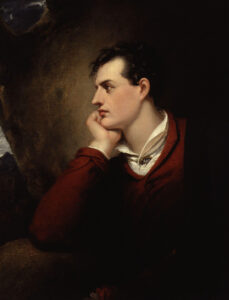

In June 1809 Lord Byron left Falmouth for Lisbon on His Majesty’s Packet ship the Princess Elizabeth under Captain Kidd to begin a tour of the eastern Mediterranean. He chose to record his experience as a passenger in a poem, sent to the Reverend Francis Hodgson, a friend from his youth, which provides a witty, vivid and less than romantic glimpse into packet travel by sea during the nineteenth century.

Lines to Mr Hodgson Written on Board the Lisbon Packet 1809

Huzza! Hodgson, we are going

Our embargo’s off at last,

Favourable breezes blowing

Bend the canvass o’er the mast.

From aloft the signal’s streaming,

Hark! The farewell gun is fired.

Lord Byron 1813. Richard Westall. NPG

Despite Byron’s somewhat jaundiced view that ”I shall not survive the racket of this brutal Lisbon Packet”, the Packet ships, especially those from the major Packet Station of Falmouth, provided a vital link for travellers to Europe and to North and South America as well as a major route of communication between Britain and her overseas territories.

The Packet Service

Falmouth with its deep natural harbour, good shelter and anchorage and easy access to the south-western approaches had been chosen as the major packet station for the Post Office Packet Service in 1688 and remained so until 1851. The Service was a branch of the Royal Mail, established to carry international mails and dispatches by sea in packet ships which were fast, lightly armed sailing vessels. The service made regular sailings to and from Falmouth, initially to Corunna in Spain and then to Lisbon in Portugal. By 1705 there was also a regular service to the West Indies and North and South America.

The packet ships were privately owned vessels hired from their owners by the Post Office. Although initially the vessels were hired from a single contractor the Post Office began to realise the need to spread their risks amongst other ship owners using contracts with standard terms and conditions and from 1785 packet ships were required to conform to a standard design. Whilst the appointment of captains was controlled by the Post Office crews were employed independently by the commanders and owners of the vessels. Large numbers of packet captains had an interest in the ships either as owners or in partnerships and increasingly they became established contractors and major figures in Falmouth life.

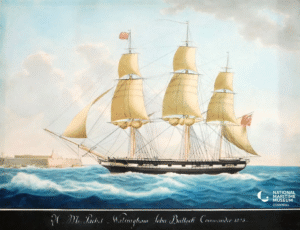

His Majesty’s Packet Walsingham. Nicolas Cammillieri (1773? – 1830). NMMC

Although the major area of operations was the carriage of mails, packets also carried shipments of bullion and a human element of cargo as passengers. Although the service had originally been established to carry international and diplomatic mail between Britain and the continent of Europe the service rapidly expanded to include important commercial and other correspondence and to include destinations outside Europe around the Atlantic rim.

The Carriage of Mails

The integrity of the mails was the uppermost consideration and these ‘packets’ whilst only a small proportion of a ship’s capacity were the most expensive to transport and most carefully protected. Many of the documents, such as official government communiques and instructions, were politically sensitive and others, such as mercantile and business letters, were confidential. Their loss, especially in times of war or unrest, would have led to far reaching consequences.

The documents were packed for transport in custom made leather portmanteaux, the last thing to be brought on board before sailing and the first to be unloaded at the destination. The portmanteaux were stowed where they were easily accessible and in wartime kept on deck so that in danger of loss or from attack they could be instantly jettisoned and sunk.

The Passenger Service

Soon after the inception of the service the Post Office began encouraging the carriage of passengers as a way of subsidising the cost of the mail service by charging the packet contractor ‘head money’ initially set at £4 for each passenger. In 1813 the Post Office recorded income of nearly £10,000 from this source. The major cost of the fares, after overheads, were retained as a lucrative part of the contract and supplement to their income for packet commanders.

Pearce’s Royal Hotel Falmouth. Image: Falmouth Art Gallery

Passengers stayed at hotels such as Wynn’s Hotel (later Pearce’s Royal Hotel) or in one of the many lodging houses awaiting sailing.

