This Royal Charter was granted on 5 October 1661, and marks the transition of the humble village of Smithick (or Smithwick) into the great town of Falmouth.

This Royal Charter was granted on 5 October 1661, and marks the transition of the humble village of Smithick (or Smithwick) into the great town of Falmouth.

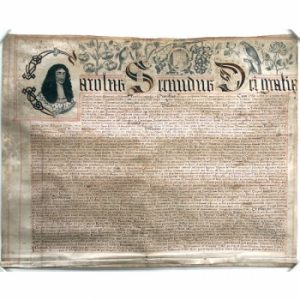

Written in Latin and illustrated with an image of King Charles II, the Charter granted the new town the right to local self-government, and the right to elect a mayor, seven aldermen, 12 burgesses, a recorder and a town clerk. Each of the people appointed to these roles was required to swear an Oath of Obedience, promising loyalty to the monarch, and an Oath of Supremacy (recognising the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church of England). The first mayor, as outlined in the Charter, was ‘our well beloved William Elliot, Gentleman’.

Before the granting of this Charter, Penryn was the chief town in the area. At this time, Falmouth went by the names of Smithick and Penny-come-quick and in its early days was little more than a hamlet with a manor house and a handful of fishermen’s cottages. The name Falmouth was in use as early as the 13th century, but instead referred to the bay and not the hamlet.

The town, as it is today, largely owes its success to the tenacious Killigrew family; wealthy owners of Arwenack Manor. In 1613, residents of nearby Penryn, Helston and Truro petitioned James I to halt Smithick’s rapid progress, fearing too much competition. The Lords charged with deciding its future favoured the Killigrews and the village grew larger despite complaints. The Charter of 1661 made it clear that things had changed, decreeing that:

‘that Village from henceforth shall not be called, named, or known by the name of the Village of Smythwicke, but in all times hereafter shall be called, named, or known by the name of our Town of Falmouth’.

A year later, John Ray visited Falmouth, saying “it is now become a great place…it consists chiefly of alehouses”. The abundance of alehouses noted by Ray is a good indicator of how busy the port had become by the mid-17th century. Even before the arrival of the Post Office Packet Service in 1688, Falmouth was a highly prosperous trading centre with many seamen passing through in need of refreshment.

The Charter was requested by the Killigrews as part of their plan for the expansion of the village, and in 1661, their wish was granted. The document itself refers to Sir Peter Killigrew as ‘our beloved and faithful subject’ and states that it is given:

‘in consideration of the good, faithful, and acceptable services, by him the said Peter as well to Us, as to our most dear Father, the Lord Charles, late king of England (of glorious memory)’

Falmouth – or rather, Smithick – had distinguished itself during the Civil War as a staunchly Royalist area in favour of the king. Pendennis Castle served as the retreat of Prince Charles (later Charles II) in 1642, and of the fleeing Queen Henrietta Maria, who stayed here on her way to France in 1644. Sir Peter Killigrew became known as ‘Peter the Post’ because of the dedicated role he played in communicating messages to Charles I and the exiled Prince. For this loyalty, the family paid a heavy price: when the Parliamentarians attacked Smithick and Pendennis Castle, Arwenack Manor was burnt to a shell.

The Charter wasn’t the only way Charles II chose to show his high regard for Falmouth. Work began on a parish church, The Church of King Charles the Martyr, in 1662, and was finished only 18 months later. Funding for the project came from the king himself, in addition to several other noblemen, as a memorial to the executed Charles I. It is one of only a handful of churches to be dedicated to the monarch.

Falmouth continued to grow; in 1664, 200 houses are recorded here, but by 1750 there were almost 600. In 2011, the town celebrated its 350th anniversary with a variety of different events and exhibitions. Falmouth’s Charter is on display as part of the Falmouth 350 exhibition, Falmouth in the Days of Sail, running until 25 March 2012.

February’s Curator’s Choice has been researched and written by Megan Westley, one of the newest volunteers to join the Curatorial team.