International packet travel was relatively expensive, for example in 1703 the cost of the fare from England to the West Indies was £12 and by 1803 the cost was £50. There were two classes of passengers, cabin and steerage and the cost of the fare varied as to the destination to or from Falmouth to the stations in Portugal, Spain or the Mediterranean or to the transatlantic routes of the North America, South America and the islands of the West Indies and the Leeward Islands. In a notice of passengers rates for 1810 it was stated that female servants paid as cabin passengers, children under twelve months were free of charge, children under four years charged as steerage and over four as cabin passengers.

Passengers came from a wide range of official to private travellers. Diplomats and ambassadors with their entourages, government couriers, military personnel, gentlemen and sometimes lady travellers with their servants and merchants and their families. In 1781, for example, the Greville left the West Indies with the Earl of Harrington and a ‘select party’ accompanying him and in 1801 the Marquis de Pombeira and his suite of fifteen person sailed for Lisbon on the Walsingham. In 1774 Captain Lawrance of the Anna Teresa had on board Robert Bogle travelling on business from Falmouth to Grenada and Robert Henson returning to St Vincent from visiting friends in England. In 1776 whilst departure in Falmouth harbour he reported his fellow packet Captain Nichols of the Eagle was impatient to be gone “having on board Sir Rob.t Ainsley Ambassador to the Porte, Captain Yescombe of the King George wrote in 1792 that he was just about to sail “with three and twenty cabin passengers and a King’s messenger for Spain.” Byron travelled on the Lisbon packet in 1809 with a friend, John Cam Hobhouse “muttering fearful curses” and three servants, his valet William Fletcher, Joe Murray and Robert Rushton, “Fletcher! Murray! Bob! Where are you? Stretch’d along the deck like logs”.

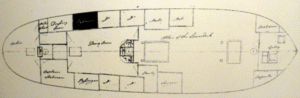

On standard packet ships the cabins were to the rear of the main deck close to the water line. The cabins were lightly timbered hutches without portholes, six feet by four feet, with three either side of the ship each with two berths. There is a replica cabin in the National Maritime Museum Cornwall. In Byron’s poem he mocked its size as “Hey day! Call you that a cabin? Why ‘tis hardly three feet square.” Superior cabin passengers were often given the use of the Captain’s saloon or day cabin which extended across the width of the stern as both a day and night cabin.

There was a passengers mess room area between the individual cabins which served as a day cabin and dining area and where steerage passengers berthed in sleeping cots or hammocks. All passengers except those for Lisbon were expected to provide their own bedding.

Accommodation was often tight on board and conditions could be congested and without many material comforts but many Captains developed good reputations which led to a loyal following amongst travellers.

The lower deck of a standard Packet ship showing the six passenger cabins on either side. Plan of packet ship p.65 The Falmouth Packets 1689-1851 Tony Pawlyn, attributed to Ralph Bird.

Provisions on Lisbon voyages were all found by commanders. As these routes were commanded by senior established captains and the voyage relatively short the provision was good. On the West Indian and American routes provisions were provided on the outward runs only and homeward bound passengers had to lay in their own stock for the voyage.

Accounts of Packet Travel

There are many types of accounts written by passengers, particularly in the form of letters and journals which give an insight into the reality of packet travel. Often passengers conveyed their thoughts in testimonials sometimes individually or together at the end of the voyage. Sometimes it was to express appreciation of the captain, or individuals or the entire crew.

In 1808 after a swift passage of just nineteen days from Halifax the Princess Mary arrived home with a large complement of twenty-four passengers who published their thanks in the following manner,

The passengers arrived in Falmouth, in the packet Princess Mary, from New York, via Halifax, take this method or expressing their joint and cordial thanks to Captain James Harvey (acting) for his gentlemanly and polite treatment on them while on board. They feel a pleasure in this public expression of their high opinion of his conduct and professional abilities. Signed on behalf of the whole passengers.

Lieutenant John Enys writing in 1784 being ordered to join his regiment in Canada, stated in a letter that he had,

Procured a passage on board the Speedy packet under orders for Quebec and was informed by the Agent and ”everyone we spoke to that the Captain (Captain D’Auvergne) was a very agreeable young man.”

The conduct of captains and their crews often drew favourable comments from passengers in relation to dangerous situations or when a packet ship had been under attack from privateers or enemy vessels. This was the case for Captain William Rogers and his crew of the Windsor Castle whose exploits off Barbados led to reportage and comment from passengers and observers and which drew huge public and press attention in England.

In 1807 William Rogers the Sailing Master of the Windsor Castle was in temporary command as captain of the voyage from Falmouth to the Leeward Islands. When off Barbados the packet with a crew of twenty -eight and armed with only eight guns was attacked by the French privateer Le Jeune Richard, a fourteen-gun sloop with a crew of ninety-six men. When the packet crew refused to strike their colours, the French ship ran alongside, grappled with the packet and attempted to board. The packet crew under Rogers resisted with every effort for two and a half hours and eventually boarded and captured the French ship and brought her into British waters.

William Rogers Capturing the Jeune Richard Samuel Drummond ARA NMMC

On arrival home in Falmouth a passenger wrote an account of the engagement which stated “our Captain all the while giving his orders with admirable coolness, and encouraging his men by his speeches and example, that there was no thought of yielding”. Sir Alexander Cochrane, Commander of the Leeward Island Station wrote to the Admiralty to praise the action and the Captain as “such an Instance of Bravery and persevering Courage, combined with great Presence of mind as was scarcely ever exceeded”. Rogers in his own letter reporting the encounter to Sir Alexander, later published in the London Gazette, praised his crew. “It is my duty, to mention to you, Sir, that the crew of the Packet, amounting at first only to twenty-eight Men and Boys, supported me with the greatest Gallantry during the whole of this arduous contest.”

Sometimes accounts of packet voyages and their passengers are also to be found in the logs, journals or diaries kept by those providing the service. Two such records have been transcribed by the Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library, the journal of Captain Edward Lawrance and the diaries of Packet Surgeon James Williamson.

The Journal of Captain Edward Lawrance and the Diaries of Packet Surgeon James Williamson

Captain Lawrance was the commander and owner of the packet ship Anna Teresa. His journal was written during his voyage to the West Indies via Maderia in 1776 as a record of his voyage and account of the islands for his wife at home. He often comments on the persons he met and socialised with and sometimes remarks on passengers sailing between the islands. In Grenada he met “my old passenger Mr Robert Boge Junr, a very good man whom I found to be much esteemed on the Island”. He explains later that he had neglected to describe the island of St Vincent as “paying some Respect to my Passengers took my attention”. He had taken three gentlemen on a passage to Jamaica but was not happy about a lady passenger and her servants “I do not seem well pleased with them. I get rid of them at Jamaica where from my soul I wish they were safely landed.” Unfortunately, he was never to see that as he died at sea off St Vincent a few days later.

Packet Surgeon James Williamson made successive voyages on the Duke of York packet between 1828 and 1835. The voyages were on all the packet routes, except to Lisbon, and included the other Mediterranean stations, North and South America and the West Indies. James was born in Scotland in 1805. He had probably qualified in Edinburgh and entered the Packet Service at twenty- three years old as a recently qualified surgeon in July 1828. As a surgeon he would have been in constant contact with all on board, captain, crew and passengers giving him the opportunity to observe them closely. He kept detailed diaries of his voyages with his impressions of the ports visited, the conditions experienced and often his candid observations on the passengers.

Passengers carried varied in status from dukes and ambassadors and their suites, to merchants, military and naval men, servants and private travellers including two parties of Cornish miners recruited for work in the mines in South America. Many nationalities were represented amongst the passengers most of them men but there were numbers of women and sometimes children on the voyages. All came under James’ critical scrutiny and comment, favourable or otherwise.

The groups of miners attracted attention at several points in the diaries particularly on voyages to Brazil in 1828 and in 1830 to Buenos Ayres. The mines in Latin America were the first to attract the expertise of Cornish miners in numbers in the early nineteenth century. Richard Trevithick had sailed from Penzance in the South Sea whaler Asp in 1816 to go to the silver mines in Peru to consult on mine drainage and this began the trend for British investment in South American mining and the migration of Cornish miners especially to Mexico, Peru, Brazil, Colombia and Chile. In the early years a considerable number of miners left Cornwall from Falmouth for South America aboard packet ships such as the Duke of York.

James encountered a group of miners on his first voyage in 1828 to Brazil. The Duke of York carried the Brazilian Ambassador to the Court of Rome (who occupied the Captain’s quarters) and seventeen cabin passengers (all Portuguese except two). Some were military men, merchants and private travellers such as the Mine Captain Martyn Williams. Mr Williams from Redruth was a young man in his twenties who has offered £200 a year to travel to Brazil to work as a mine captain for a group of miners for the National and Brazilian Mining Association in their gold and silver mines. There were twelve miners (all named in the diary) with him who were travelling steerage. One or two had worked overseas before but the others were leaving Cornwall for the first time. James describes how he and they all encountered the ceremony of ‘crossing the line’ for the first time. Ten of the miners were ‘shaved by Neptune’ and he recorded that “it was really a comical scene to see the various demeanour of those who presented for the operation – some shy and timid- others bold and courageous”. The miners were disembarked at Rio de Janeiro after a voyage of eight weeks and one day with fourteen or fifteen trunks to proceed to their work in the mines and the packet to sail back to Falmouth.

In 1830 James Williamson was on a Duke Of York voyage to Buenos Ayres with another group of miners going to Brazil. The ship was extremely crowded as on board there were a group of two Mine Captains, John Trebilcock and William Jeffery, twenty miners, two females, Mrs Trebilcock with her two children and Mrs Angove joining her miner husband in Brazil. The group was accompanied by eighty large chests which were strewn on the decks. ”I went on board little suspecting a scene of indescribable confusion which awaited me there.” Although the ship sailed on 19 November it was not until the 22nd that it was all stowed away. The miners were going to the Gongo Soco Mine in Brazil’s Minas Gerais Province, 400km North of Rio de Janeiro. James described Captain Trebilcock, who had already worked there for the previous two and a half years as being in demand as “he seemed to be a man who was very clever at his business”. He also noted that the two children Elizabeth and John “by their presence they greatly enhanced our voyage and gave no trouble”. He listed by name and individually described all the miners. He described them as “all wags in their way” and was often impressed with how they behaved. During divine service on board they performed “two or three verses of a psalm well sung by the Miners. This new feature in our public devotion had an extremely pleasing effect”. When the miners left the packet ship and two large boats were required to disembark them and their luggage, although relieved to as to the luggage their presence was missed.

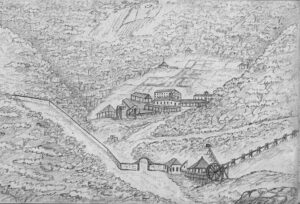

The Gongo Soco Mine Brazil 1839. Sketch by Ernst Hasenclever.

In 1835 the contract on the Duke of Kent came to an end and James Williamson returned to Edinburgh and took up private medical practice in the City. His transcribed diaries eventually came to be a vital and vivid account of the packet voyages and packet passengers.

The End of the Packet Era

After one hundred and fifty years the Packet Service in Falmouth closed. Steam had superseded sail and ports such as Liverpool and Southampton became dominant. In 1851 with the return from Rio of the last operational packets on the station carrying little mail and only a very few passengers the Service ceased. It had made Falmouth a hub of international communication and while it lasted it carried many passengers of all types and to many destinations and provided an insight and a legacy of travel by sea.

For Further reading:

The Falmouth Packets 1689-1851 Tony Pawlyn ISBN 1 85022 175 8

Edward Lawrance Journal – Maritime Views

The Packet Surgeon’s Diaries – Maritime Views

The Bartlett Blog is researched, written and produced by volunteers who staff The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library of National Maritime Museum Cornwall. This blog post was written by Linda Batchelor, a Bartlett Library volunteer.

The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre & Library holds a Collection of over 20,000 volumes and offers access to one of the finest collections of maritime reference books, periodicals and archival material. The Bartlett Blog reflects the diversity of material available in The Bartlett Library.

National Maritime

Museum Cornwall Trust

Discovery Quay

Falmouth Cornwall

TR11 3QY

View Map

See our opening hours

Tel: +44(0)1326 313388

Email: enquiries@nmmc.co.uk